Domaine Christophe et fils

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

In 1999, Sébastien Christophe began to vinify a half hectare of Petit Chablis planted by his grandfather. Since then, he has methodically acquired a multitude of parcels he both owns and rents. He began organic conversion in 2021 but for many years prior, he had already used only organic certified vineyard treatments. All of his vines are located on the Serein River’s right bank (the grand cru side), and all grapes are hand-harvested, spontaneously fermented, go through malolactic fermentation, and are principally aged in steel with less than 10% in oak barrels (new, 1-, 2- and 3-year-old) for the crus and fined and filtered before bottling. The style is classically spare and mineral-driven, resulting in precise and vertical Chablis closer in style to Loire Valley whites than the Côte d'Or.Full Length Story

Sebastien Christophe is our budding superstar from Chablis. We love his wines, but we also love him, the ultimate underdog. While known for its stolid rigidity, France’s wine culture still allows for a lot of mobility. That’s how a young kid gifted just a couple of acres of average vineyard land in Chablis could rise up seemingly out of nowhere to make brilliant wine from the three most heralded Premier Crus in the region. That happened because he was also gifted with a good bit of moxie and a cranking work ethic, which will you get far anywhere. What makes Sebastien’s wines so great? Well, as is the case in Chablis, it’s not the winemaking, which is pretty standard for the region, as the goal here is never to showcase cellar prowess, but rather the nature of the vineyard. Sebastien vinifies and ages wine overwhelmingly in stainless steel, as is the general practice of the region. Less than 10% of the wines see cellar aging in neutral oak barrels, providing a little textural and structural contrast to the bristly energy of stainless steel.

He started with a small half hectare parcel of Petit Chablis from his family and made a run for it. After winemaking school he started to vinify this tiny parcel and has slowly acquired small parcels of village vineyards and a lot of Petit Chablis land. He also rents parcels that he farms entirely himself. Today, he has three premier crus on the right bank of the Serein river, Fourchaume, Mont de Milieu and Montée de Tonnerre. To our surprise, it’s difficult (almost impossible) to find his wines in town on any list. He exports almost everything, save the wines sold to some of the top spots in Paris. Luckily for us, we are the first to work with Christophe in the United States.

Despite nearly unequivocally mentioned in the first breath by sommeliers as one of their favorite wine regions, Chablis often appears in books as the “I guess I should make a little room for Chablis in my Côte d’Or Burgundy bible” category. Indeed it’s not as sexy and elite as the Côte d’Or, but there is a lot to say that doesn’t get said enough. So, while we don’t intend to write an entire book out of this section on our website, perhaps we can bring some ideas not often discussed about Chablis, but relevant to better understand the subject—one that is not so expensive a lesson in understanding terroir compared to that Golden Slope, further south. (Maybe Chablis should consider changing its name to the Côte d’Argent, or maybe the Côte de Platine—a little silver or platinum could be a competitive contrast to the gold.

Chablis winters can be bitterly cold and dry. The lack of snowfall can be deceiving when you’re feeling the bite of the wind, and there are precious few easily found and inviting establishments to duck into and shake off the chill with a warming drink. Its semi-continental climate is similar to Champagne’s to the north, with the winds that whistle in from the North Sea. The frigid air that goes straight to the bone is caused by a relative lack of trees, which fully exposes to the elements, making one of the best refuges to warm up a 50-55°F cellar.

The summers are usually dry and moderate, but that’s all changing. While it’s hard to say what each vintage will bring, the extended forecast is clear: it’s getting hotter. The effects of rising temperatures and increased weather volatility are already felt each season. In many more vintages than the past, the tapering of Chablis’ natural acidic snap is becoming more common. Of course, super fresh vintages still come around, but with record-shattering summer heat happening almost every year, the overall composition of Chablis is, on the average, leaning in a little more toward the soft middle road on vibrancy than the extreme for which it’s known.

Today, (in 2019), frost damange is a commonly occurring antagonist caused by unexpected heat spikes late in some winters. Premature budburst is the new norm, followed by a corrective dip in temperature back to cold leaving the vegetation exposed to frost burn. While frost can take out an entire parcel for the year, it can clip the potential yield of others, exacerbating the problem of quicker ripeness due to the smaller yields with a likely imbalance in the grapes. If you’ve made it out of frost season, then comes the invariably destructive force of hail—a terribly demoralizing event that can happen anytime in the summer. The domino effect of climate change is severe in areas like Chablis, the historical limit of where Chardonnay can ripen consistently for still wine production. Recent vintages in Chablis already demonstrate the heat’s softening of its vertical axis, so they’ve become more rounded and less angular.

