Welcome to the June club, which features three wines from three producers. The wines have many differences, but, more crucially, they have a few things in common. This month’s exploration is perhaps a bit less technical than in past clubs, but it’s no less interesting. Best of all, the wines are delightful.

Actually, “delightful” may be too limiting, perhaps depriving these wines of some depth and gravitas. While no one would characterize them as “monumental” or “colossal,” their intricacies perhaps exceed “delightful.” This is all indicative of the contortions we often find ourselves in when contemplating this month’s theme, Pinot Noir.

A grape that defies easy categorization, can produce a dizzying multitude of styles, and boasts a genome more complex than our own, Pinot Noir eludes characterization when it produces even simple wines. The beauty of its greater wines, rather, lies in their ability to integrate seemingly opposite forces: structure and suppleness, depth and buoyancy, gravity and delight. This month’s wines straddle that divide. More specifically, we’re drinking three Pinot Noirs from cool-climates. Technically all great Pinot regions are cool, but the ones featured today are outside the epicenter of the Pinot world, the Côte d’Or. They’re satellite areas or neighboring regions lacking the Côte d’Or’s perfect Pinot conditions. Today, attention is warranted for these lesser known Pinot zones, which have for centuries been afterthoughts, because, in the era of climate change, they may soon have more to say. So, on to the wines (in no particular order).

First up, Sancerre. Sancerre? you ask, incredulously. Yes, indeed. The world rightfully looks at Sancerre as the home of Sauvignon Blanc, but there is red wine here too, made from Pinot Noir. Wine labels declare it Sancerre Rouge, showing subordinate status (no one bothers to label the whites Sancerre Blanc). For the most part, Sancerre Rouge these days is regarded as a simple, insignificant, often underripe or light red, with little character—classic lunch wine. It wasn’t always this way. Before the phylloxera plague of the late 19th century destroyed Europe’s vines, Sancerre was primarily planted to Pinot Noir, its wines enjoyed at the finest tables on both sides of the Channel. In the post-devastation aftermath, during replanting, landowners discovered it challenging to graft Pinot Noir to the phylloxera-resistant American rootstock, so they converted almost entirely to Sauvignon Blanc, which took the grafts much more rapidly. To shift a region’s entire identity overnight is almost unthinkable today, but such were the exigencies of the time.

As a Pinot place, we can’t help but regard Sancerre in relation to Burgundy. Many producers here do too. They’re the first to point out that, located on the Loire Valley’s eastern edge, Sancerre is closer to Beaune than to Angers. The climate here is different than Burgundy. It’s cooler…and warmer. That is, the diurnal shift in Sancerre is greater than temperate Burgundy, resulting in a more jangly wine that ripens under greater highs, but respirates in chillier nighttime lows. More stark are the soil differences. Burgundy has many soil types, but all based on variations of the perfect mixture of clay and limestone. Sancerre’s soils are more extreme and specific. Kimmeridgian limestone marl dominates the landscape, but there’s also chalky caillottes (little stones), and silex (flint). In addition, there are good amounts of clay in some parts and iron-rich red soils, as well.

The bottle you have before you is François Crochet’s Sancerre Rouge 2014. Most of François’ Pinot lies on caillottes with some on the reddish clay soils. It’s a good mix, because Pinot Noir on pure limestone will lack body and become too strident. Too much iron-rich clay, on the other hand, will produce a wine that lacks lift and finesse. As you may know from the precision of his Sancerre (blanc), François is an incredibly meticulous winemaker, and this Pinot Noir evinces the same dedication. It boasts the ripeness of 2014 and density from low yields with tightly executed extraction. Clearly, François cares about his Pinot Noir because he’s raised it in a non-oxidative style that suggests he’d like to see it grow old. It drinks well now with dark cherry flavors, a brace of earthy, soil flavors, and a fine-knit floral array. That hint of toast or char probably comes from a touch of reduction, which may well blow off if you open it or even decant it for a little while before drinking, though to us, it’s great straight out of the bottle.

Our next bottle, the 2013 Dominique Gruhier, comes from the unheralded/unknown appellation of Epineuil. The name is harder to pronounce than the village is to find, as it sits just about 20 minutes northeast of Chablis, outside the town of Tonnerre. It’s a cold place with classic Kimmeridgian soils. Epineuil’s greatest vineyard area lies on a massive and steep slope, the Côte de Grisey, where Dominique has most of his vines. The Côte is richest in its center where a bulge of clay graciously delivers to these wines their perfect mid-palates. While in times past, a celebrated site for Chardonnay, the Côte de Grisey is able to ripen Pinot Noir because its chilly, windblown climate is protected from the fiercest of winds by the Langres Plateau.

As to why Pinot resides on Kimmeridgian soil in the vicinity of Chablis (why not cash in on Chardonnay here?), the mystery bears more investigation. We know that the 20th century was hard on the region in general. Terrible weather in the decade following post-phylloxera replanting resulted in massive loss of crop and economic devastation. The arrival of WWI and the loss of a great deal of the male population made the preceding years look like salad days. While mounting the slow recovery from WWII, the entire region endured the ruinous frost of 1956. By 1970, wine growing had largely been abandoned, and only five hectares of vines remained in Epineuil. Slowly, viticulture has been coaxed back (to the tune of just over 100 hectares), but Epineuil lives in the eternal shadow of Chablis, which suffered equally but recovered more robustly.

