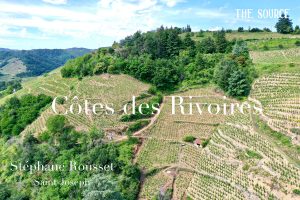

Boca Vineyards of Davide Carlone located in the Alto Piemonte foothills of the Alps

(Download complete pdf here)

Prelude to our New Italian Arrivals

Scene I

Wines from Sicily, Campania, Liguria, Abruzzo, Lombardia, Valle d’Aosta, and even many parts of Piemonte, like Alto Piemonte, existed in relative obscurity up until less than a couple of decades ago, even for those considered “Italian Wine Specialists,” most of whom seemed to be from Italy. It was a time when boutique Italian wine importers found limited success in fine wine retail stores but couldn’t (and still can’t) break into the big-brand Italian restaurant wine lists. Slowly, they began to chip away at traditional restaurants run by Italians and the French-dominated import wine programs in restaurants outside of the corporate mold. Many restaurants that were already working heavily with boutique French wines had few openings in their small Italian section for something interesting. And of course, there were exceptions that were already ahead of the game.

I remember pre-millenium sommeliers and wine-trade pros making fun of backwater areas in Italy that grew food-producing crops in-between vine rows (“what fools,” most of us blinkered wine pros thought), and that much of Italy was still nearly medieval. Many of Europe's great terroirs of that time were finely manicured dirt and rock vineyards with not much else that resembled anything natural. Cover crops were around, but we know that’s no substitute for a region’s natural biodiversity. Winegrowers that produced actual, edible food inside their vineyards for their family and animals were thought to be simple-minded. Many of us wondered how these rural Italians could possibly think they’d make high-quality, authentic, terroir-focused wines with all that mixed agricultural input from so much life and biodiversity between their rows taking energy away from the vine’s productivity. Most of us don’t think like that anymore at all.

Creative chef culture began to play with more Italian products and recipes mixed into their largely French-influenced food. These changes ever so slowly shucked sommeliers from the outdated Court of Master Sommeliers study program traditions that had little to do with indigenous Italian wines other than their glut of data-filled flashcards. The doors had finally started to creak open for small-house Italian importers to focus on this new terrain, and the momentum quietly began.

Recession in the late 2000s forced restaurants with deep cellars into a selloff. Furthering the movement toward smaller producers were the reduced budgets restaurants now had as they tried to return to normalcy and refill their cellar bins. They also shifted to much shorter lists with constantly changing selections, which not only opened the doors for those who had previously tried and failed to break in, but also for young and hungry new importers, like us. To support the uprising and force customers to venture away from Chianti, Brunello, and Super-Tuscans, some Italian restaurants even purposely began to leave them off of by-the-glass lists (and a few off their lists altogether), explaining that if they had a Chianti by the glass with the other nine reds poured, Chianti would sell 80% of the time, leaving some of the others to deteriorate before the last glass was poured. The indigenous Italian wine market cranked into full boom and it’s no longer a movement, it’s now an establishment.

In 2004, after eleven years of bouncing around between more than a dozen restaurants and working three harvests in Santa Barbara wine country, I quit my final restaurant gig at the then famous Santa Barbara wine outpost, Wine Cask, where I was the Sommelier and Restaurant Manager. I sold all my possessions (except my small wine collection and some childhood collectibles) and headed off to Europe for a six-month bicycle trip through its famous cities (and hit their museums), and worked through just under a hundred wineries throughout Austria, Germany, Northern Italy, France and Northern Spain. I don’t know how many times I paged through A Moveable Feast during that time, and I finally felt like I was living that bohemian life for those six months—in a tent one day and a winegrower’s guest mansion the next; it’s a life that I often crave to reenter today. I haven’t been able to just up and quit a job like I used to, sometimes a couple times or more a year, ever since I started our wine brokerage and import company fourteen years ago.

My lengthy bike-powered pilgrimage that brought me through Barolo and Barbaresco kicked off a new beginning (or more accurately, obsession). Already lightly seasoned and interested in the epic Nebbiolo wines of the Langhe, it was the painful biking up Barolo’s steep and windy hills for visits with many famous vignaioli that gave me an even greater respect for these wines. We were often gifted with bottles from our tastings or managed to buy wines directly from the growers at a poor-bicycler discount to take back to our campsite and infuse ourselves with the intoxicating fog of Nebbiolo.

Most of the dozen or so restaurants where I worked before my time at Spago Beverly Hills and then Wine Cask had sparse selections of Italian wines but were flush with French and Californian, along with dashes from other countries here and there. Burgundy was, even in the early 2000s, still a slightly esoteric category for the general population. Often unaccounted for is the 2004 movie Sideways as one of the pivotal turning points of Burgundy’s move into the mainstream. With Pinot Noir’s place in the story as the protagonist and Merlot the antagonist—which was just too close to Cabernet for it to avoid collateral damage—it became the new global trend, absolutely crushing Syrah’s rise and bringing Merlot drinkers to an existential crisis. With many of these new Pinot enthusiasts (Noir seemed to be globally dropped from the name outside of label requirements, like Cabernet no longer needed its partner Sauvignon) with bigger budgets eventually graduating to Burgundy. It may be hard to believe for those who walked in the door in the last ten years, but wines like Beaujolais were not a significant category for even the mainstream wine enthusiast, and Jura was frightening for all but the fully committed Francophile with a high tolerance for the unusual. I admit, I myself took a while to come around to Jura wines too, but I certainly did.

