One of the obvious requirements of being a wine importer is that you really need to know as much as possible about the wines you import, the regions they come from, and who’s who in the region—especially if your principal customers are the top culinary restaurants and fine wine retail shops in the US. I knew next to nothing about Iberian wine five years ago, but I’ve been determined to learn as much as I can and have benefited greatly from the experience of people in the industry who paved the way in this landscape long before me. My preoccupation with preparation has pushed me deep into the two Iberian countries where we are now focusing much of our attention.

Through the process of trying to catch up on these regions I hadn’t really noticed over the last fifteen years, I began to create educational material for my coworkers at The Source to pass on to our buyers. Shortly after starting this compilation, I realized that there was a serious shortage of really useful information on these areas so that many of our customers could connect the dots as well. A basic list for the new additions to our producer roster, including general data, vinifications and terroir overview in bullet-point format extracted directly from the growers would’ve been easy, but such oversimplification would have left too much unsaid. As is common when seeking answers about wine (and life), each path led to endless opportunities for learning and lessons in humility.

This insatiable curiosity led me to embark on a year-and-a-half long terroir map project with the young University of Vigo MSc Geologist and PhD student, Ivan Rodriguez, and my wife, Andrea Arredondo, a Chilean whose career focus has been on graphics and web design. The first series includes seven maps with details on climate, grape varieties, topography and geology. On the list so far are Portugal’s Douro, Vinho Verde and Trás-os-Montes regions, as well as Spain’s Jamuz, Bierzo, Valdeorras, Ribeira Sacra, Ribeiro, Arribes, Monterrei and Rías Baixas. Our general focus will mostly be on regions that are currently less well-covered.

I put out a teaser in our April newsletter for our Trás-os-Montes map, but the first official release will be the map of Ribeira Sacra, along with a relatively extensive essay on the region that I researched and wrote last year. The text is based more on my own findings than from other printed or web resources in the way of input from local vignerons and highly-involved and knowledgeable restaurant professionals. The most notable source from this last category aside from a group of vignerons, was Miguel Anxo Besada, a complete insider and the owner of two restaurants, A Curva and Casa Aurora, located in the coastal Galician towns of Portonovo and Sanxenxo.

Miguel is a sort of guru in Galicia, a sounding board where local growers can bounce ideas to help them develop global perspectives. There are others with whom I’ve spent time with as well, such as Fernando and Adrián, from Bagos, in Pontevedra, who wield tremendous influence by way of their extensive global wine lists and their strong desire to share and spread the word on good work from any region. And I absolutely must include the globe-trotting duo from Bar Berberecho, José and Eva, who have a medium-sized but very well-curated list.

I met Miguel on my second trip to Galicia and wanted to go back to soak up what he had to say about a number of the great wines from the top producers there. After he opened a full case of wine for us to taste, he refused to give me the bill for them or the dinner! That’s what it’s often like with the crew in Galicia. These maps and our work to support the winegrowers we import along with the rest of the entire region’s wine community are the fruits of my travels here, and my hope is that I can be helpful in spreading the word and clarifying a few things about the region.

The well-known former sommelier, winery and restaurant owner, Kevin O’Connor, has joined The Source. Kevin and I worked together at Spago Beverly Hills back in the early 2000s where he initially assisted the late Master Sommelier, Michael Bonaccorsi, and eventually took over the program for many years. During his time at Spago he started a winery with Matt Lickliter called LIOCO, and after he moved on from there he returned to the restaurant arena for a while, but has now signed on with us as our National Sales Manager, among many other things that he is well equipped to do, what with his deep experience in the industry. We are lucky to have him on board.

We have another fabulous new addition with Australian former sommelier and wine buyer, Tyler Kavanagh. Tyler worked for numerous spots in California, most recently at San Francisco’s extremely well-curated, Italo-centric program at the wine shop, Biondivino. I’ve known Tyler for nearly seven years as he moved through various spots in California from San Diego, Tahoe, Santa Barbara, and San Francisco. I’ve always been interested in working with him because of his extremely friendly demeanor and thoughtful approach to wine. He will be holding the post as our wholesale sales representative in San Diego and Orange County—lucky for us and for the buyers in those markets!

