Newsletter May 2025

Les Picaurdières, Crozes-Hermitage

In last month’s newsletter, I wrote about my visit with Vincent Bergeron during my 41-day bender with Remy Giannico, our New York-based gaucho, and this month, three of his 2022 Chenin Blanc wines are arriving. Since tasting them for the first time in bottle last spring with our Los Angeles tastemaker, JD Plotnick (and a couple times out of barrel the previous year), they continue to evolve beautifully. Like many 2022 whites from this area, they show surprising snap and tension for this hot season. I know “hot season” evokes great hesitation, if not terror, for those of us who need that electric charge in our wines. However, as I wrote in more depth last month, 2022s are a different breed—they seem to be Defying the Sun.

Vincent sent some bottles to taste in the early fall of last year. They were head-turning—another convincing 2022 encounter that dismantled assumptions. This resulted in a request to purchase more to bring home, followed by a second order six weeks later. I’ve had more than four bottles each, and all continue to chip away at preconceived notions about how a “hot year” should taste. I also shared a set of his wines over a cassoulet dinner (the last of the season!) with longtime Villa Más sommelier, Núria Lucia Serra. She was surprised that Vincent isn’t on everyone’s radar. (She has since left Villa Más this year and started a new wine bar project in Girona called La Cantina.)

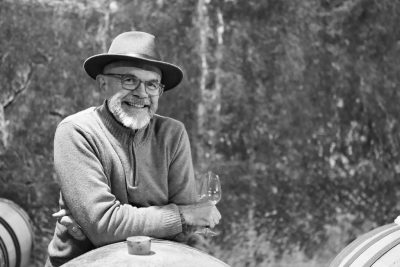

Vincent Bergeron

Don’t sit on your hands. This is an impressive set crafted by a young idealist's gentle but well-worn hands, already showing a deep emotional mastery of his craft. As I’ve mentioned, Vincent is a man whose humility and generosity inspire me to better myself. He’s a gem of a human being. It’s easy for anyone to want to do everything possible to support such a person and bring him the recognition he deserves and needs in the face of financially troubling times. Borrowing from the profile I wrote for our website a few years ago, “Vincent is rare in today’s world of self-aggrandizing young vigneron talents—sometimes appointed by the wine community and often by the self, as ‘rock stars.’” Many seek celebrity and membership in idealist tribes rather than going for truth and an honest view into this métier, this artistic pursuit, this craft–a marriage between Homo sapiens and nature. Vincent is a vigneron’s vigneron, a human’s human, an uncontrived example of how to live and simply let be, spiritually, without trying to be someone.”

Soul-filled? Angelic? These impressions come to mind with Vincent’s wines and the 2022s follow suit. He crafts serious but inviting organic, and, most of the time, no-added-sulfites Montlouis wines. Again, as I put it years ago, “Emotionally piercing, Vincent’s mineral-spring, salty-tear, petrichor Chenin wines flutter and revitalize; a baptism of stardust in his bubbles and stills—a little Bowie, a lot of Bach. His Pinot Noir is earthen en bouche, and aromatically atmospheric, bursting with a fire of bright, forest-foraged berries and wildflowers, and cool, savory herbs rarely found in today’s often overworked, oak-soaked, and now sun-punished Pinot Noirs, the wines that were the heroes of the past millennium, but today are a flower wilting under the relentless sun. Advances in the spiritual heartland of Pinot Noir have been made, though I sure miss the flavors of the Côte d’Or from my earlier years among wine.” Vincent’s Pinot Noir takes me back to the beginning of my love affair with this grape’s propensity to produce the world’s most beguiling and slightly austere red wines. Sadly, Vincent opted out of bottling his 2022 Pinot Noir. Following two gorgeous sans soufre bottlings (the 2020 seemingly made by the hand of Thierry Allemand himself, and the 2021 in the shape of a Montlouis Pinot Noir that could’ve been crafted by Pierre de Benoist), his 2022 fell short of his expectations.

The big tariff we were facing didn’t materialize, so Vincent’s range of 2022 Chenin Blanc wines will be appropriately priced instead of bearing the price of a 1er Cru Meursault. Vincent’s 2022 still whites are some of the first that helped me to recognize the quality of white wine from this vintage across Northern Europe. Again, they’ve got legs and unexpected thrust for a year with such hot weather.

Certain L’Aiment Sec (some like it dry) is yet another wonderful example of clean and finely tuned pét-nat from Vinny. The 2021 was oyster-shell bubbles with taut white-fleshed citric and malic fruits and this 2022 engages a broader range of nuances, dipping into stone-fruit skin notes and is naturally fuller, but only slightly. It comes from 2.6 hectares of various Chenin plots in Montlouis on gentle hills of limestone, clay, sand and silt with an average vine age of 30 years (2023). Its natural fermentation takes place in fiberglass until the finish of malolactic fermentation. Sulfites are added (if they are added at all) after malo, and the wine is aged in bottle on lees for 18 months. No dosage, filtration or fining.

The 2022 version of Matin, Midi et Soir (morning, noon and night) brought the race for first place between Maison Marchandelle to a photo finish. The 2020 version, also from another warm year, was fleshier and rounder, gliding easily on the palate, while this 2022 expresses the same fullness but with much more tension and texture. But 2020 followed a string of hot years that added the extra hydric stress on the vines with a big spring frost that significantly reduced yields, exacerbating the warm season’s influence with even quicker ripening, resulting in many wines with less tension. 2022 followed the cold and wet 2021, which replenished many water reserves. This restorative energy is immediately felt in these wines, and in this early stage of its evolution, I can’t get enough of this MMeS. Though probably not a good post-morning workout refresher, perhaps I would even drink it in the morning, should my mind and body allow such a lifelong regimen while keeping me in top form. More responsibly, it would be perfect for lunch at Costa Brava’s Restaurant Villa Más by the beach of Sant Pol. And dinner, a fitting accompaniment for any inspired cooking, and a solid rescue for a misfire. The grapes come from the same 2.6 hectares of various Chenin plots in Montlouis as the pét-nat. It’s fermented by ambient yeast and aged for 12 months in mostly old 225-400 liter French oak with the first sulfites added after ML. No filtration or fining.