A Burgundy saying that must have gasped its dying breath about a decade ago that went, “Bought only on presell and closeout,” seems ridiculous now. The “presell” part of the saying remains truer than ever while the latter couldn’t be further from today’s market demand. Perhaps the start of the twenty-teens marked a turning point (at least for our company) where Burgundy importers no longer had to discount to finally get them out the door—with the exceptions of 2011 and 2014. Believe it or not, around 2009, a Beverly Hills wine merchant closed out some 2005 and 2006 wines from Jean Grivot, D’Angerville, and even some Roumier, among many other producers represented in the US by Diageo. I paid about $30-$60 per bottle, depending on the cru.

The wine world has gone completely mad on pricing. Elite and micro-producer prices are embarrassingly stupefying and never worth the price, and the great secrets once whispered only among the trade are a thing of the past, seemingly for good. Only ten or fifteen years ago you could find truly amazing deals, or at least easy access to just about every top wine from Burgundy without any additional and unusually high markups. In Southern California (surely elsewhere too, but this is where I used to snag them), D.R.C. could be found inside grocery store glass cabinets in Santa Barbara with standard markups (including La Tache and Romanée-Conti); Rousseau’s Clos Saint-Jacques and Clos de Bèze collected dust at Wally’s; Clos Rougeard and Thierry Allemand were kicked around the concrete floor at Wine House for probably an entire year before the last bottles found a home, and gray market Fourrier and Raveneau sat across each other bored for months in different corners of Wine Exchange, waiting for me to drop in and fill an entire grocery cart for $60 or $70 a bottle—a little extra on top for the time, but pennies compared to today.

Piemonte’s Langhe wine regions have also had a severe uptick in interest and investment in the last years. Like all the other great wines, I could walk into those same L.A. retailers ten years ago and get just about anything I wanted: G. Contero, G. Rinaldi, G. & B. Mascarellos, Burlotto (which had an outrageous climb from $60 to about $300 in two years), etc. The greats of Barolo (more than Barbaresco) seemingly snuck right out of reach in only a couple of years for those of us with modest and medium budgets, just as Burgundy did more than a decade ago. These unwelcome departures left many of us unquenched for the noble tastes and particular house styles. Truly great Barolo and Barbaresco can still be found at fabulous prices (just look at Poderi Colla), but there are so many with medium to high prices that are more likely to underdeliver than live up to expectations.

Fret not, dear reader! It’s not a time solely for lamentations for our past access to today’s elites! The horizon is always full of new arrivals from forgotten or overlooked lands that once shined with success before falling out of sight, many of which were showered with praise by the royalty of the past, their noble grapes preserved by generations of working-class heroes who kept them alive.

But with the price increase crisis of the Langhe and soon Alto Piemonte, how can any other Piemonte region compete in quality with Barolo, Barbaresco, and the wines of Alto Piemonte? Where in Piemonte could possibly be next? My hunch might surprise you, or maybe it won’t because you’re already on the trail…

La Casaccia’s Monferrato vineyards in Cella Monte

Prelude to our New Italian Arrivals

Scene II

The Monferrato hills are filled with untapped potential. Yeah, I know what some of you are thinking: “Come again?” (Long pause) But please, allow me to explain.

How exciting can Monferrato possibly be? Does the market even take this region seriously? These were regular thoughts when we first began to focus on importing Italian wine in 2016. Prior to then, my company that predated The Source brokered Italian wines in California for almost a decade with a few different Italian importers. The importers we worked with played a quiet but influential role in the emergence of backwater Italian wines. One was strong in Italian and French “natural” wine producers before natural wine stormed the market. (Eventually he went out of business, partially because he was way ahead of his time, and the other part was that in the end he was a crook.) The other continues to successfully run a collection focused on clean craftsmanship with most of the selection from the Italian road less traveled. Each had their token price-point Monferrato producer or two, usually a couple Barbera d’Asti, but not much more.

I never set out to plant a big flag in the Monferrato/Asti area. Like the Italian wine importers I once worked with, I was in search of a token Asti producer to supply us with some value Barbera. Then something happened, something that has happened many times before: I witnessed potential that needed a strong and friendly nudging.

Sette’s Vino Bianco

Exciting Potential? How? Why? Who?

Monferrato’s first advantage starts with the fact that they have few expectations for the wines they produce. (Probably the most pertinent is the expectation that they should have good prices and be cheaper than Langhe wines.) Most importantly, many don’t play the Nebbiolo game, so they don’t have the burdensome weight of navigating today’s grape royalty. Nebbiolo-land comes with familial and regional baggage. The iron-grip of the most recent generational lines that built the family up from the poorest area of Italy to one of its wealthiest isn’t keen to let the kids wander too far off the path. Ok, they can tinker with Dolcetto, or even Barbera, but Nebbiolo used for their Barolos and Barbarescos? The vignaioli of Barolo and Barbaresco are no longer just grape farmers and winemakers, they’re bigtime businesspeople, and their task now is to push the same rock, the same direction, every vintage.

Monferrato’s fewer expectations can lead to freer thinking as a community. Freer thinking leads to greater experimentation. Experimentation leads to breakthroughs. Breakthroughs change the game. When games change, people follow.

Monferrato has their own historical grapes, which means they won’t always be second or third division Nebbiolo land. They can be first division Barbera, first division Freisa, first division Ruchè, and, what I believe could be the most significant category uptick, they undoubtedly will be first division Grignolino—a variety that was considered grape royalty for centuries.

Another advantage is that they have the terroir with enough talent to go beyond “good value wine” and into the world-class. The ingredients are there: limestone and chalk with extremely active calcium, sandy limestone, gently sloping hills (preferential to steep ones with looming climate change toward hotter temperatures) with great variations of soil grain to put grapes on their most favorable soil types (Grignolino on sand, Freisa on clay, Barbera in the middle), tremendous biodiversity with swaths of indigenous forest between vineyard parcels and sometimes right in the middle of them along with a multitude of intended crops (well beyond the occasional hazelnut grove as seen in much of the Langhe’s prized vineyard areas where grapes aren’t suitable), and a climate that’s conducive to organic and biodynamic vineyard culture.