Pierre Morey’s 2018s will be available at the beginning of July. As mentioned in a previous newsletter, 2018 is a wonderful vintage for Chardonnay. The white Burgundies I’ve had so far from that year have been a great surprise. I recently had dinner in Staufen im Breisgau, Germany, with Alex Götze, from Wasenhaus, who used to be a cellar hand at Domaine Pierre Morey for quite a few years. We opened a bottle of 2014 Meursault Tessons and talked about Morey’s wines and how their typical path after opening starts with a concentrated wine that after an hour or more it opens remarkably and rewards the patient drinker. Layer after layer of finely-etched minerally nuances and palate textures begin to slowly overtake the more structured elements that are initially dominant. 2014 is obviously a very good white Burgundy vintage and this wine direct from the domaine didn’t disappoint.

David Moreau continues his upward climb within his Santenay vineyards. Santenay is not an appellation one thinks of immediately when they think about Burgundy, but it says something that it used to be the home of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti and there has to be a good historical reason for this. So maybe it’s time to check out a wine from one of the top producers in the appellation. David’s wines lead with aromatic earth notes and fruit as a secondary and tertiary element, which, for me, makes them the ideal type of Burgundy with food. My tasting with him in the cellar last week showed once again that he’s still on the rise.

It’s been too long of a long dry spell with regard to our stock of wines from Thierry Richoux. If you ever came to my house in Santa Barbara before I moved to Europe, you’d know how regularly I drink his wines, because I truly love them. The 2015 Irancy Veaupessiot and the 2016 and 2017 Irancy appellation wines are about to arrive. The 2016 is deeper and perhaps more concentrated because of the extremely low yields, while the 2017 is perhaps brighter and more ethereal than any Irancy I’ve had from Richoux before, an influence no doubt from his two boys, Félix and Gavin. These young and very cool dudes are taking the domaine in a slightly different direction. Their approach is a lighter touch with the extraction, more stems and more medium-sized oak barrels (as opposed to mostly foudre) for the vineyard designated wines, lower SO2s and with a later first addition—all common in today’s global movement of many small, sulfur-conscious winegrowers. Nothing of this offering is to be missed, especially the 2015 Veaupessiot, perhaps the most compelling wine yet bottled at this extremely talented Burgundy domaine that has developed a strong cult-like following in recent decades, and a very long history with private customers from Paris who drop into his tiny village on weekends and scoop up as much of his product as they can.

Anthony Thevenet is staying his course in producing a more substantial style of Beaujolais while maintaining high aromatic tones. It’s impossible for Anthony to make completely ethereal wines because much of his range is from one of the deepest stables of old vine vineyards in the region, which naturally means huge complexity potential but a touch more ripeness and concentration. I’m not sure of the average age of his family’s vines, but they are all very old—the eldest planted around the time of the American Civil War. We brought in the 2018 Morgon and Chenas appellation wines, and the 2019 Morgon Vieille Vignes from 85-155 year-old vines, and the 2019 Morgon Côte de Py “Cuvée Julia” from 90 year-old vines and named after his daughter. All are worthwhile considerations, but the latter two wines in particular shouldn’t be overlooked, especially for anyone interested in a little exercise in terroir soil and bedrock comparisons: both wines are made exactly the same way in the cellar with the Morgon V.V. grown purely on granite bedrock, gravel and sand, and the Morgon CdP on an extremely hard metamorphic bedrock and a thin layer of rocky topsoil. They’re both impressive, especially in 2019 with all their bright red tones.

Some other goodies landing soon are Corsica’s Clos Fornelli and the Rhône Valley’s Domaine la Roubine. Clos Fornelli is one of our fastest-selling wines, so don’t wait on those. They offer stellar value out of Corsica and they’re such a pleasure to drink. We don’t talk too much about La Roubine because there are loyalists who typically snatch these wines up as soon as they arrive. Sophie and Eric from La Roubine make small amounts of Sablet, Seguret, Vacqueras, and Gigondas, and their wines have been notably absent over a couple of vintages because we’ve missed our opportunities to procure some. Their organically grown grapes, certified as such in 2000, are all whole-bunch fermented for at least a month in concrete and up to forty-five days with the top wines in the range. Tightly wound (a good thing for Southern Rhône wines) and without a hair out of place, they’re also chock-full of personality and emotion.