The prized parcel in Vincent’s 2.6-hectare collection of vines is Maison Marchandelle. This Chenin Blanc comes from 0.87 hectares planted in 1970 on perruches, sandstone, and clay. The 2021 was the first year I tasted this bottling, and it inspired the earlier comments about emotion piercing, stardust, and more. Because the 2022 version fights more in the Light Heavyweight class than the tighter, trimmer 2021, it may appeal to a wider audience. It still flaunts all the qualities specific to this site, but they’re slightly more loosely knit with a fuller sensation in the palate and richer in fruit and dried grass aromas compared to the tight weave of 2021. In the cellar, it’s fermented with ambient yeast and aged for 12 months in mostly old 225-400l French oak with the first sulfites added after malolactic. None of Vincent’s wines are fined or filtered.

Stéphane Rousset’s 2023 Crozes-Hermitage “Les Picaudieres” has arrived, and this wine is fabulous, rewinding the phenolic clock to 2015. During that long Remy trip this November and December, I stopped in for a visit. You can read more about that further below in the section titled “Rhône.” Those familiar with it know Les Picaudières is a singular, exceptional vineyard that shouldn’t be overlooked in this vast appellation. It’s Crozes-Hermitage, but it's not what people envision when they think of this appellation and its wines. Just look at the picture.

If there were ever wines to taste on a brisk, sunny June morning at 8:30 a week after bottling, it would be Dutraive’s 2023 wines at cellar temperature. The négociant range was excellent and better than any year since 2016. The domaine wines were superhero level.

2023 is a fabulous effort for Dutraive. I tasted each bottling of their 2023 vintage on separate occasions to get a more comprehensive read on them, as I wanted to see just how much the set was evolving. With just 10 mg/L of added sulfites (up from mostly nothing before 2022), across the range makes them faster-moving targets than wines with more additions. I tasted each cuvée at least three times: once at the cellar in June just after bottling, five months later, and again this spring after eight to nine months post-bottling. I expect a similar reaction from those who knew the wines before the 2017 vintage: smiles, relief, nostalgia. But they aren’t the same. Things have changed quite a bit from the crescendo they hit and stood atop Beaujolais before the arrival of unrelenting heat, prefaced by the calamities of frost, hail and tornadoes. The wines arriving in the US will need some time to regain their land legs before they spring into action.

2022 was a hot season, but following a dreary, wet and markedly inconsistent 2021 growing season, there seemed to be water reserves that kept the wines balanced through the hottest recorded year in European history. The vintage was more concentrated, yet still fresh, and some changes in picking time signaled a return to the fresher profile, but on a much hotter planet.

Jean-Louis’s firstborn, Ophélie, returned home in 2017, a season that marked the start of a series of hot drought years (2017-2020) that tested the region and the willingness of our buyers to jump on the train, even if Dutraive and Beaujolais continued to trend. Dutraive’s more ethereal style with vineyards made of sand made them exceptionally hard to adapt to. During these years, the wines showed much higher alcohol levels and riper fruit profiles, which contrasted with the lower alcohol, brighter profiles of many years before. 2015 was an exceptional anomaly of balanced power, alcohol and acidity. The wines in these hot years differed from the similarly full-throttle years before 2010, celebrated at the time, like 2005 and 2009. The hydric stress of the four hot, low-yielding years from 2017 to 2020 threatened the region’s stability. 2021 was a welcome respite from the heat, but was otherwise an uncontrollable mess across the region. Yet some hit the bullseye with wines that harkened back to the taste profile of 2013.

My initial belief in Dutraive’s medium to long-term wine cellaring credibility came from some old bottles he gifted me when we started working together. One was a 500ml 1995 Fleurie Terroir Champagne, and the other was a 2005 Fleurie Terroir Champagne, bottled in Leroy-like heavy glass, an exceptional experiment hand-bottled from a new oak barrel. The 2005 evolved into a wine similar in profile to a higher-altitude parcel in the “Pearl of the Côte,” and the 1995 seemingly inspired by the hand of the late Jacques Reynaud. They were not only convincing, they were glorious.

Even though 2023 was another hot year following the hottest European year on record, somehow Dutraive’s collection is the closest in spirit to the lighter style of the 2012, '13, '14, and '16 vintages. Though there were challenges with the widely misunderstood '16s, wines in bottle from well-regarded domaines speak of beauty and refinement, including Dutraive’s Fleurie Tous Ensemble (a collection of all the Fleurie plots blended into one) and two négociant Chénas from purchased organic fruit grown by Thillardon. Even the hot 2015, with its higher alcohol and fuller ripeness, had an unexpectedly high natural acidity, making wines that may still be confidently cellared. As I’ve written many times, Jean-Louis says it may be the best year of his career.

My first tastes of the 2023 vintage at the cellar brought me back to my first tasting of their 2013 range ten years ago during my second visit to the domaine, when we were still feeling each other out. I tasted them in the cellar, seated alone with the wines in front of me and the entire family of four towering over me, saying nothing and leaning in with each swirl and sip. I held my cards tight until I couldn’t. A single wine to transcend any Beaujolais I’d ever tasted would’ve been enough. But in 2013, there were five. I didn’t yet have the French words to express everything that went through my head (nor did I have them in English).