Vineyard soil cut demonstrating the layered geology at La Casaccia of limestone, chalk, limestone-rich clay and siliceous sands

The x-factor here is that Monferrato’s growers surely include ambitious and creative kids with dreams to build. Their parents and grandparents lived in relative isolation in this Italian backcountry while other nearby regions went from poverty to wealth in a single generation. Most of the Gen Xers are in the family driver’s seat, the Millennials are working side by side with mom and dad, and the Zoomers are at school, and all three of these generations are exposed to the world around them through their social media feeds. They have witnessed the incredible success of Langhe. They see that their northerly wine neighbor Alto Piemonte is not only rising, but it has also arrived in a big way. They realize the potential of the natural wine movement and many will want a piece of it. (But do it cleanly, please!). There are now openings to make whatever style of wine they want because there are fewer shackles; they can stay and improve on the traditional course passed down for generations and/or get creative in their own way and veer from tradition. Whatever the path they choose, I think they will have more freedom than the average kids of Barolo or Barbaresco, in fact, more freedom than any other Nebbiolo-focused region.

Another factor is immigration, and I don’t mean people from other countries, but those from neighboring Langhe. With the increase in frequency of the Piemontese selling their most prized vineyards to foreign investors for fortunes nearly impossible to recoup in the wine business (that is, without flipping the property to the next high-bidding trophy hunter), how does any financially challenged Langhe youngster filled with inspiration and great knowhow (from a family that works for the landowner or in the cellar) get out of first gear? They have to move.

This is what happened with the young Gianluca Colombo and his business partner, Gino Della Porta, with their new Nizza-based winery established in 2017. Gianluca is a consultant for many reputable Langhe producers, and he also makes his own small production Barolo wine. Gino is a mastermind, connected throughout the wine world, responsible for helping develop one of Italy’s most important importers, and helping to manage some of Italy’s most recognizable small cantinas. Only minutes into meeting this two-person comedy act, with their incredible proficiency and ambition for their project, I knew they would be a force; not only a force for their own project, but I am sure they, and others walking the same road into Monferrato, will inspire other producers in the Monferrato hills to break through the glass ceiling of their own making.

Two New Monferrato Producer Snapshots

(Their wines covered in greater detail further below)

Sette's Gino Della Porta and Gianluca Colombo

Sette, Nizza Monferrato

The Monferrato/Asti area is Piemonte’s new wine laboratory, and experimentation is extensive at Sette, where they’re looking to expose new dimensions of their local indigenous varieties. The comedic and talented duo of the experienced wine trade pro, Gino Della Porta, and well-known enologist, Gianluca Colombo, founded Sette in 2017 with the purchase of a 5.8-hectare hill in Bricco di Nizza, just outside of Nizza Monferrato. Immediately, a full conversion to organic farming began, followed by biodynamic starting in 2020, the latter being a vineyard culture still considered somewhat radical in these parts. The wines are crafted and full of vibrant energy with focus and only a soft polish. There’s the slightly turbid and lightly colored, juicy, fruity, minerally Grignolino, and their two serious but friendly Barberas, among other goodies that will trickle in with time. Sette’s game-changing progressive approach and delicious wines (with total eye-candy labels) should ripple through this historic backcountry and bring greater courage to the younger generations to break out of the constraints of the past and move full throttle into the future.

La Casaccia's Rava family, Elena, Margherita and Giovanni

La Casaccia, Casale Monferrato

Even in Italy it may be impossible to find a vignaiolo who emits as much bubbling enthusiasm and pure joy for their work than La Casaccia’s Giovanni Rava; la vita è bella for Giovanni and Elena Rava, and their children, Margherita and Marcello. Working together in a life driven by respect for their land and heritage, they also offer accommodations in their restored bed and breakfast for travelers looking for a quieter Italian experience. Their vines are organically farmed and scattered throughout the countryside on many different slopes with strong biodiversity of different forms of agriculture and untamed forests teeming with wild fruit trees. Their traditionally crafted range of wines grown on soft, stark white chalk with layers of eroded sandstone are lifted, complex and filled with the humble yet exuberant character of the Rava family.

New Italian Wine Arrivals

Monferrato Reds

Grignolino is coming. I don’t just mean that we have some arriving this month (which we do), I mean Grignolino is coming. We have seen a considerable increase in interest since our first batch arrived from Luigi Spertino, followed by Crotin’s—the latter of which easily fits into the by-the-glass range, while the former does not. We went from about a hundred cases between the two each in our first years to more than triple that this year with none left in stock six months after their arrival. Grignolino is coming, I say! This year, with the addition of our two new producers, Sette and La Casaccia, we have doubled that quantity just for the California market, and it's only double because that’s all the producers could provide.

Grignolino is the perfect Piemontese grape variety for today’s market. Its pale color is enticing and reminiscent of fresher vintage Nebbiolos with those unique Giuseppe Mascarello-red tones but with an even lighter hue. Seduced by their constant emissions of pheromonal scents fluttering out of the glass, accented with dainty, sweet red and slightly purple flowers, tart but just ripe berries and a little flirt of that indescribable but inimitable Piemonte red wine spice and earth, I remain smitten, if not completely infatuated. Superficially, simply made Grignolino is invitingly poundable, delicious fun, but in more intimate encounters its interior strength reveals firmness, respectability, nobility.