A perfect area to exemplify Chardonnay’s merits, Chablis is classified from least to greatest (in theory) from Petit Chablis, Chablis, Premier Cru and Grand Cru, and this is based on three factors: bedrock, exposure and historic reliability. The bedrock isn’t going to change, neither will the exposure, except that the variable of that exposure’s impact will. While I may have painted a painful but honest picture of the forecast, the good news is that within our lifetimes there are less well-known vineyard sites today that maintain the right kind of soil for serious Chablis (although they are likely classified as Chablis AOC wines), but are more protected from the extremes of full exposure to the elements. The last two factors, while assets in the past—like the northwest exposition of the Grand Crus and their ability to be less affected by frost because of that same aspect), may become the liabilities of the future—although no one wants to talk about these things, especially those in the more historically prime spots.

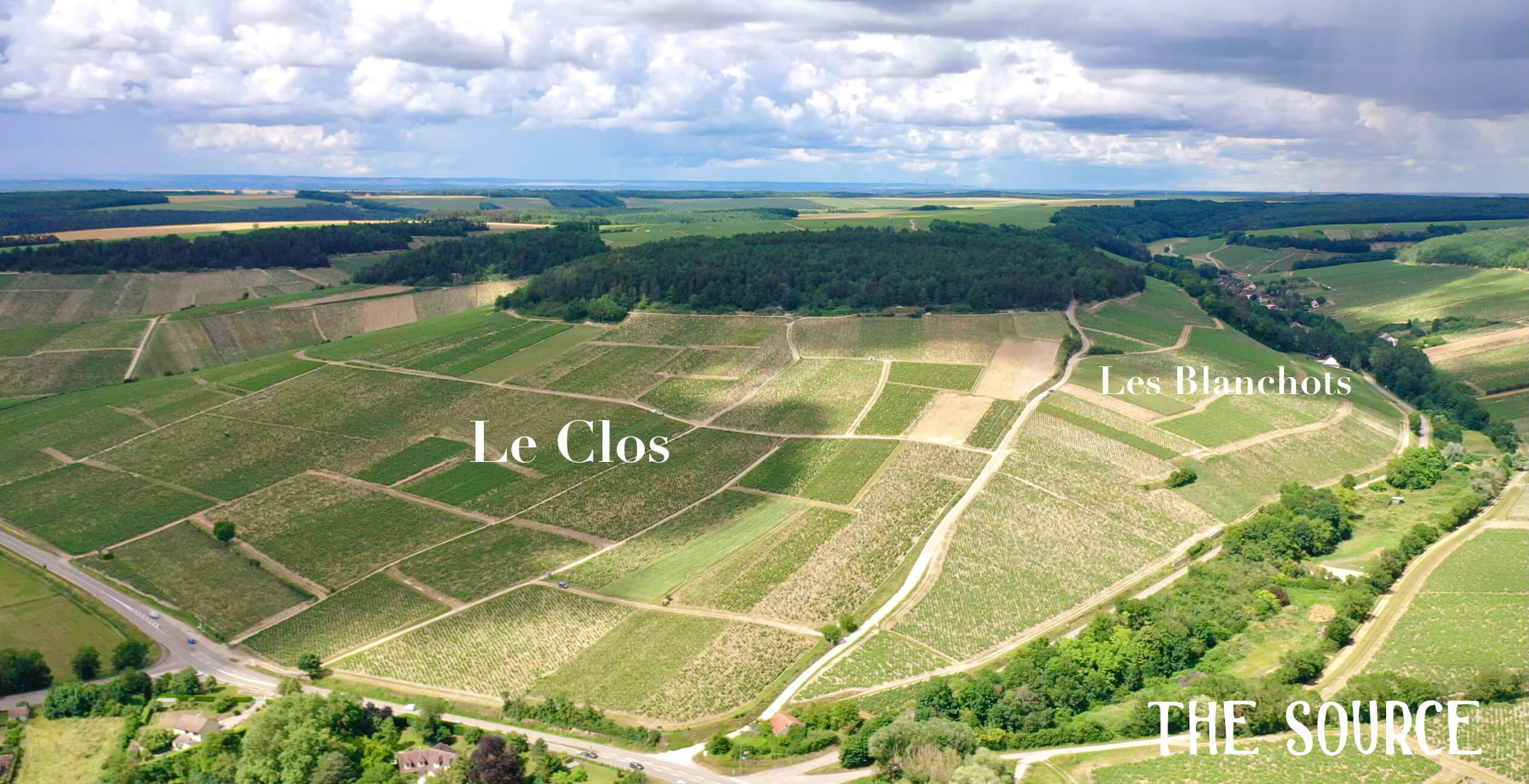

Chablis’ soils are a combination of Kimmeridgian limestone marls and Portlandian limestone scree with various topsoil mixtures of clay and rocks derived from the limestone bedrock—classically Burgundian in general bedrock type and topsoil constitution. These rock formations have influence on the shape of the hills. Those capped with the harder Portlandian rock have more steep, resistant ridges resulting in a more concave hill shape below, like Burgundy’s Côte de Nuits. This deeper inward belly captures more soil such as clay, Portlandian scree and underlying Kimmerigian marls—this is what largely defines the right bank, home to the Grand Crus and much of the fleshy right bank 1er Crus. The hills without a Portlandian limestone cap rock are more convex and maintain less topsoil (mostly on the left bank), similar to the hillslope shape of the Côte de Beaune. Wines on these hill shapes typically have more straight lines, overt mineral nuances and less excess body fat.

As a large generalization, the vast majority of the left bank Chablis 1er Cru vineyards have much less marne (clay and limestone mixture), and a shallower soil depth than those on the right bank. This often results in left bank wines leaning more toward verticality and expressing stony, minerally nuances and textures, while the right bank wines tend to be more corpulent and horizontal (within the context of Chablis, not Chardonnays from further south in Burgundy), with mineral nuances tucked further inside, or simply overshadowed by the denser body. These differences are also somewhat easy to find in Chablis AOC wines or Petit Chablis made exclusively from one side of the river, or the other.