In California last summer, I revisited every Dutraive bottling of 2013, ‘14, and ‘16, and two from 2012—about 18 wines with many second and third bottles. I also drank 2009, 2010, 2013, 2014 Foillard Morgon Corclette (my preferred bottling from this domaine), various 2013 and 2014 Lapierre Morgon wines, 2009, 2010, 2012-2014 Alain Michaud Brouilly and Brouilly V.V. (simply stunning, all of them), Chamonard 2009, 2010 and 2012 Morgon. Not a single bottle was “tasted,” per se; rather, they were all enjoyed during many different occasions and were savored to the last drop over many hours of observation, leaving some tiny amounts left in the bottle to check in with the next day. There wasn’t an off wine in the bunch. Dutraive’s renditions stood out as more ethereal and with a softer touch—a signature style of the time from his sandy Fleurie vineyards. It was hard to outmatch that element of his range, but they made up for it in other ways; to compare and define the best is the same as comparing the greatest Côte d’Or producers’ wines from different grand crus. The hierarchy is purely subjective. Each has its optimal moment, and all these wines still seemed youthful—Foillard and Michaud, still babies.

Every Dutraive wine was pristine on its first day open, without exception. Some showed a little squeak and fatigue the next day, with only a few ounces purposely left behind. They were pure nostalgia that brought me back to period inside of about 18 months of endless gatherings to which I could write an entire book with a fabulous cast of wine characters centered around Santa Barbara at that time: Bryan McClintic (who lived in our back room for four years), Raj Parr, Graham Tatomer (lived in the middle room for maybe seven years), Drake Whitcraft, the late California Pinot Noir legend, Burt Williams, and the late winegrower taken from us far too early, Seth Kunin.

Some who share my predilection for brighter, fresher vintages counter that 2013 bettered 2014. There are indeed many extraordinary wines in the former. They’re often tenser, with brighter acidity and higher-toned aromas. Yet the clipped yields and colder season presented challenges that seem to have inhibited some of their prettier aromas from fully expressing, and often delivered shorter length on the palate. However, I can attest that all the 2013s I had from all the growers mentioned were fabulous and as good overall as their 2014s.

Jean-Louis Dutraive, 2016

In 2014, everyone seemed to deliver aromatically open and fabulously balanced wines with long finishes that still don’t show any signs of shutting down—at least from the growers I frequent. I can say there are no wines from any grower in my life within a single vintage that I’ve consumed more than Dutraive’s 2014s, except perhaps the 1999 vintage of Jean-Marie Fourrier inherited as the sommelier at Wine Cask Restaurant in Santa Barbara (with nearly a full pallet allocation before he became famous), purchased by the late Christopher Robles before he went to the supplier side. Dutraive’s 2014s gave me that same intense rush of discovery and obsession as Fourrier’s 1999s. We made an offer from my cellar of Dutraive’s 2014s last year, but few jumped on them, and I understood why. Most newer buyers simply didn’t know this era of Dutraive. They were more familiar with the hotter years and the challenges they presented. I thought about doing a tasting to display their qualities, but I don’t like spreading rare and irreplaceable bottles over fifteen palates. What can you gain from that but a still-life of one moment in the progression of a multidimensional wine that changes from pour to pour, minute to minute, hour to hour? I will sell most of my Côte d’Or wines before I sell another bottle of Dutraive’s 2014s and 2016s. But I’m happy to open them with anyone joining for dinner. The 2023s are the closest relatives since.

Clos de la Grand’Cour

Chiroubles lieu-dit “Javernand” was the juiciest and fullest of the red fruits: thick and voluptuous, seductive, randy. The palate is delicious and a perfect match for the nose. It’s the best example of this bottling from Dutraive I’ve had to date.

Chénas “Les Perelles” usually wasted no time opening up. The earlier tastings showed high-toned candied fruit qualities, and later bottles put on some meaty weight but became fruitier as they opened up. I’ve always been a fan of this wine, and this one is close to the 2016 version.

All three times I tasted the Saint-Amour "Le Clos du Chapitre" it was super classy and elegant—a straight line. Pure, fresh. While it always remains tight for a Dutraive wine, it doesn’t waste time fleshing out after opening. Lots of ferrous, blood, metal, savory flowers rather than sweet. It’s definitely the finest Dutraive wine made from this vineyard.

The Fleurie lieu dit “Les Déduits” may be the trickiest wine in the bunch. Each bottle I tasted started a little closed, with maybe a lean toward a bit of “squeak,” but each time they slowly evolved into a tight, ruby red with striking clarity. This is a wine that cannot be firmly judged in short order.

The 2023 version of Moulin-À-Vent comes from younger vines instead of the ancient ones from the previous years. In the cellar, this was one of my favorites. The color is quite pale, like an old Burgundy. Aromatically spicy and slightly reductive/minerally. It kinda smells like old (but young) Grenache-heavy Châteauneuf-du-Pape with low alcohol—even a little Etna-like. It’s a deep wine, and the palate resonates for a long time. While its color is pale, it’s stout in expression and reminds me of those old Jadot Moulin-à-Vent single parcel wines.

Of all the wines in the range, Fleurie “Chapelle des Bois” has the most Burgundian evolution. That’s to say that it starts with some wood notes (unexpected) that, with more time open, fall away. My tasting note in November: This is more Burgundian, and the acidity and fruit profile say that as much as the woody note. 25 minutes in, the nose is lifting. This can be the sleeper in the range and top billing on any given day. I’m not sure I would ever guess this is Beaujolais over Côte d’Or—trapped somewhere between Vosne and Gevrey—close to Morey. Tannins have a welcome tautness, keeping the richer fruit profile in check. This wine is rockin’. It’s well above expectation, even from Dutraive. It’s awesome. Ask Dutraive for more. It’s classy stuff in my top four of the range.