Mauro Spertino’s Grignolino, labeled with his late father’s name, Luigi Spertino, is what spurred my crush on this grape. Mauro (pictured above) has the magic touch surely mostly learned from his father, who revolutionized the method in which to navigate this charming grape that has a thin skin but more tannin-rich seeds than other Piemontese grapes, including Nebbiolo. Mauro is a bit of a magician in the cellar, so there’s no doubt that he took it to the next level to where it is today. Many think his Grignolino leads the category in Piemonte, and I agree. One answer for tannin management with this seed-heavy grape is to employ shorter macerations with pressing once the interior grape membranes break down, but prior to fully exposing the seeds to the alcohol when the extraction of these harder tannins can happen. With this approach, one can also pick earlier to highlight the variety’s natural charm with an even redder, crunchier spectrum of fruit ripeness—for me, the hallmark characteristics I think serve this wine better than those with more wood contact and ripeness on the vine. All of this makes for a wine with a lot of pleasure while retaining its regional DNA. Grignolino seems to me to be close in its ethereal characteristics to Nebbiolo.

Grignolino’s time in the sun is on the morning horizon. Ideal for today’s consumer in search of lighthearted but authentic and terroir-rich wines, it offers the classic cultural tastes and smells of the Piemontese wine, but under the right touch with much less pain. Piemontese reds are known to beg for food, but despite Grignolino’s naturally high acidity and Dolcetto’s bigger tannins (another underrated, delicious Piemontese grape) they don’t need food to deliver harmony and are quite fun to drink alone. Both are immediately accessible and fair well when made with a simple approach in the cellar, unmarked by wood aging if wood is employed at all.

According to Ian D’Agata in his book (a must for anyone serious about Italian wine, or just simply interested), Italy’s Native Wine Grape Terroirs, the Grignolino wines were prized as far back as the thirteenth century but lost favor in the last thirty years and were replanted with other grapes that had a stronger market value in the Langhe and elsewhere. D’Agata pushes the merits of Grignolino in his book and loves the wines, and I understand why. I’m only a little disappointed that it took so long for me to see its light! It seems to have all the ingredients to really thrive in today’s market that’s more than willing to pay for the highest levels of nobility and extremely fine subtlety in the sip. I would even venture a guess that if Grignolino had held court in prized Langhe vineyards that with today’s swing for many from power to elegance, it may have held the number two spot just below Nebbiolo, leaving Barbera and Dolcetto to duke it out for third. I think Grignolino can be that good but clearly within the more gentle wine context, it can have big tannin and acidity. What brave soul would dare rip out Nebbiolo in a prime position in Barolo or Barbaresco to see what happens with Grignolino in its perfect spot? Any takers?? Maybe many would need to get over their addiction to the smell of money first…

In places like north Monferrato, under the labels of Grignolino del Monferrato Casalese, they can be gorgeous and with, on the average, a little more substance due to their greater limestone marl content mixed in with sand than Grignolino d’Asti’s sandier soils, without losing their freshness and charm. Of course, these regional soil elements vary from plot to plot, so broad generalizations often need to be thrown out the window. Between the Grignolino from our first producer from the area, Crotin, followed by Spertino’s game-changing wines, and now wines from both La Casaccia and Sette, we have a very special collection.

Starting with what I perceive as the most elegant and light of all these perfumed and somewhat dainty Grignolinos is Luigi Spertino’s Grignolino d’Asti. About as lithe as a red wine can be, its light red, slightly orange-tinted hue is pale enough that in a dimly lit room you might think there’s nothing in the glass until you hold it up to a light to illuminate its striking color. Despite the lightness of the wine, a rosé it is not. The palate is a showcase of fragrant classic varietal notes of fresh berries and subtle but sweet, darker-hued flowers, and its light but firm texture marks the separation from what a rosé would maintain, as do the complexities of the grape skin phenols forged through the fermentation with a longer skin contact (which is about eight to twelve days, depending on the year). After four or five months in steel, the wine is bottled.

All four are elegant, but perhaps next in line for the most elegant is Sette’s Grignolino Piemonte DOC, a wine that will not arrive until some months from now. Its delightful turbidity and time spent in Tava amphoras for eight months coupled with its sandy soils brings a more lightly creamy texture and body resulting in a more playful interaction. (Tava amphoras are cooked at extremely high temperatures which tightens the porosity significantly over those cooked at lower temperatures, leading to customized micro-oxygenation level for Sette’s amphoras that have similar porosity to that of a 15/20hl oak barrel and also impart no taste to the wines.) My first bottle of their 2020 convinced me that I could easily make it one of my weekly pulls from the cellar. Riding the line between well-polished, medium structure and texture, this finely tuned Grignolino is bottled fun, just like the owners of their project, Gino and Gianluca. Unfortunately, similar to Spertino’s Grignolino, it will be in short supply when it arrives in early fall.

La Casaccia’s Grignolino del Monferrato Casalese “Poggeto” could be viewed as sharing the middle spot with Sette on the elegance chart. There may be no region more historically famous for high quality Grignolino that still focuses on this grape as a category leader than the areas around Casalese. I’m newly addicted to the style of the La Casaccia wines crafted with the mind, big heart and happiness of Giovanni Rava and his wife, Elena, and their charming, contemplative daughter Margherita. Always grown on the top of the hills on the sandiest soils loaded with chalk, the wines are filled with the spirit of deep joy and generosity of the family delivered with impeccable craftsmanship. La Casaccia’s style may be the most classical in the sense that they don’t go to the extremes as Sette with their modern touch of turbidity coupled explosive aroma, or Spertino’s sushi-style Grignolino, but rather an ode to the traditional craft in search of a spherical balance throughout the entire wine.

Crotin’s Grignolino d’Asti “San Patelu” may be the most glycerol and full-colored but bright red for this naturally pale variety between the four. The Grignolino at this cantina always shows the nuances of the vintage but typically leads with dense but bright perfumes of the grape’s classical notes, a little Ruchè-like in perfume and weight, in a Burlotto-esque, Verduno Pelaverga way, senza le note di pepe bianco. Crotin’s Grignolino usually shows the greater structure between the group, likely a hallmark of their comparatively colder region, and the direction of the family with the advice of Cristiano Garella, their consulting enologist with a sharp eye for detail and an unflappable commitment to finding the truth in wine without applying any greasepaint for the international market.