It’s great to be on the road again in the more familiar territories of Italy, Austria, Germany, and France. I’ve been so focused on and excited with what’s coming out of Iberia and what luck we’ve had curating a collection of producers there that I can’t seem to get enough of. My wife and I drink wine every day with dinner, but these days, when it comes to reds, we often opt for wines from our neighborhood of Galicia and Northern Portugal with low to moderate alcohol levels. Unlike with Iberian wine regions, there seems to be less territory to “discover” (or rediscover) from a terroir perspective in countries like France, where the new ground seems to mostly be in exploring different cellar techniques.

Finding new things in Iberia gives me the same feeling of joy as when you I someone who has some ordinary job walks onstage on one of those TV talent shows and within seconds makes my jaw drop as a small tear wells in my eye because I’m just so damned happy to watch an unknown talent emerge onto the world stage right in front of my eyes. New wines from deeply complex, multi-faceted terroirs seem to pop up every other week in Iberia, often with the reworking of a patch of land abandoned by a family one or two generations ago. It’s exciting, and the infectious energy of the winegrowers has influenced me to sink a ton of my energy in their direction for many years now. I get an adrenaline rush from this place and it has increased my already uncontrollable enthusiasm for wine.

On the docket is a small batch of Ribeira Sacra wines from Fazenda Prádio and Adega Saíñas, the long-awaited arrival of Cume do Avia’s 2019 Caíño Longo (along with more from them), Manuel Moldes’s Albariño “As Dunas,” grown on pure, extremely fine-grained sandy schist soil, and César Fernandez’s “Carremolino,” a red wine blend from Ribera del Duero from pre-phylloxera vines and others planted more than eighty years ago. There is so much to say about each of these wines and there will be a lot of information coming down the pipeline throughout the month.

In the first eight years of our company’s existence, we brokered a couple of Italian wine import portfolios in California and fell behind on that front as an importer. After parting ways with the last of the importers, importing Italian wines directly starting five years ago was slow going because importer competition in Italy had already reached a fevered pace, what with the exploding popularity of the backcountry, indigenous wines that appeared center stage on progressive wine lists about a decade ago. Social media’s influence has been a huge part of this because it opens opportunities to completely unknown growers who sometimes become world famous in a very short time. The good news is that the people we’ve found with the help of our many sources (the true origin of our company’s name) have yielded some fabulous opportunities.

We start this month with Basilicata’s Madonna delle Grazie and one of their top Aglianico del Vulture wines, Bauccio. Every call with the family winemaker Paolo Latorraca (and there are many) ends up in a conversation about Bauccio; they’re obsessed with it and I understand why. It’s one of two wines they produce only in the best years when there’s an even longer growing season in what is already one of the world’s latest regions to harvest grapes for still wines. It comes from their finest, old-vine parcels and it’s a steal for the quality and price. It’s very serious vin de garde and drinks amazingly well now too. The new release is the 2015, a spectacular vintage with perfect maturity, balanced structure, full volcanic dirt textures on the palate, and gobs of flavor—well-measured gobs, but gobs nonetheless. The soil here is black volcanic clay mixed with blond, soft, sandy volcanic tuff rock uplifted from the bedrock below, and the genetic material from ancient Aglianico biotypes originating from the region tie it all together. Their entry-level Aglianicos, the Messer Oto and Liscone, are getting restocked as well. These two are in constant demand and represent as good as we have for serious wine, at an approachable price for the everyday-wine budget.