The Fleurie “Clos de la Grand’Cour” could bring a tear to your eye–the first nose is a real WOW. So classic and refined. It’s like old-school Burgundy without oak—think Mugnier on granite, and the drive in the palate is spectacular. This wine is focused and fine, a dreamscape of a Beaujolais. The balance of stems and fruit is glorious. It has the right balance of bitterness, fruit and acidity. This could be easily missed in the context of others, but should stand tall for those who like it more classic. Also in my top four.

Of all the wines to know Dutraive for each year, my pick is the Fleurie “Clos de la Grand’Cour” and Fleurie “Le Clos.” Taken from the same vineyard, separated by vine age and vinified differently in the cellar, every other wine is a satellite around this center point. There’s a lot of tension here in the 2023 Le Clos, and it takes me back to 2014 in overall style, though a little riper. What a nose! It relentlessly expands and fleshes out over time and has the greatest complexities. Top four.

In the cellar tasting in June, the Fleurie Champagne was the most impressive and pure wine in the bunch. It was bottled a few weeks before my first tasting and was snug in the right way on the palate, but perfumed like crazy. The second and third bottles (November and February) were hard to read, and the fourth bottle in April, nine months after bottling, seemed to head back home. There is promise here, like all the wines Dutraive has bottled under this label, but as Ophélie suggested, we all just need to be patient with it.

The only moment the Brouilly didn’t explode upon first taste was at the cellar, but every bottle since has put it in the running for top billing of the year. The bottle I had in November took a moment, but after thirty minutes it began to climb with brighter and brighter aromas. After an hour, it was fully open, and any doubts were gone with its beauty in full force. It’s the best rendition of this wine I’ve had in any vintage. It may also be the most stable wine in the bunch. This is for those who want a little old-oak Burgundy profile from their Beaujolais. It’s a journey. Don’t drink it fast or you’ll miss its most glorious moments. Top four.

Bubbles are hard for me to assess through tasting. They simply must be drunk—a problem for this organism that’s too easily affected by bubbles: instant bloating, a quick rise of desperation for a twenty-minute nap, and almost a guarantee for a headache the next morning, no matter how much or how little is let in. I need that streak of acidity from the tip of the tongue that scorches all the way down to the epiglottis. It needs to journey to the point of no return. Champagne seems to best reveal the length of its capabilities with the entirety of the eight-centimeter or so journey over the tongue.

Our day in Champagne was our most ambitious, with at least seven hours in a car fully packed with whatever wines we could fit in from Richoux, Bergeron, and Dechannes around the cassoulet pot and 40-day travel bags, the only view being out the windshield and the rearview mirrors. We left Chablis for Les Riceys, an hour east, trudged the clay-rich and rocky limestone vineyards, and tasted Champagne with Élise Dechannes and Éric Collinet, followed by a Van Helsing-intense race against the sunset to reach Montagne de Reims and catch the last rays of light in Pascal Mazet’s vineyards, toured, tasted, and then boomeranged south to Arbois to squeeze in a brief nighttime nap before our 8:30 am start with a new potential grower, and then on to our organic new grower in L’Étoile, Cartaux-Bougaud.

I know no grower as far out on the edge as Élise Dechannes. She’s already all in on organics and biodynamics, but is now committed to completely abandoning sulfur and copper treatments. While other O.B.N. growers are taking all the measures to keep production at a livable level and still losing almost all their crops, she’s at least losing on her terms. She treated the last two harvests with only teas and biodynamic preparations. Nothing was harvested either year.

We were again wowed by Élise’s wines, even if many were opened weeks before and stoppered up in the fridge waiting for us to take their last tastes, leaving the fresh tastes of newly open bottles for her next visitors. She did this with me when I first discovered how great her Rosé bubbles were. The bottle was open for three weeks and only had about three ounces left. It was pure magic. I was shocked. Few other growers do this in our portfolio and still provide convincing results. Peter Veyder-Malberg and Tapada do Chaves also make bulletproof wines when opened young. But more than a decade ago, my only visit ever to Giuseppe Mascarello’s cellar only included bottles on their last tastes that were already open for a month. That set did not deliver, but some of my most exhilarating experiences in the Langhe have come from bottles under this label—and when they’re on, they’re bucket-list wines.

We will once again have a micro-allocation of Dechannes’ Rosé de Riceys, a wine that keeps me up at night, not due to indigestion, but because I can’t stop thinking about it. She’s known more now for her Champagne, but there isn’t a rosé in the world that tickles my fancy more than hers.

Eric Collinet and his vineyards on the right side—the green one

Éric Collinet is a relatively new Source addition and a great friend of Élise. He brought the same three wines to Élise’s that I tasted 18 months prior, and again in May. It was a great exercise in observation, especially with Champagne that had been so recently disgorged before my first tasting. The dosage of these wines takes time to integrate, and a year and a half after my first encounter, they’re quite different—alchemized to fluidity now. He was also organically certified some years before her, and these days he’s planting trees right in the middle of his vineyard rows to encourage greater biodiversity with agroforestry. It must be a swift redirection of conversation for the local non-organic growers in this area when these two crazies roll in for an apero—no treatments at all with one and trees in the rows with the other—indeed, low-hanging fruit for a bunch of backwater chemical Champagne hillbillies. But I’m pleased to say that in one of Europe’s most callously farmed wine regions, we only work with growers with organic certifications. Vincent Charlot and Pascal Ponson aren’t available to us all over the US, including New York, so Remy and I had to sneak in and out like Connery more than Craig. There’s another one en route, too. But I won’t let these cats out of the bag until the litter of kitties are on the boat. I’ve released the news too early and occasionally ended up with litter but no kittens.