Ruchè caught me off-guard. I don’t recall tasting this grape prior to a few years ago at the cellar of Crotin with some of our staff and the other co-owner and General Manager of The Source, Donny Sullivan, and I don’t think anyone who tasted some would forget it. I saw a bottle of Ruchè sitting around in the restaurant of their agriturismo with a label on it I didn’t recognize, so I asked about it. Federico Russo, the eldest of the brotherhood (and seemingly their leader), happily pulled the cork as he told me that they made the wine for that winery. As explosive as any wine can be out of glass, it had an array of perfumed bright red berries, red ripe stone fruit and spice brightened my face with delight. My first thought wasn’t whether I liked it or not, but was a realization that today’s market interested in unapologetically perfumy and delicious wines could blister through a wine like the one in my glass, wowing first-timers with its pleasure bludgeon. (This especially applies to winebar by-the-glass programs.) About two minutes later I blurted out, “This wine is delicious,” with Donny nodding his head in time with mine, scrunching his eyes and giving me his half-smile that says, “This is a no-brainer.” So I asked Federico, “Can you make some for us?”

Shortly after returning to Portugal, Federico sent me a six-pack of the Ruchè producers he thought were best representative of the region to give me a better context. Most of the wines were quite high in alcohol, which made them harder to appreciate than the one he made, which was 13.5%. Crotin’s 2021 Ruchè di Castagnole Monferrato “Monterosso” is the second year they’ve bottled the wine that they had already been making, this time in their cellar under their own label. Our first year we brought in fifty cases to test the market and, after a strong showing that made short work of the 2020, this year we have more than double the quantity, though we could’ve easily bought a couple hundred cases more if they’d had the stock. The grapes come from an organically farmed site mostly on an alternation of contrasting red soils with a lot of iron and chalky limestone. The wine is raised in stainless steel vats until the following summer for bottling. Crotin’s style contains this flamboyant variety; it’s nuanced rather than pushy, and it’s easy to say yes to a second glass, unlike five of the six he sent me that clocked fifteen degrees or more of alcohol. I believe Ruchè has an opportunity in today’s market, but from a long-game perspective, the other producers may need to reel in the punchy fruit and spice, otherwise the grape may burn brightly on the market for a minute only to fizzle out just as quickly.

After Grignolino, Freisa slowly worked its way into my favor, and one day I met the one I wanted to marry. I never paid much attention to it other than being privy to its genetic relation to Nebbiolo but being known for lacking the same level of finesse, depth and ageability. What put Freisa into my radar initially were the ones from the great producers like G. Rinaldi, G. and B. Mascarellos, Cavallotto, Brovia, and Vietti, who all keep it in their ranges still. (They must still have them for a good reason, no?) It’s true that youthful Freisa can approach with the grace of an angry bull, but in the right hands, it’s untamed nature can at least be harnessed and led toward a gentler appeal so that maybe it ages into something unexpectedly wonderful. I have a hunch that Freisa will eventually gain the respect of the general international community of Italian wine lovers. It just needs the right ambassadors, although the mentioned Barolo producers are not a bad start! However, it’s merely a guess because I don’t know, but I bet the Freisa still grown in Barolo and Barbaresco is positioned on the vineyard in subordinate locations to Nebbiolo. Few winegrowers can justify keeping Freisa in a prime time Nebbiolo spot, if not only for historical preservation, then for financial reasons.

I don’t plan to stand on the hilltop to shout the universal merits of Freisa as I will with Grignolino (although there is one that swept me off my feet), but at the very least I’d say it’s an inexpensive entry-ticket to authentic Piemontese reds that covers all the bases and can under the right shepherding and prime vineyard position yield very special results. In a Decanter article I read about Freisa, Ian D’Agata is quoted as saying that aged Freisa is sometimes hard to distinguish from Nebbiolo. Despite my lack of experience with this, I believe him.

Crotin’s Freisa d’Asti is one of those wines crafted in a traditional way, despite spending all of its time in concrete and stainless steel. What I mean by traditional (which I don’t think was specifically concrete aging for a short period as they do) is that the wine is not vinified to embellish the fruit. It’s built on structure and subtle aromas and in context within the full range of Crotin’s other reds—Barbera, Grignolino, Ruchè, and now some Nebbiolo—it’s the most savory and least fruity wine in the range, although it still has plenty of fruit that comes through more when enjoyed independently of the other wines. This version is for the old-guard Italian wine lovers, and for the price it makes it all the more attractive for the same seasoned buyer who gets sticker shock around every corner of the Italian section of the wine shop now; well, except with wines from the Monferrato hills!

I don’t know what Giovanni Rava did with La Casaccia’s Freisa Monferrato “Monfiorenza,” but it swept me off my feet. Their Grignolino is lovely and one of the best concrete-aged, fresh, beautiful, and substantive wines in the Grignolino world, but their Freisa rendered me speechless with an ear-to-ear smile the first time I drank a bottle of the 2019 last summer with the family on a breezy and warm summer night. I didn’t know Freisa could do that! I went to La Casaccia to ask Giovanni for their Grignolino’s hand in marriage but left the alter with his Freisa! That day I also had the best wild cherries in my life—clearly a day to remember. I’m not sure about this wine’s ageability, but who cares; it’s a wine to feast on in its youth and wait as patiently as possible for the next scrumptious batch. We received only 60 boxes of the 2019 vintage but a lot more of the 2021 is in route soon. I think the 2021 is going to be just as good.