In parallel, Dominique Gruhier has endured his own Job-like series of afflictions while on his path to becoming a vigneron. The misfortune he and his family experienced is almost comical in its totality, and we suggest you visit Becky Wasserman’s long Gruhier webpage for details. You’ll enjoy this bottle even more after reading the whole story. Simply put, this is remarkable wine. Its deliciousness is self-evident in its deep cherry fruit and powerful mineral notes. Yes, there’s a notable herbal tinge when you first approach the wine, indicative of Pinot’s struggle to attain ripeness here. But keep sniffing and drinking. In moments, you’ll acclimate to the wine as your palate discovers that the hint of greenness actually accentuates the fruit’s purity. The evocation of cherries is not like any jam or pie, but rather crisp, fresh, firm cherries as they come off the tree, snappy to the tooth, the hint of summery leaves and stems. Without a doubt, this is one of the greatest deals for Burgundian Pinot Noir in our book and in the market in general. Dominique is redefining Epineuil and the possibility of red wine from Burgundy’s extremities. If you love this, we suggest you order more. It likely won’t be a secret for much longer.

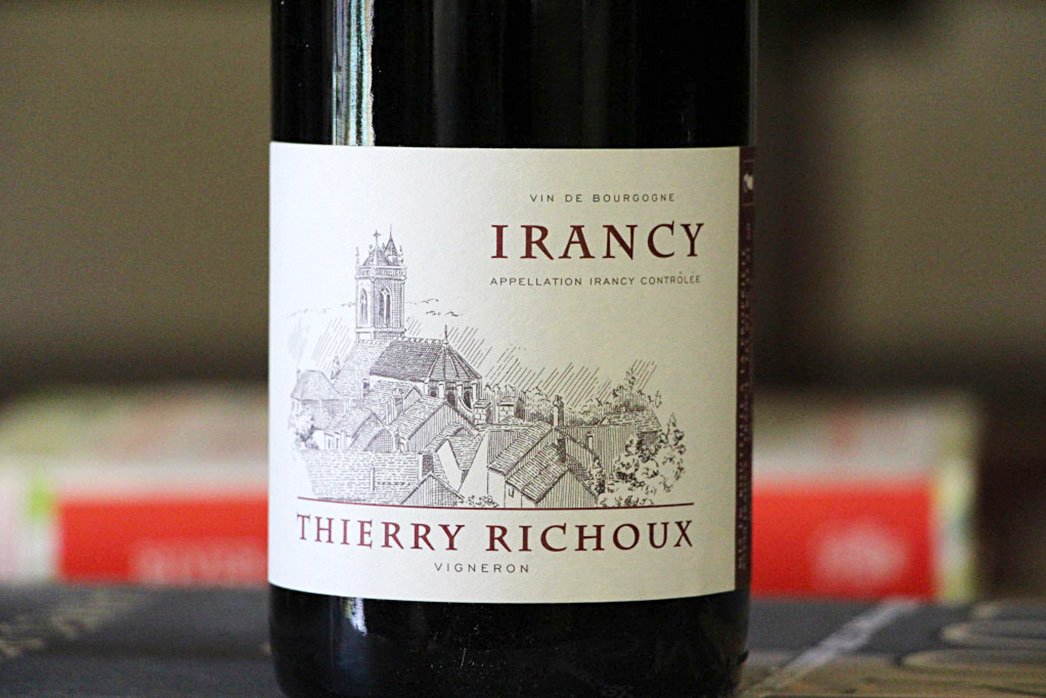

Speaking of dwindling secrets, the extraordinary quality of our final wine, the 2013 Thierry Richoux Irancy, is quickly becoming known in the sommelier world. The only thing holding back Richoux is the name of his village. Hard to say who has it worse, Dominique Gruhier, who makes wine in an appellation no one has ever heard of, or Thierry Richoux, whose village’s reputation is tainted by the association of wan, weedy Pinot Noir blended with César.

Just 15 km southwest of Chablis (Epineuil is northeast), Irancy has always been a Pinot Noir village. Once, long ago, celebrated (though what region can’t claim that?), Irancy Pinot Noir was only allowed the Bourgogne Rouge appellation until 1999, when it was given its own name. Since then, its growers have been working hard to restore the quality of its wines. Richoux is probably first to have truly crested that wave.

If you detect cherries in the wine—and we certainly do—it fits the area, as Irancy is still studded with cherry orchards, which share the slopes of the protected horseshoe of a valley with Pinot Noir vineyards. The partial enclosure of the valley shelters it from the lashes of harsh weather, while trapping a modicum of warmth to ripen the fruit. Fruit can get ripe here, but it’s a lower level of ripe expression than we’re used to in the Côte d’Or.

The genius of Thierry Richoux, as we see it, is that, rather than trying to make Pinot by Côte d’Or standards, he’s embraced the nature of Irancy and figured out how to turn it into utterly beguiling wine. His wine presumes nothing. It’s light colored, a hazy ruby red. To some that might connote rusticity, but to us it communicates confidence. When grapes aren’t richly ripe or deeply colored, he leaves no part of their material behind, as they provide silky texture and complexity. He preserves delicate flavors by letting them alone—the wine’s first year is in steel tank, it’s second in big oak foudre. That combination, which has nothing to do with how classic red Burgundy is made, produces a wine that has both the internal resources to age and the tender exterior to reward earlier drinking. The flavors, like Gruhier, are a spectrum of cherry, mineral, leaves, flowers, and earth, though Richoux’s are even more broad, playing to extremes while they dance about the middle.

The cool-climate nature of these Pinots provides a lot of their charm. They are, foremost, wines of texture. Their lacy fabric is a cool-climate hallmark, hard to come by in warmer places. As you settle into drinking these wines, you will find momentum because of the addictive beauty of the texture. So, like Thierry Richoux, banish expectations for Pinot and embrace these flavors and textures. Furthermore, know that, thanks to a changing climate, we are perhaps coming into the greatest era for winemaking these places have ever known. And not too many people know it yet!

Happy drinking!

The Source