Olivier Mazet, from Champagne Pascal Mazet

With the last moments of daylight quickly fading, we met Oliver from Champagne Pascal Mazet in charming Chigny-les-Roses, a village of five hundred inhabitants and one excellent restaurant. Pascal Mazet committed to organic farming when they started, in 1981, and they were eventually certified in 2009. His sons, Olivier and Baptiste, returned to help their quiet, mustachioed, slender and jolly father to contribute to their current offerings. All are released at least seven years after the vintage date, usually nine—a major commitment for these prices on organic Champagne. Leading the charge is the middle son, Olivier, who in 2018 began to incorporate agroforestry by planting trees and shrubs in the middle and ends of vine rows—yep, he’s another crazy, at least perhaps to the neighbors. They’re also exploring more ancient vine-training methods, and soon new labels will be slapped on the bottles. Like almost all of our visits on this trip, it was too short. While we might have been able to make time to dine at that one very nice restaurant, we decided that driving for three hours in a food coma after dinner would’ve been lethal. I thought we might have to eat at Flunch for dinner, but we got an unexpected upgrade instead.

Our day wasn’t only ambitious, it also contained some risks that might’ve made it more exciting. Aside from speeding through France while tasting Champagne all day (and spitting, of course), we still had to get fed and get into our hotel in Arbois.

I opted for KFC for the first time in 23 years, maybe 24. The alternatives at the auto-stop seemed like gambles, not because of the items listed, but simply because they were on the menu at a gas station. At least KFC is like McDonald's (haven’t touched that one in about 27 years), like Motel 6– globally standardized, so you have a pretty good idea of what you’re going to get. The other choices included random animal parts with plenty of sausage in a stew at the buffet, with only the dregs remaining. It would undoubtedly have been dreadful and rewarded us with unwanted consequences. I don’t usually worry about my stomach; it’s the part of my digestive system that has acquired a tolerance for the questionable. But if something barely gets past that first checkpoint, it’s a sign of unnecessary risk on a lengthy road trip. Better off with deep-fried everything from frozen ingredients. This KFC demonstrated that it was a solid emergency lever in France. Never have I thought that I’d go for it, and it turns out I’d do it again.

Arriving late to a French hotel can be like sneaking into your parents’ house in your teenage years in the middle of the night when you’ve forgotten your keys. The desk attendants will let you in, but the disapproving looks can sometimes go well beyond microaggression.

We arrived at our Arbois hotel around midnight, no soul in sight. It was below freezing, and thanks to the Cuissance flowing only fifty meters away, the fog was thick–nearly crystallized, which added to the sting. With no obvious parking spots where we could legally park until at least seven am (moving the car by eight), we stood with a pile of bags in front of a dimly lit entrance, an automated door and an intercom between us and our bedrooms. But the Maison Jeunet’s night auditor let us in without the slightest unpleasantness—it was Jura, after all.

With my second-story window cracked open to let out some of the massive steel radiator’s boiling rage, I snuggled up with the spare pillow and thought about tomorrow and Cartaux-Bougaud. I wondered how Remy would process Sébastien and Sandrine, two of the nicest people one could meet, whose Jura wines won’t stir the depths of your emotional pot, but rather deliver an honest and finely crafted range of organic bubbles, whites, Vin Jaune, Macvin, Pinot Noir, Poulsard, and Trousseau. Many classically-styled, well-made, straightforward wines in the region mirror places like Burgundy, where people generally shy away from stylistic risks. But Jura wines don’t have to be made uniquely for their easily identifiable house style to be deemed more than worthy.

After blasting the heater and patiently waiting for the flailing windshield wipers to scrape the windows clean of the frost, we finally had the first signs of a clear view through the windshield and set off. Our first stop was with a generous man in Poligny whose wines are almost nail-biting in their tension, like watching a gymnast on the balance beam spinning around on the ball of her foot. Some wines are epic. Others nearly throw me off the beam headfirst; his Vin Jaune is simply Simone Biles-level. His whites are quirky but excellent. His reds give me The Twisties. If he just wasn’t so damn controlling about where all his wines go without much intrusion (and this is part of his allure), he might be the most celebrated of all growers in the Jura. Let’s see what happens.

After Poligny, we headed southwest to L’Étoile, caught a glimpse of the mythic Château-Chalon on its limestone perch, and landed at the warehouse of Cartaux-Bougaud. (Back at Champagne Pascal Mazet, we were joined with our good friend, burgeoning winegrower, and our French grower/trouble-shooter, desperately needed with all the goings-on: tariffs, delayed freight, etc. To avoid confusion, I intentionally failed to mention his joining us at Pascal Mazet because his last name is also Mazet, but there is no relation.) On our way to the domaine, Gauthier mentioned we would be having lunch with the family; he kept what it would be close to the vest, but alluded to something special.

The sun broke through the fog here and there, revealing gilded blue relief, but the vineyards and all of Europe were fully in winter’s grasp, and we wouldn’t get warm until we found fire. And find fire we eventually would, but not until after we tasted through their range.