Despite its non-native status in Monferrato, Barbera is the local sheriff and the breadwinner. Apparently, the variety originated in southern Italy centuries ago (perhaps Sicily or Campania, but the debate about its origin and actual arrival to Piemonte is still alive) and began its mass proliferation sometime after phylloxera hit. Today, it’s ubiquitous in much of Piemonte and there is a lot of it in the marketplace, which, thankfully, keeps the prices down, even from producers in Barolo and Barbaresco.

Barbera is indeed a bit of an outsider in Piemonte. It’s easy to spot in a blind tasting of Piemontese wines because of its abundance of acidity and lack of tannins—the exact structural inverse of Dolcetto. It also typically requires a greater alcohol potential to achieve phenolic ripeness that moves it away from hardened tannins (the few that it has) and the potential for unbalanced high acidity. Barbera is also uniquely suited for its best results with warm summer weather during the daytime and nighttime, the opposite of the others Piemontese grapes that need the daytime heat but colder nights to reach their heights—another clue to its possible origin from the south where day and nighttime temperatures don’t fluctuate like those in the north or deep inside the Apennine range.

Monferrato is a Piemontese territory that dates to medieval times and includes much of today’s provinces of Asti and Alessandria. It’s a little confusing how they separate the region out, but think Toscana with its two main wine provinces, Siena and Firenze (although there are ten Toscana provinces in total). We have delicious Barbera wines coming in from all four of our producers, but they are also all quite different. Both Crotin’s Barbera d'Asti and La Casaccia’s Barbera del Monferrato “Guianìn” are classically styled Monferrato Barbera without much “hand in the wines.” Both are raised in neutral, non-wood vessels and grown on calcareous sands with Casaccia’s a higher content of chalk. Perhaps Crotin’s is more defined in acidic profile and slightly denser body with darker fruits only nuanced by red. La Casaccia’s is gentler and less compact but with the same depth as Crotin’s.

Our two Asti producers of Barbera, Sette and Spertino, make two very different wines inside its most revered appellation, Nizza, the newest member (since 2008) of the Italian DOCG family. Nizza is special and what many consider to be the leader for this grape variety for the entire globe. As many writers add to that shared belief, the Langhe could be the top spot were it not for the prized exposures reserved entirely for Nebbiolo—and rightly so!

Sette produces two different Barberas, both grown inside the Nizza DOCG, within the commune Nizza Monferrato, from the same 5.8ha plot in conversion to organic (2017) and biodynamic culture (2020) on a south face composed of calcareous marls and sandstones: one bottled as Barbera d’Asti, made from vines with between 20-40 years old on chalk and sandstone, and the Nizza (also composed entirely of Barbera; pictured above), from mostly 80-year-old vines on limestone, chalk and sandstone. For both Barbera d'Asti and Nizza they use an old Piedmontese winemaking technique of waiting for the must to reach 10-11 degrees of alcohol and then use a wooden grid to submerge the cap for a more gentle infusion approach for the latter two-thirds (or more) of the maceration time to softly extract while the wines reach their textural balance as it is tasted daily. This process lasts between 30 to 50 days, depending on the vat and the year, with Nizza always a bit longer than the Barbera d’Asti.

Following the pressing, the Barbera d’Asti makes at least a year of aging in the cellar with concrete vats prior to bottling and release, while the Nizza is aged for a year in 30hl Stockinger barrels followed by six months in concrete. The result for both of these wines is their softer structure than the typical Barberas from the Langhe, but also with more savory notes and more profound depth. Sette’s Barberas are extremely serious wines with massive potential. They are on the more technically tight craft side without sacrificing their approachability and friendliness. Sette is an extremely promising new cantina.

Spertino’s Barbera “La Bigia” is another demonstration of Mauro’s alchemistic touch and the unique signature on his wines. I never imagined that a Barbera could taste and evoke such emotion as his, and in this fuller style. He somehow manages to create duality between bright light and deep darkness in the same wine. Its twenty-year-old vines grow in sandy calcareous soil and the grapes spend around twenty days fermenting, then the wine is aged in the cellar for half a year in old 5000-liter botte. Aromas of a dense, fresh wet green forest, with taut but mature wild black berries, black currant and a potpourri of underbrush swirl out of the glass. The palate is powerful, supple and refined, like the final polish on a marble sculpture. The naturally bright acidity inherent to Barbera keeps this brooding wine that tips the scales in alcohol content toward modern-day Barolo while remaining in perfect harmony. Like all of Mauro’s wines, this is singular unto itself and must be experienced.

Monferrato Whites

I didn’t realize it until I began to write, but the only three white wines we import from Monferrato are all very different and a little atypical for the region.

Mauro Spertino’s range is unique in that he has both wines that are full, powerful and still graceful, while others are ethereal, subtle and as light as can be while still maintaining a clear voice of their terroirs. Spertino’s Metodo Classico fits into the latter realm. Mauro’s 2018 was a thrilling start for his first try at it (but still not surprising with this guy’s golden touch), and the arriving 2019 is a natural step up for a few reasons: it was a better year for Pinot Noir than the hot 2018 vintage, and he had one more year under his belt to make his preferred micro-tweaks. The vines were recently planted toward the top of his extremely steep, sandy calcareous vineyard in Mombercelli, but cleverly placed on its north face to preserve as much freshness as possible. The wine is vinified in stainless steel and spends twenty-four months on its lees before disgorgement. It’s very pretty wine.

La Casaccia’s Chardonnay is grown on almost pure chalk and it tastes like it. It’s a fabulous alternative for those in search of terroir-dense limestone Chardonnays with a smile-inducing price tag. It’s probably true that no one is rushing out in search of Monferrato Chardonnay, but if zippy, fresh, and minerally Chardonnay is your thing, you should give it a go. It’s loaded with all of that indescribable magic imparted by extremely calcareous soils—think Burgundy’s stainless-steel Chablis, or Hautes-Côtes Chardonnays. I expect our first batch to evaporate at its bargain price.

