I was jolted awake in the morning by a banging on the iron gate of my ancient Airbnb, followed by more knocks on the front door. I got out of bed in just my boxer briefs and immediately saw three police officers in black fatigues just outside the window on the tiny porch. One glanced over at me, and I stood there exposed and stunned, my pre-coffee brain failing to process what I was seeing for an instant before I dodged to the side and out of sight. I fumbled to pull my pants on, hopped on one foot as I tried to get my second leg in, slid into a T-shirt, opened the door and blinked at them in confusion.

They politely yet tersely informed me that the spot where the owner of the Airbnb told me to park actually belonged to a local resident and I had to move the white wagon or I would be towed. My weak protests got me nowhere and I stumbled out to the car and drove from the fortress, down to a public lot at the bottom of the hill. Then I marched back up under a dark cloud full of assorted keyboard epithet symbols as I cooked up a scathing review that I knew I’d never be able to get Ted to write about the Airbnb host.

I checked my phone when I got back and noticed that I had forgotten to set my alarm the night before and the police had actually awakened me at exactly the time I would have set if I’d remembered. I had just enough time to make some breakfast before heading back to Nico’s house. And just like that, annoyance turned to gratitude toward those lovely members of the gendarmerie.

The day before, we had stopped at a convenience store where I bought some eggs, so farm fresh that they were covered with feathers and specks of what I hoped was dirt. This would never fly in the states and my cynical brain had me convinced that it was done purely for effect in France, a rural marketing tool. I scrambled some, brewed coffee from the pods the host provided (so generous, so thoughtful), and vacuumed it all up.

I got to Nico’s place right after they had all finished breakfast. Leticia asked me if I’d like some cereal as she pointed at a wide selection of colorful boxes. I said I’d just eaten some eggs and both she and Nico shot me a strange look. Ted commented on my determination to eat them for breakfast every day and I was surprised to learn that this was unusual over there; they’re actually more likely to eat them for lunch or even dinner. I did take her up on a coffee though, and drank it down in one gulp so we could get back on the road.

After goodbyes, hugs, handshakes and promises to see each other again in just a few days, we jumped into the white wagon and headed west for Côte-Rôtie, to meet with a big name in that region. He was a bit of a celebrity and a hard man to connect with, so Nico was going to pull some strings to get Ted in the door. But first things first: we had a midday meeting set with someone from the other end of the spectrum, a man who was officially the smallest producer in Côte-Rôtie.

We passed through Vienne, a picturesque city of new buildings and old, as well as many crumbling with antiquity. Every style seemed to adhere to the beige limestone and terra cotta rooftop construction of so many towns we’d passed through, with a few ancient church spires and castle turrets in the distance. The flat and green Rhône river drifted imperceptibly beside us, placid as a long thin lake.

Just a couple miles south, we entered the commune of Ampuis. The road took us along the base of the steep Côte Brune hills, where vineyards stretching into the horizon grow at angles as steep as forty-five degrees. Côte-Rôtie is split up into two sections according to soil type: the Brune (brown) hills are chock full of iron-rich schist, while its sister hill, Côte Blonde, is pale in some parts with granitic soil, also mixed with schist. The sharp angles preclude the use of machines and must all be worked by hand. In the blinding hot sun of that day, I was daunted by the idea of pruning and picking under that relentless exposure.

We entered the small town of Condrieu, a wash of peach, beige and gray stone and concrete, like a pale sun-bleached Mediterranean village. As we weaved through its narrow streets and alleys, we jockeyed with other swerving drivers for a parking spot; there was a farmers market in a small town square nearby, so it got a little cutthroat and took a while. Once on foot, we strolled down the narrow, shop-lined, cobblestone walkways, grateful for the coolness of the shade. The appointment prior to the later mission with Big Name was in a small courtyard of ivy-covered walls, and ancient wooden doors with old iron fittings marked the spot: the cave of Pierre Bénétière.