Cartaux-Bougaud’s wines would be a reintroduction for Remy to Jura in their simplest form before the comic book and newspaper cartoon labels took over, and a new style of wines thrust into stratospheric prices. I haven’t yet found an inkling of this domaine trying to rock your world, rather to be accepted as Jura wines of old, though they are crafted to highlight higher-toned aromas and the power of these vines grown mostly in clay-heavy soils. Their reds aren’t richly extracted, nor have they left anything useful to the pomace pile. The whites have broad shoulders, and a deep well rather than an ethereal lift—that’s left for their fabulous bubbles. They’re perfect for local cheese, a fireplace, a warm cabin, hearty food for the laborer, those with scratched, torn, bloodied, and thick hands with an eagle talon grip built for pruning, barrel tossing, and wrenching cellar equipment with the tips of their fingers. Remy got it.

Paul

Generational shifts can go one way or another. Sébastien and Sandrine’s firstborn of three, Paul, is soft spoken and humble with a quiet charisma. It’s easy to see his conviction and understanding of this work and the benefits of more natural production. It will be interesting to see where he further influences the domaine, and I expect him to push things further in the right direction. They began organic culture some years ago, which was a big step. And this is only the beginning.

Fire! At last! It seemed the entire hamlet filed in through the kitchen entrance. It was hard to be quickly herded past their blazing wood-fired oven and into the big dining room with all of their workers, a dozen or more that day. A massive twenty-seat table quickly filled up, faces lighting with anticipation as the blood returned to their extremities. Across from me, Remy silently expressed something between concern and excitement.

We toasted with their Crémant and some Champagne we brought down—I thought they might like to try something other than their wines. And then, potatoes. Lots of potatoes. A series of four or five long, thin silver platters filled with long-cut, slow-roasted, mildly caramelized potatoes were set out with more plates of sausages that closed the gaps on the table. More glances from Remy. I shrugged. Gauthier’s smile grew.

Sandrine entered with smelted edible gold. She set two wooden, pie-shaped containers oozing with magmatic versions of my favorite runny and crusty French cheese, Vacherin Mont d'Or—amber-tinged rind on a fully melted creamy golden fromage. The woman next to me, as charming as she was country rough, her once frozen hands now glowing pink and hot like her swollen cheeks, took a big spoon, quickly subducted the firmer pieces below into the magma and sheered the spruce-aged crust still clinging to the sides.

I was transfixed. Vacherin Mont d’Or, my highest of liquid fromage highs, the pinnacle of what any cheese can express when fully ripened, now quickly forced into a melted state? I’ve had such reverence for this triumph of French cheese. I buy it. Store it. Wait. Hoping, like a bottle of old Michel Lafarge Volnay, that I’ll hit it square on the head of readiness; little margin for error, and when it’s just right, there’re few experiences like it. I never imagined doing such a thing to Mont d’Or, even if it’s been done for centuries. I thought it was regularly done with cheaper, less sophisticated cheeses without a greater purpose, like finding their perfect ripening to compete with the world’s greatest cheeses.

Perhaps my reverence for this cheese in one form is shortsighted. In the US, it’s more expensive and who knows where it’s been and what refrigeration conditions it met along the way. Or, maybe it’s the second-quality milk from old cows already predestined for export. But in Europe, particularly France and Switzerland, and even more particularly, Jura, it’s gotta be the world’s best examples, and it ain’t expensive. I can melt a few each year and not feel guilty about it. I’ve done it twice since. It’s one of the two badder habits I’ve picked up from this trip with Remy. The other? The increased frequency of cassoulet weekends with my new but old traditional Toulouse cassoulet clay pot.

When it was over and the cheese boxes were scraped clean, our stomachs tested, another wave of cheese magma, potatoes and sausage came. Remy’s smile of guilt, pleasure and recklessness was smeared all over his face. I’m sure mine was the same. Nothing else in the world existed at that moment but the pleasure and glory of that moment–I’ll never forget it. It has forever changed my relationship to Mont d’Or: to bake, or not to bake. It really depends on whether my wife is around (don’t bake) or not (yes, bake). If it’s too stinky, bake it. Either way, Vacherin Mont d’Or is a French triumph meant for the world.

Our big night out in sleepy Arbois was at a place seemingly in pursuit of a Michelin star. After our epic lunch, we were tired of eating and drinking and settled on a bottle for the three of us: Poulsard from Bruyère Renard & Houillon Adeline. It was nice to see this celebrated cult Jura wine on a list for a fair price. I think it was 75€. However, its soft pinkish red color was immediately eclipsed by a thick cloud of lees that stifled any purity of the aromas, sadly, and likely, unintendedly, foreshadowed by its label. The wine emerged from the bottle as turbid as pink cotton candy. Behind the thick veil, it was clear; there was excellent juice in there somewhere. But only about two-thirds of the bottle delivered the message; the rest was discardable. I can appreciate growers who want to leave some sediment in the bottle, even if this bottle seemed like a bad rack job or the last bits accidentally taken from the bottom of the vat and bottled before they cut the line. Wines like this, especially when served on home-court in Jura, deserve to be handled with care. I’m doubt the grower bâtons their barrels right before they analyze their wines or barrel taste with clients. In the bottle, they need to be stood upright for a while to clarify before opening. Then they need to be carefully poured. Respected. At least the first glass shouldn’t come out like a violently shaken, nearly empty old glass bottle version of Heinz Ketchup aimed at a ramekin in the service room. Had I paid the going rate somewhere else, which I believe sometimes breaks the four-digit barrier (which I wouldn’t have), I would’ve refused it for lack of careful handling. I don’t know if you feel the same, but I’m fed up with poor wine service, especially when it’s with a bottle that warrants serious attention. If the wine service isn’t done respectfully, what’s the point in committing to anything better than a glass from an already open bottle? At least if you don’t like it, you can quickly dispatch it and move on.

If the winegrowers were present, I’m sure they would’ve been embarrassed; though maybe not if only the last glass partially looked like liquid pink Laffy Taffy. But at the bargain price of 75€, I was ok with a milky first two-thirds.