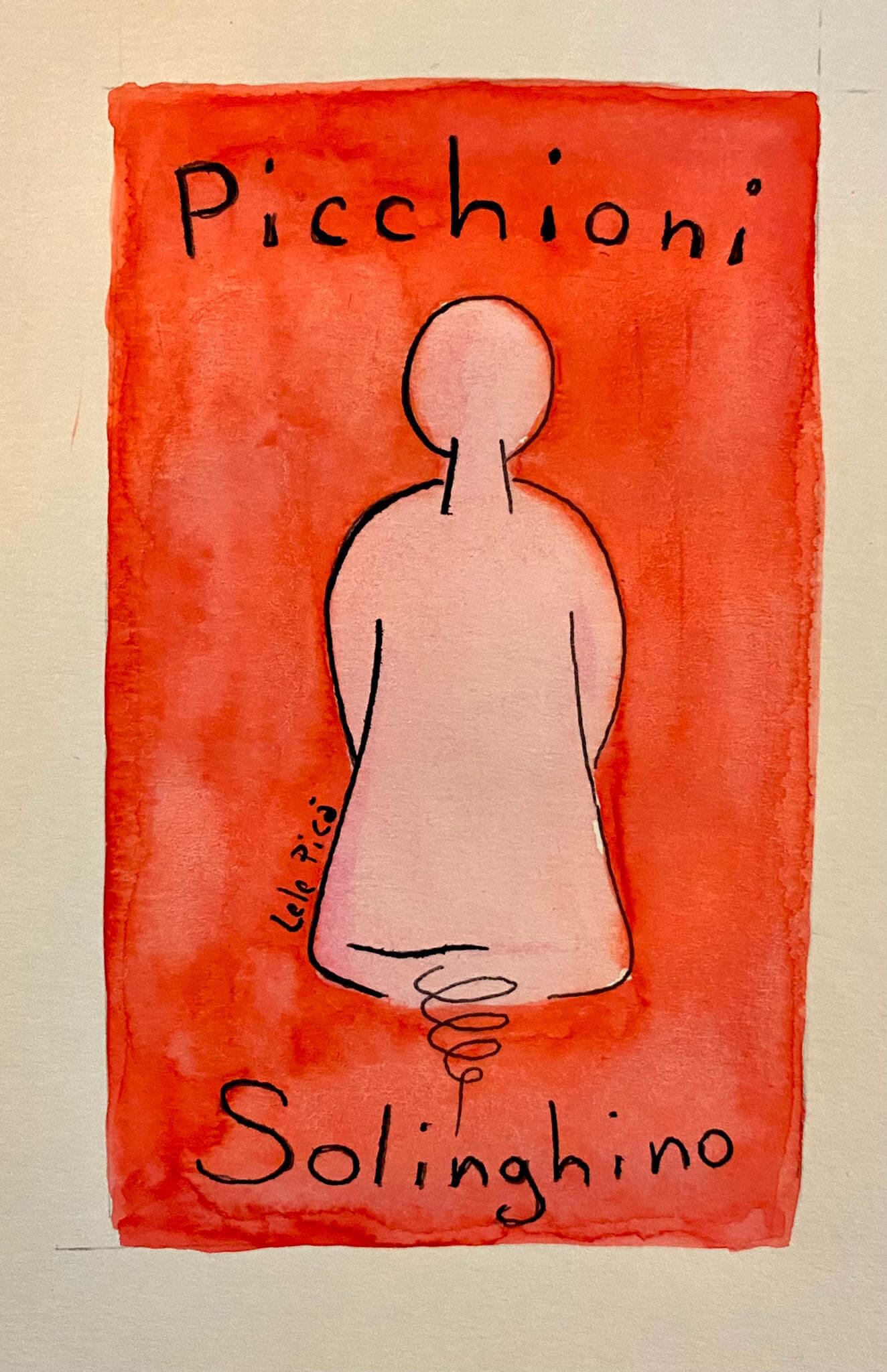

A couple of years ago in Andrea Picchioni’s tasting room, I saw a label that immediately grabbed my attention, a one-off for a special cuvée from years ago. I asked if he would consider putting the same label on the wine he calls Cerasa, a delicious Buttafuoco dell’Oltrepò Pavese with more solemn graphics that contrasted the pure joy and generous flavor inside the bottle. Without more than a second of thought, he agreed to the change and also changed the wine’s name to Solighino, a reference to the valley where his vineyards are located. Just look at that label now! It’s beautiful, and you will see when you taste it that it reflects the wine itself. We will also get a micro-quantity of his top wines that are soon to become culty collector wines, Rosso d’Asia and Bricco Riva Bianca. People who are crazy about Lino Maga should pay some attention to this guy. Italians in Italy, who know Andrea and his wines, say that he is Lino’s spiritual heir. His wines find the same level of x-factor as Lino’s, which come from vineyards quite literally just over the hill from Andrea’s, even though Andrea’s are not as rustic.