Inside was a minimally illuminated cellar with splotchy concrete and old stone walls and a low brick ceiling. A gravel-covered floor crunched loudly under our feet. Bénétière has a reputation for being a bit of a recluse and other rumors even painted him as taciturn and distant, so we proceeded with caution. Ted warned us not to take too many photos, like the vigneron was some sort of wild animal that might scare easily, or take quick offense like a primadonna.

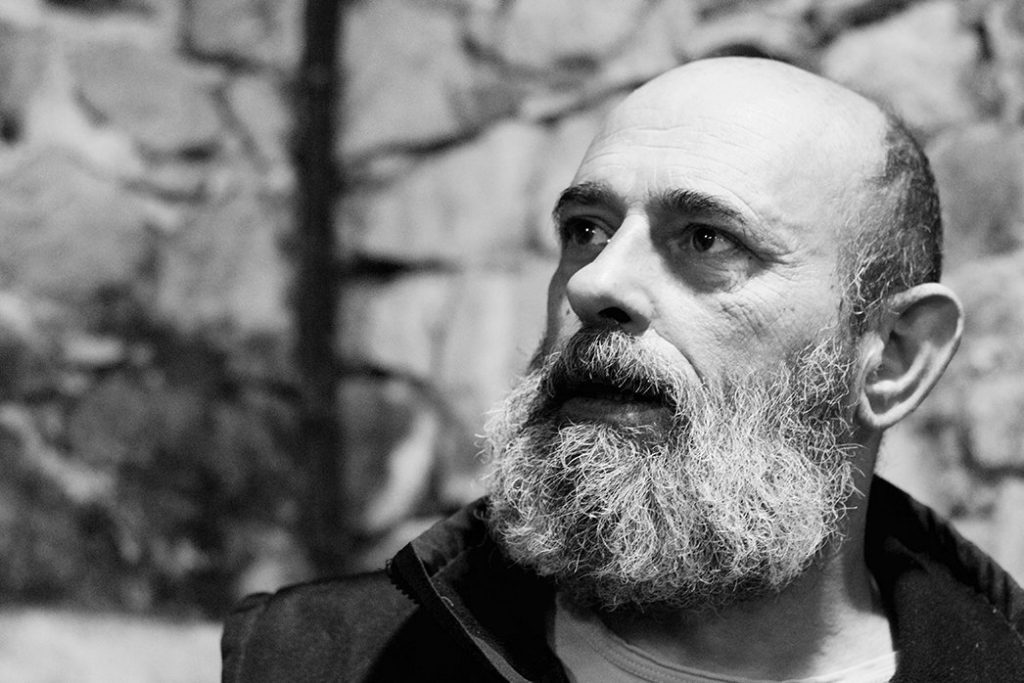

Pierre greeted each of us with a warm handshake, intense eye contact and a glimmer of amusement twinkling in his eyes. He has a long, broad gray beard that blends in with the gray U of hair circling his shiny, tan pate and but for his gray jeans and the thermal vest over his t-shirt that day, he definitely resembled some fictional version of a hermit. He spoke nearly perfect English, yet still excused himself for his lack of proficiency—I got the distinct impression that while his accent was spot on, his vocabulary was a little limited or rusty.

Ted immediately let him off the hook with his solid French. Then he found out Andrea was from Chile and started speaking fluent Spanish with her, something that came easily since his wife was from Spain. Maybe because of this, he showed absolutely no objection to her taking as many photos as she liked, so she clicked away. I might have just been imagining that he shot me a quick look of dismay when I snuck one, like I was still limited by that early warning from Ted and it just seemed that Andrea’s Spanish garnered her favoritism.

Where was the cranky loner? This guy was charming, witty and friendly in the shoot you a grin as he gives you the side-eye sort of way. I began to think that the early reports of his behavior were the result of visits on off days, or maybe he just didn’t like those visitors that much.

He handed us glasses and got his long glass pipette, started pulling from the aging barrels, and treated us to tastes. The wines were big and earthy, young and blunt, with obvious promise. We sipped and swished, then followed his lead by spitting right onto the gravel floor.