Through the thick and dangerously eerie fog of the flat Saône Valley, the car’s black ice alert flashing, we left Arbois at seven and headed west to Meursault. It was below freezing for the duration of this unremarkable stretch separating two extraordinary wine regions. We arrived to the cellar of Rodolphe Demougeot as he finished bottling some of his 2023 vintage.

Rodolphe is a giant killer. Built like a pit bull, the man himself looks like he wouldn’t have any challenge dispatching all three of us in short order if provoked. But that’s not him. He’s one of the most unpretentious and gentle growers in the Côte d’Or. Rudy found a seriously new level in 2023, yet another in a sequence of upticks with his modest holdings—modest at least by Côte d’Or standards. What this guy could forge with a bigger stable of superstar appellations and crus? I can only imagine. It doesn’t seem to matter if the year is “classic” or “hot,” he’s bashing it out of the park year to year. There’s so much pleasure with terroir folded into every crease that it’s hard not to stay transfixed in the glass.

We thieved through his 2024s with various blending parts of the wines before sitting to taste the 2023s. I’d never tasted the separate parts of his two lieux-dits, Les Pellans and Les Chaumes, for his Meursault appellation bottling. As expected, the former, just below the premier cru Les Charmes, was richer and rounder, and the latter, high up on the slope, just above Les Perrières, is straighter with finely plucked minerally chords. In his glass-encased winter garden, we tasted the 2023s and did a few blinders. He continues to elevate his game, and his 2023s are no exception. It’s incredible what he achieves in his secondary appellations, like Auxey-Duresses and Monthelie. But in warm years like 2023, these are exactly the appellations that should more confidently strut their stuff.

Three cases of the 2023s showed up at my place a month later, and over the last month, I’ve worked through six bottles. I’ve tried to cut back a little, especially after this nearly abusive trip with Remy, but once you open one of these, it’s hard to stop. It’s been a long time since I sorted an entire bottle alone in a single night (my wife was in Chile at the time), but each glass of his Auxey-Duresses “Les Clous” was far too enticing and the bottle didn’t even make it to midnight.

Short of flash with only two premier crus in his range, he bottles a lot of lieux-dits in his village appellation wines, and there’s distinction in each of those terroirs as much as anywhere. These days, he’s perfectly managing the balance of richer fruit, reduction to keep them closer to the vest at the start, and loads of x-factor. He’s in Côte de Beaune exclusively, but his reds, with three Pommards the highlights, are as lifted as they are rich. The whites are a no-brainer, and his reds are the sleepers.

Skipping Beaujolais altogether, Burgundy straight into the northern Rhône is an abrupt transition. Topographically, geologically and culturally, it’s different. We skipped my usual stop in Beaujolais to visit the Dutraive clan, Anthony Thevenet and the Chardigny boys, all of whom we work with in California and several other markets, but nothing applied to New York. Beaujolais is much more free-wheeling, casual, and sometimes rough compared to Burgundy (though Burgundy is loosening up–well, maybe just a little), and with the river insight of all the appellations, the Northern Rhône is far more rustic and industrial.

If you’re a Northern Rhône grower and it’s your name on the label, your face is probably weathered, hands gnarled, back and neck tight, likely a few ruptured disks and shot knees; you might also have a thick beer-wine-meat belly more like a keg than a six-pack. In Crozes-Hermitage, there’s a lot of easy work down in the vast flat flood plains where tractor blades tear up the land with ease, while more treacherous spots with dizzying heights and steep terraces, like Saint-Joseph, Cornas, Hermitage, and Côte-Rôtie, are weeded by hand, but most often by spray … And then there’s the Crozes-Hermitage vineyards of Stéphane Rousset behind Hermitage. They’re not what most expect. And they’re probably the reason Stéphane’s body isn’t yet broken down and maintains a core closer to a six pack than a keg.

Stéphane was bottling during the only day we had allotted for him, and he didn’t have any time to show us around. I’ve driven through the vineyards enough times, droned them, and mapped them on Google Earth to lead the tour alone through the quietly legendary Les Picaudières and the three vineyards that make up Les Méjeans at the apex of this side in the area around the Rhône, and across the river in Tournon for his Saint-Joseph lieu-dit, Côte des Rivoires. On the latter stop, the road was too precarious for my sedan and Remy didn’t see them but understood the extremity of their cliff-like position.

Almost every vineyard in Stéphane’s collection is the hardest of hard vineyard work to be found in France. The only area for tractor work is down by the river on loess terraces, mostly used for his white wines and the entry-level Crozes-Hermitage, and on two parcels of Les Méjeans on the top plateau. Everything else is done by the four hands of Stéphane and his father, Robert, on the Pangean remnants carved into various terraces of granite and sometimes metamorphic rock. In the case of Les Picaudières—a sort of transitional material between igneous and metamorphic—it’s a geologically complex and intimidating slope that stands alone on its steep face.

Stéphane’s wife, Isabelle, tasted us through the new releases, and it all made clear sense to Remy: Rousset’s Crozes-Hermitage wines were anything but ordinary from this, perhaps the most ordinary of the Northern Rhône appellations. They were the true underdogs of Crozes-Hermitage, given the quality of their terroirs. They’re more southern Saint-Joseph granite or the extremity of Hermitage’s Les Bessards—little in common with the Crozes-Hermitage of the flats that make up about 75% of vineyard surface area and probably quite a bit more in overall production. Crozes-Hermitage from these granitic parts is rare.