We know Moscato as a still wine is one of the hardest sells. Once I received Sette’s Bianco entirely from Moscato, I was skeptical as I pulled the cork. (Though its gorgeously inviting label, pictured further above in the newsletter, could sell just about anything inside.) I tried so hard not to like it before tasting it because I could already imagine it on our closeout list. However, once in the glass you may share my same surprise. The annoying, cloying characteristics of Moscato are absent and all that’s left are its most flamboyant traits, toned down by its eight-hour skin contact before fermentation, its aging in Tava amphoras, and its light leesy haze. There are so many pleasantries it’s hard to dislike, even if it’s not your typical style. Stylistically, there may not be a much better pairing for nigiri sushi with its floral and gentle spice notes, and texture similar to unfiltered sake, a perfect match for sticky rice under raw fish with ginger and wasabi.

Alto Piemonte

Fabio Zambolin, Costa della Sesia/Lessona

My visit last year was business as usual, nothing particularly new to report, just another good time with Fabio and his delicious wines. But a couple months ago during our visit, I found him and his tiny production overwhelmed by orders from all over Italy. Restaurants were asking for unusually high quantities of both wines—apparently the result of a series of tastings in Rome and Milan. Last year we took greater quantities before the demand went through the roof and we have the same this year despite the newfound fan base. Lucky us!

Both of Zambolin’s new arrivals are 2019s, a Piemontese vintage we’ve all waited for since the grapes came off the vine. It lives up to the hype and I suggest if you want these you should speak up soon. We are not yet sure if that frenzy from Italy will carry over into the US too.

As many of you who already follow Fabio, you know that his garage-sized operation and his tiny plots of land are in and around one of Alto Piemonte’s most historically celebrated regions, Lessona. Fabio has a bureaucratic challenge in that his winery is out of the Lessona appellation but his vineyards are inside its borders. This makes his wine only qualify as Costa della Sesia appellation. His Costa della Sesia Nebbiolo “Vallelonga” is purely Lessona from a terroir perspective. The overall style here is finesse over power, a combination offered to the wine because of its sandy volcanic soils, and, of course, Fabio’s stylistic preferences.

Zambolin’s Costa della Sesia “Feldo” is also grown inside of Lessona but doesn’t adhere to the grape proportions required to fit within Lessona’s DOC rules. A field blend of old-vine Nebbiolo, Vespolina and Croatina, I never imagined this blended Piemontese wine without a dominant grape variety would be one of our top sellers; Feldo continues to prove my first instincts wrong with every delivery. It has gobs of festive aromas and flavors (at least compared to other wines in an area known for often producing more solemn, strict wines in their youth), with even a dash of pretension—it’s well-made Northern Italian glou glou. There’s a lot of seriousness tucked in there too—not surprisingly considering the perfectionism with which Fabio organically farms his vineyards and his meticulous work in the cellar.

David Carlone, Boca

We finally have our second batch of Davide Carlone’s wines arriving. The first set was gobbled up in a craze during my visit to California in November, when I showed them on three different occasions with our teams between San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego. (Big shout out to SD! The restaurant scene down there is happening; I was impressed.) Most of the buyers looked bewildered, like “Where have these been all my life?” I thought the same thing the first time I tasted Davide’s new wines too and was convinced he is the real deal; someone to contend with, and someone to know. His newest releases will not disappoint. When we first started to work with Davide only a little more than a year ago, there was plenty of wine to buy—post-Pandemic stocks. But since then we’ve already been moved into the allocation game because of the high demand.

We were able to circle back for some more of the very successful 2018 Croatina, but the rest are new vintage wines. The 2019 Vespolina was one of the stars of our first showing and for many tasters it was their the top single-varietal bottling of Vespolina. The follow-up vintage, 2020 Vespolina is strong despite tough competition from the glorious 2019.

The 2019 Nebbiolo is a shoo-in: it’s one of best vintages on record with an ideally lengthy season (with the well-known Alto Piemonte enologist, Cristiano Garella, claiming it was the best of his professional life that started in 1998); it is perhaps the world’s most compelling red grape among only one or two contenders for top spot. It delivers high-altitude freshness with full solar exposure contrasted by cold Alpine nights grown on volcanic rock, a multitude of special biotypes (about eight or nine in this vintage with more to come), and utterly pure Nebbiolo goodness raised in steel.

The 2018 Boca is a spice rack of Nebbiolo biotypes (minimum of 85% Nebbiolo at Carlone) with 15% Vespolina. Both go through spontaneous fermentations on the skins (fully destemmed) for around a month for the Nebbiolo, and the Vespolina for 14-18 days. The wine is aged in 25hl Slovenian oak botti for eighteen months and then prepared for bottling. The different biotypes from all over Piemonte give this wine a great breadth of complexity, allowing it to hit a broad chromatic range of octaves from tenor to baritone to bass, all in wonderful harmony. However, the biotypes with bigger structure (mostly from the south, in Langhe) are reserved for this wine, while the more delicate ones are used for Adele.

The 2017 Boca “Adele” prompted me to personally get in the game with Carlone by cellaring some wine in the US and Portugal. Boca Adele, named after Davide’s grandmother and his niece, is the higher toned of the two Bocas. It is made the same as the Boca appellation wine and is also a blend of 85% Nebbiolo and 15% Vespolina but is mostly composed of the picotener family of Nebbiolo biotypes which typically impart more elegance and softness to the wine than the clones from further south. Adele’s final blend is decided by blind tastings, but Davide and Cristiano tend to favor the picotener biotypes (particularly 423 and 415, which they describe as having wild fruit with a greater retro nasal finish and a stronger vibrancy that lingers longer on the palate). It’s a refreshing hallmark of some producers in Alto Piemonte, particularly many who work with Cristiano, that the top wines are often the most elegant and sometimes the lowest in alcohol, whereas many regions continue to place the “bigger” wines at the top of their hierarchy.