In Alto Piemonte, Fabio Zambolin continues to capture pure beauty with his Nebbiolo vineyards planted on volcanic sea sand. His Costa della Sesia Nebbiolo (actually grown entirely within the Lessona appellation, but it can’t carry the appellation name due to the cantina’s location just a few meters outside of the appellation lines) is simply gorgeous and always a treat. Unexpectedly, Feldo, his blended wine composed of 50% Nebbiolo along with equal parts of Vespolina and Croatina grown just next to one of the vineyards he uses for the Nebbiolo wine, jumped a few full notches with the 2018 vintage. A month ago, when I tasted it in the cellar for the first time, I was almost speechless (yes, I know that’s hard to believe for anyone who knows me) because it may as well have been a completely different wine from any of the past vintages. It seemed like more of a special cuvée-type wine even though it’s still just a Feldo.

I love what all of the growers in our portfolio have to offer. Some are less experienced but still make very honest and pure wines that clearly speak the dialect of their region, while others don’t fit into anyone’s box but there’s nothing off putting about the space they occupy. That’s Mauro Spertino. Mauro, who I fondly refer to as our “alchemist,” is simply one of the most creative minds in wine that I have come across. He makes a range of completely unique wines that all carry the hallmark of his gorgeous craftsmanship and completely authentic persona. Perhaps Mauro’s success and openness to try new things can be partially credited to the fact that he is in Asti rather than Barolo or Barbaresco. Asti is a region with nearly no expectations other than its low price ceiling.

Only two of the wines within his range are hitting our shores on this container: Grignolino d’Asti, a wine that redefines this category and has already become a cult favorite for those who’ve had it, and Barbera d’Asti La Grisa, an unusually elegant but concentrated Barbera that is much more substantial than expected. Led by the variety’s naturally high acidity and low tannins, Mauro finds a way to weave in an unexpectedly refined, chalky texture into La Grisa, with a sleek and refreshingly cool mouthfeel. Later this year, we will have his Cortese orange wine (a smart move on making that grape orange), zero dosage Blanc de Noir bubbles made entirely from Pinot Noir on calcareous sands (of which I bought a six pack to share with our winegrowers along the route I’m currently on in Europe), and his amphora-aged Grignolino, another redefining wine for this grape and totally different from the other one in his range.

Sadly, a few days before my recent arrival to Mauro’s cantina, his father, Luigi, passed away. Luckily for many of us at The Source, we were making our way through Piemonte the week the pandemic took hold of Milano in late January/early February of 2020. After our visit with Mauro, we asked to meet Luigi; this, of course, was before we understood how serious the pandemic was and how vulnerable the elderly would be. He extended his large, soft hands for a shake—the hands of a retired winegrower—and he seemed as thrilled to meet us all as we did him. Knowing that it would be a rare and possibly unrepeatable opportunity, I snapped a few quick photos that may have been some of his last. I knew him for only a few minutes, but when you have the pleasure of knowing his son Mauro and his two grandkids, it’s easy to deduce that he was a great man.