He and Ted talked about some missed communications, some email or other that had gone without a response. Pierre admitted that he wasn’t much for correspondence or social media; in fact, he doesn’t even have a website for his business. Ted told me that two years earlier he had promised a few cases of wine to The Source, but never fulfilled the order. Then Jérôme Brenot, from La Grenouille Selections and the point of contact for Bénétière, made a second visit again a couple years later and the order was still sitting there in the corner of the dock. On this day, Pierre quickly made promises to Ted that he would get those cases going, along with some from the new vintages.

All of this made it clear that what people mistook for reclusion and evasiveness was really a case of frustrating yet comical disorganization. And to be clear: he has no interest in changing and he doesn’t need to, because his wines are extraordinary; he’s like the absentminded genius who accomplishes great things but at the end of the day can’t find his car in the parking lot. His assistant ducked in to relay a message, and when he left, Pierre informed us with a wink that we had just met his Paduan. (For those who don’t know, a Paduan is a Jedi student learning under a master in the Star Wars movie franchise.) I’m a movie buff and this man was speaking my language.

He took us over to where a few of his bottles stood in line on an upended barrel in the corner. Andrea, Ted and I gathered around as he popped corks and poured. He asked Ted if anyone ever told him he looked like Jude Law. Ted shrugged and said, “maybe?” Then Pierre turned to me and asked if I was from Ireland and said, “You Irish… A bit crazy, all of you, yes?” I responded that no, I was American, but he smile-frowned like he didn’t believe me. At any rate, my heritage is written all over my face and hair, so how could I argue?

Pierre told us that his parents were wine merchants who sold to local businesses, and he was the first in his family to go to enology school and make his own wine from land that he bought, tore up and replanted himself in the 1980s. He produces three wines from two holdings in Côte-Rôtie and one from just to the south in Condrieu. His Cordeloux label comes from the granitic soils of Côte Blonde, while his Dolium comes from Côte Brune and is only available in the best of years, when it yields only two barrels. His Condrieu comes from less than two hectares from Le Riollement, above the famous Château Grillet. They were all miles away, so there was no time to jump into a car and tour them like Ted likes to do (and I could see his wheels turning as he tried to figure out how we might fit it in), so Pierre grabbed a beat up and dirty plastic topographical map from where it leaned against the wall and pointed out each location like a geography teacher.

As we tasted, Ted raved that the 2015 Côte Brune was “floral and earthy, savory but not too salty and not sweet.” Pierre uses SO2, but the wines show clear signs of an otherwise natural process. He’s one of the few producers who use the stems, and Ted said they express “a sleek, elegant and spare quality that shows no signs of the superficial power that comes with too much fertilization of the soil.”

Ted waxed on: we were “drinking the iron in the soil and the toil of the people.” There were “exotic tastes like green and blue notes, spice with juniper and lavender and a bit of pepper.” When we all brought up how well the wine would pair with food and Ted mentioned the great dairy in the region, Pierre offhandedly responded, “I’ll start drinking milk when cows start eating grapes.” Ted then complimented him on his simple labels and Pierre said, “yeah, they’re not like the other guys’, who seem to be selling shampoo.”

With no time spent in his vineyards, the trip was the shortest one so far. I know I’m not just speaking for myself when I say that I wished it could have been longer. “Like his wines, he isn’t flamboyant, but he’s fun and smart, earnest, with a playful side,” Ted said. He’s fond of finding parallels between the makers and their products and he vowed to go back and just hang out with him at some point.

I shook Pierre’s hand as we left and there he was again with that intense eye contact. He said, “you’ve got to look someone in the eye to tell who they really are.” I heartily agreed and he squinted at me sideways, shook his finger and said, “Irish,” as if that somehow summed me up in a nutshell. I laughed and conceded the point.

Later we would go on to meet the famous Big Maker in the region, which turned out to be a comedy of errors and a bit of a letdown, especially after the pleasant surprise that was our encounter with Pierre Bénétière. But that’s a story for another time…

Next: A Breather in the Magical Land of La Fabrique