A final thought from our geologist friend, Brenna Quigley, who joined me on a trip to Chablis in 2016: “It’s also important to note that the change from Kimmeridgian to Portlandian is a very transitional one, and can occur over a distance of several meters. Even geologists cannot always agree on clear boundaries between the two—hence some of the arguments over what counts as true Chablis, or true Grand Cru.” -TV

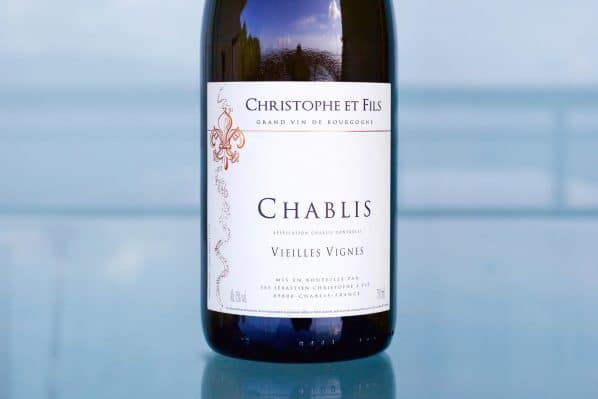

Domaine Christophe et fils - 2023 Chablis, Vieilles Vignes

2 in stock

GROWER OVERVIEW

In 1999, Sébastien Christophe began to vinify a half hectare of Petit Chablis planted by his grandfather. Since then, he has methodically acquired a multitude of parcels he both owns and rents. He began organic conversion in 2021 but for many years prior, he had already used only organic certified vineyard treatments. All of his vines are located on the Serein River’s right bank (the grand cru side), and all grapes are hand-harvested, spontaneously fermented, go through malolactic fermentation, and are principally aged in steel with less than 10% in oak barrels (new, 1-, 2- and 3-year-old) for the crus and fined and filtered before bottling. The style is classically spare and mineral-driven, resulting in precise and vertical Chablis closer in style to Loire Valley whites than the Côte d’Or.

VINEYARD DETAILS

Chablis “Vieille Vignes” is harvested from two parcels replanted in 1959 on steep slopes of Kimmeridgian limestone marl and marne (limestone-rich clay) with an average of 150m altitude in Fontenay-prés-Chablis, with one parcel above 1er Cru Fontenay and the other southeast of the village center with west and north expositions, respectively.

CELLAR NOTES

Hand harvested, pressed, and settled overnight, then racked off heavy sediments before undergoing a slow, low temperature, natural fermentation over 1-2 months prior to a year of aging in 85-90% steel and 10-15% in old 228L oak barrels (5-6 years old) with an occasional bâttonage, if needed. Prior to bottling it’s fined and filtered.