At first, I thought it was a little crazy to drive alone from Portugal to as far as Burgenland, Austria, and back home after six weeks of winery visits, but after I got past the long haul through Spain and into France it seemed like maybe I should do it this way every year; I felt freer than I ever have on the wine trail. I packed my pillow (which I unfortunately left at a hotel in Germany three weeks in), a picnic basket full of useful silverware and kitchen knives (not one AirBnB will provide you with a decent knife, even if the kitchen is fabulous), a microplane (I’m obsessed with lemon zest these past few years), oats and nuts, Portuguese canned sardines, corn nuts, Snickers bars (most of which are melted now because it’s been hot!), a drying rack for my clothes, foam roller, yoga mat, a few small weights, a huge pile of Zyrtec pills (it’s high allergy season in June and I promised myself that I wouldn’t travel anymore in June because they are so intense at this time, but I threw that one out of the window because it’s been too long since I made my rounds). I have bags full of photography, video, drone, and sound equipment that seem far too heavy now to get past even the carry-on checkpoint and into the overhead compartments on a plane. Maybe I could get a camper and hit the road in comfort and take my time. It seems like an interesting way to live and I’m sure it would be a lot of fun to do it that way at least a couple of times. You know, #vanlife, but with wine as the guide and the destination. Three weeks after I started to consider this option, my wife called. I thought she had no idea what was going through my mind, but it turned out that I think she somehow suspected. She asked if it was my plan to keep doing it this way moving forward, and the tone of her interrogation changed in a way that I immediately decided it would be best to forget the idea. At least for now.

I’ve played the band London Grammar more than any others since I’ve been on the road. Their music, led by the intimate and deeply emotional voice of Hannah Reid, keeps me in a pleasant dreamstate as I develop ideas while staring out the windshield on the long legs of the trip. I mentioned in last month’s newsletter that there were a number of songs my mom used to play when we were on the road when I was a kid, but I never expected that while having breakfast this morning at the Malat’s hotel in Austria’s Kremstal region that Michael’s mom, Wilma (who cooks the best omelets: soft, partially runny, perfect eggs with streaks of the dark orange yolks not completely blended with the whites, asparagus, tiny carrot cubes, and thin and tender cured skillet-fried pork) to put an old Neil Diamond album on their record player. He was one of my mom’s favorites and it occurred to me that Austrian and Iowan moms are not as different as I would have thought. As I fully indulged in their ridiculous breakfast spread (I mean, who serves sautéed chanterelle mushrooms in a buffet style breakfast? The Malats do, that’s who), I never realized until that moment how intense and almost urgent the tempo of a lot of Diamond’s songs feel. I suppose that kept my mom up on those non-stop overnight road trips from Montana to Iowa.

On this trip, everything from everyone tastes better than I remember almost any of their wines tasting out of barrel and tank, and I have to remind myself that it’s not just because I was cooped up like everyone else for twelve of the last eighteen months; the world of wine is simply getting that much better from vintage to vintage. It could be that the wines are emerging out of their winter slumber, and like us, they are smiling and feeling more comfortable with the energy and warmth of spring and early summer.

I usually tour in the fall, winter and early spring because the summer is often too difficult; it’s tourist season and hotels and restaurants are all booked or unreasonably priced for what you get. But as the world is still recovering, traffic is lighter than normal right now, and I’m taking advantage of that.

I’m just a short drive across the border from Alsace. It’s mid-June, but it’s so cool that it feels like the last week of May. Grape season started late this year after a cold and frosty spring brought disaster to the many crops in Europe. The vines were hit hard, but so were many other plants, such as the apricots in Southern France. Two days ago when I was at Weingut Wechsler, a new producer for us in Germany’s Rheinhessen, they said that over the last week the weather changed from cold to hot in a twenty-four hour period. The vine shoots have been growing more than three centimeters a day over the last week now, so fast that it’s like you can stand there and see it happening. The same thing seems to be going on everywhere.