Ioppa, Ghemme

Ioppa continues their steady rise under the direction of enologist Cristiano Garella who was asked to work with the family in 2016 just prior to the unexpected passing of their visionary owner, Gianpiero Ioppa. Cristiano made an immediate impact and today we benefit from more than five years of his contribution to help them sculpt their wines. The 2021 Colline Novaresi Nebbiolo Rosé “Rusin” is one of the most consistent and refined, pure Nebbiolo rosés out of Piemonte, and their extremely pretty and upfront 2021 Colline Novaresi Nebbiolo makes these two incredibly good for by-the-glass programs, or when slightly chilled down for a warm summer night when Nebbiolo beckons you but the big hitters are too much. It’s often that I comment with many new arrivals that there are severe limitations, but I am happy to say that we have a good supply of these two wines that should last two or three months—perfect for the second half of the warm season.

We have anticipated the arrival of Ioppa’s 2016 Ghemme for a long time. As mentioned, it was the first year it had Cristiano’s full attention and he and Andrea Ioppa applied some slight adjustments, the smallest of which can change things immensely and up the game. Prior to his arrival Ioppa already made very good and extremely ageable wines but their rusticity and unbridled tannins called for a decade in the cellar before release. Today, those rustic tannins are curbed earlier on, but still the Ioppas are clever enough to hold back their top wines for so long before release. We all know that 2016 was a banner year for Piemonte, especially for Nebbiolo, which makes up 85% of this blend with the remainder 15% Vespolina. After a mere four years of aging in large 25-30hl Slavonian botte, it spends an additional two in bottle prior to release. Their Ghemme cru sites, Santa Fe, composed of a deep clay and alluvial soil, and Balsina, a light mixture of clay with more sandy alluvium deposited by glaciers, are mixed together from a larger portion of younger vines, resulting in a brighter and more vigorous Ghemme than the two single-site bottlings. As always, Ioppa’s top wines need a good aeration before digging in to find their best moments.

Lombardia

Togni Rebaioli, Valcamonica

A two-and-a-half-hour drive east of Alto Piemonte lies Erbanno, the village of the super “natural” winegrower, Enrico Togni (pictured above). One of my new favorites, Enrico dances to the beat of his own drum. To say this, and to add that he’s“a true original” is perhaps a bit cliché, but for some who carry their full meaning, it’s perfectly fitting. A deep lover of nature and animals, he names his sheep and considers them his friends and visits them every morning and night. His verdant, terraced limestone vineyards tucked underneath sheer cliffs are lush with nature from the constant rain, filled with a cornucopia of vines, fruit and nut trees, potato rows, and grains with various garden spots scattered about. He believes that his other agricultural outputs are as important to him as his wines, explaining that as a farmer it’s silly that one should make only wine and no other products, and that once one focuses on a large grape production they move too far away from a healthy, natural ecosystem. But with Enrico and his mostly controlled chaos comes unexpected things, like the first vintage we imported with many labels on the wrong bottles—cases of three different wines with the wrong labels… I knew him personally at that point and the quantity of mislabeled bottles wasn’t enough to create a big problem, and it brought his Loki-esque touch straight to the market, even from afar.

Enrico crafts some of the most delightfully fun and beautifully etched examples of lower alcohol wines with real substance—wines that glide smoothly on the palate but leave the mark of their terroir in the wake of each sip. First to discuss in the batch of new arrivals is his 2019 Vino Rosato “Martina.” Made entirely of Erbanno, a wine considered part of the Lambrusco family (an extremely large and not entirely related umbrella of grape varieties), there is no doubt that it’s one of the most captivating and uniquely complex rosés I have frequently imbibed. During a visit to Enrico’s cellar, some of our staff, JD Plotnick, Tyler Kavanaugh, and I were wowed by the 2020 rosé we tasted out of concrete. For Tyler, it made his top five list of the entire trip, and it made my top fifteen wines of my spring trip covered in last month’s newsletter. A rare rosé worth seeking.

Enrico also makes a regular red wine version of 100% Erbanno labeled as Vino Rosso “San Valentino.” The incoming vintage is 2020, a clearer and finer expression of Erbanno than the 2019. Dark in color but zippy and lightly textured, it's earthy, brambly and woodsy, with foraged dark berries and welcoming green notes. Erbanno, also known as Lambrusco Maestri, has thick dark skin and is very resistant to fungus, a built-in protection needed in this rainy part of the world. Interestingly, Enrico says that it rains more here in the Valcamonica during the summer than the winter.

Last is Enrico’s 2020 Nebbiolo “1703.” I adore Nebbiolo—top billing in the world of grapes for me—and I especially love the ones that don’t knock me out with high alcohol. Enrico’s sits at 13.2%, and it’s the only one of its kind to be found commercially in his area. Enrico found some Nebbiolo in his father’s old vineyard and decided to propagate. Like us (and I mean you, too), he’s infatuated with the variety but also struggles with the rising alcohol levels and easy access to the good ones. He needed some for the house, so he planted. (At the time, he didn’t know what biotypes were but later learned they are lampia, michet and chiavennasca.) Fortunately for us, he has far more than he can drink with his family—including his partner, Cinzia, and their young daughter, Martina, who apparently has the best palate in the house! Valcamonica is a glacial valley with limestone cliffs on one side and volcanic hills on the other. Enrico’s terraced vineyards are on limestone, facing south. The style speaks to this rock type with its full but balanced and elegant mouthfeel, that matches the cooler climate and the green of the countryside. It’s as elegant and subtle as Nebbiolo comes, and highly expressive of its landscape with its cold stone, refreshing demeanor, and all the telltale notes of classic Nebbiolo.