The financial incentive is low for Crozes-Hermitage growers because of its appellation price cap. This means that if you can’t do the work by tractor, you’re going to struggle to find people to do the work. Labor costs have to be managed, and sometimes they’re running lean on willing hands. If you were a harvester who didn’t care about the quality of the grapes you picked, would you opt for long days on hot terraces over the flats? Maybe it’d be romantic for a few years, but that romance might run dry pretty quickly. In the hotter years, Rousset can get caught off balance and can’t pick the fruit fast enough. This can lead some wines to express the sun’s abuses. But when the season is milder and not a bum-rush harvest, the whole range is tight. The 2022s were rock solid, but sadly, almost already sold out by the time we tasted them.

Outside in the cold and darkness, with faces backlit by the warehouse lights further in with bottling in full clank and buzz, I finally met Robert. I’d only seen him in pictures. He was a beast of a man when young, seemingly double the size of his stout but average height son, Stéphane. Of course, today he’s more squat but still a massive frame with strong hands, more like skillets, and with medium-sized potatoes for fingers. Our encounter was brief, and he was much nicer and more welcoming than I expected; I guess I’d forgotten that giants are often gentle, too. He’s also a giant in my personal wine story with the Roussets and their nearly forgotten celebrated vineyards on some of the region’s historic terroirs. The other parts of Crozes-Hermitage to the south of Hermitage shouldn’t be part of this appellation but a different one altogether. It’s much closer to the top sites of the entire region, while the others are relatable by climate, grape and culture, but not much else. While we find the Roussets the financial incentive to see how far they can take it, let’s continue to enjoy their wines that offer the greatest value for serious wines in the entire Northern Rhône.

Photo of a photo: Robert and Stéphane Rousset

France overflows with hidden gems in the world of food, art and craft. Just down the street from about any friend’s house, from the Loire Valley to Provence, there are always some fabulous multigenerational artisan cheesemakers, bakers, charcuterie masters, a gypsy truffle hunter with great prices you have to work a little for, and broke artists on every block. It’s harder to find these gems unknown to the wine world now with importers scouring every corner, but we’ve got one, and he’s hard to top in quality and price with his Syrah.

Just outside the southern border of Crozes-Hermitage, lies Domaine des Collines, a winery with exceptionally high-quality wines at an incredibly affordable price. It’s run by Sébastien Mazérat, one of the most mechanically ingenious winegrowers I’ve ever met. We were greeted with warmth and openness on this drizzly, cold day, and a smile and laugh of a man who clearly loves his life. Mid-forties, Sébastien is a longtime friend of Gauthier, so our warm welcome was already a little expected.

Another Working Class Hero, I’m sure that if Sebastien were given the opportunity with a slab of Cornas, he’d be on the podium. Here we’re talking wines that will hit retail shelves under $20 and easily put many neighboring high-quality Crozes-Hermitage growers on notice, if they even knew he existed. A native of Cornas and from a family of winegrowers, after nearly a decade in Chapoutier’s cellar, he’s now in Rhône no-man’s land producing wines in the style of the luminaries of those celebrated hillsides.

Not only talented in the cellar, he’s da Vinci-like in his creative mechanical ingenuity. Because he can’t get much for his wines in the broad IGP Collines Rhodanienne, he needs to keep his labor costs down, so everything is farmed and picked by machine—machines he bought and adapted to his specific need in the vineyards. We were given a tour of his gadgets as well as his wines. If he wants a certain kind of filtration, he designs prototypes that, when other growers learn about them, they ask him to make for them too. Custom fittings for all his tanks, labeling contraptions, dolly case-loading assistants, everything is a custom contraption. He’s a talented inventor who also has a great palate for wine. Every little detail is optimized in efficacy so he can do as much as possible alone, and this carries over into everything he produces. His two versions of Syrah, one with a soft addition of sulfites and one without, are stiff competition. They need to be tasted alone, away from other organic Syrahs, because few could challenge this one for the price. It’s just not a great value; it’s a great wine for an absurdly low price. If I told you the price was double, you wouldn’t blink. You’d likely even think it’s still a great deal.

After an unexpectedly fabulous multi-course lunch cooked over fire by a friend of Sébastien (by far the best I’ve ever had in these parts, which is usually of the belly-thickening vigneron type), Remy and I headed south.

It was a two-hour drive, which gave us just enough time to reflect on the three-week French leg of our trip. We agreed that the cassoulet back at Laurent’s in Cahors and the Cartaux-Bougaud madness of melted golden mountain cheese on roasted potatoes and the multi-course lunch we just wolfed were the top meals in France. I also had to acknowledge the KFC emergency rations from two nights before. It wasn’t the worst meal I’ve ever had—not even close. I don’t remember Remy’s reaction to this admission. It was probably silence.

Still dumbfounded by Sébastien and his extraordinary wines that go for nearly nothing, Remy said, “How do we show Sebastien’s Syrah next to other wines? They’re such a gift.”

“We don’t,” I replied. “It should go alone.”

We were on our way to my regular French refuge, my French home away from home, La Fabrique. Sonya was waiting there with boudin and sautéed apples and upside-down pineapple cake finished with rum. It would be Remy’s first time, and it wouldn’t be fair to include her meals in the competition; they’re in a league of their own. Some people I’ve taken to Fabrique don’t appreciate it like I do, and I understand—it’s not for everyone. Sonya says that I belong to the house now—and she’s right—but she wants to sell it because it’s too big for her and she’s too old now to take care of it alone after the passing of her husband, Pierre, last year. But Fabrique is not only a place she could make into an amazing home–a home is a state of mind. Somewhere to forget the world while sojourning there, eat like it was post-WWII Provence, inhale a little second-hand smoke, and drink things you normally wouldn’t. I knew it would be a Remy place.

Next month