I started off this long trip by passing through Douro, in Portugal, and on into Tràs-os-Montes, the country’s most northeastern region, a place that gave me a lot to think about. I stared off into its colorful high-desert landscape covered in oak trees, bright yellow mustard-tipped shrubs that extend at least all the way to Austria, then drove through small canyons of multicolored slate walls carved through low hills in order to make some parts of the highway a straight shot. I usually travel with one or two or a few people (that sometimes rotate out to be replaced by others), but this time I’m alone on the road for more than five weeks, before my wife, Andrea, joins me in Provence on the first of July. At other times I often find myself corralling a group, organizing accommodations, talking to my companions the entire time in the car (don’t get me started on wine, obviously), and making sure they are getting the most out of the experience. I had almost forgotten how to be alone on the road. This year, Andrea was in Chile for a month in January and stayed an extra month because she had an opportunity to get vaccinated there. So I was alone in Portugal for two months during the pandemic, which turned out to be perfectly fine. In fact, I really enjoyed it. I did a lot of things I’ve been meaning to do for some time, a two-week juice fast, read a ton of books (absolutely devoured Matt Goulding’s works on travel and food), dug in on Spanish five days a week with my new teacher and now friend, Fabiola, did more research on wine and science, and wrote a lot. Trying to look on the bright side of things, I’d like to say I did the best I could to make it a personally enriching pandemic.

I didn’t spend that much time in France visiting producers on my way to Italy. I stopped by to visit a guy in the southwest who has agreed to work with us, but after learning the lesson about counting unhatched chickens the hard way, I decided to keep the details of who he is to myself until we actually have his wine on the boat, because things sometimes take unexpected turns.

La Fabrique, the French countryside home of my dear friends, Pierre and Sonya, was even more on point than ever. Sonya retired a couple of years ago and she’s gone mad in the kitchen, cooking feasts for a party of two during the pandemic, as shown on her social media posts. We had white asparagus for days, served with Pierre’s perfect mousseline, late spring and early summer delicate vegetables, heavily anchovy-dressed red leaf lettuce (my original favorite salad), cherries, (apricots were sorely missed after being almost completely lost to frost this year). They were massive and overindulgent lunches and dinners with Sonya’s unstoppably evil deserts. The problem? I couldn’t run outside to burn it off because the allergies this year are especially horrible because of the late cold and very wet spring, so I definitely gained some weight. The day before I left La Fabrique Sonya and I went to an uncultivated field to pick wild thyme that is now drying at her place, waiting for my return at the beginning of July.

The next day I left to visit Stéphane Rousset and his wife, Isabelle. As mentioned in last month’s newsletter, they’re doing a new bottling, labeled Les Méjans, and it’s exciting wine. I also asked them to put the vineyard name on their Saint-Joseph, which they said they’ll do; having just Saint-Joseph or Crozes-Hermitage without much else on the label isn’t helpful considering the tremendous diversity of terroirs with very different soil types and exposures there, even if the reds are entirely made from Syrah, and the whites a blend of Marsanne and/or Roussanne.

I passed through Savoie after my visit with the Roussets for a night with my friends, also in the wine distribution business in France, Nico Rebut and his wife, Laetitia. The next morning I passed through the Fréjus tunnel into Piemonte with no one waiting at the border to see the negative Covid test I was ready to proudly produce. I wasn’t surprised. It’s Italy…

I visited our four producers in Alto Piemonte, and hung out with my friend of ten years (time is flying!), Cristiano Garella, a well-known enologist in the area. And I had nice meetings with Andrea Monti Perini, in Bramaterra, with his crazy-good Nebbiolo-based wines out of wood vats. As mentioned earlier in this newsletter, Fabio Zambolin knocked it out of the park with the 2018 vintage. The changes the guys over at Ioppa have made in recent years are finally coming to the market. Their 2016s are impressive, and the 2015s are right there with them, but they’ve recently really gotten a more measured hold on the tannins and texture of the Ghemme wines. The biggest surprise in my tasting at Ioppa was the 2016 Vespolina “Mauletta.” I’m almost sure that it’s the best example of a pure Vespolina wine I’ve had, except perhaps the Vespolinas from the newest addition in the portfolio, Davide Carlone. I made the visit to Davide with Cristiano and we tasted through a bunch of wines in vat from different Nebbiolo clones that are vinified separately, and what an enlightening experience that was. The differences between clones is much greater than I expected. We don’t talk about genetic material so much in old world wines as we do with the US and probably the rest of the “New World” wine regions, but we should. It greatly impacts the wine.

After Alto Piemonte, I dropped down to Langhe and crashed at Dave Fletcher’s train station turned home-and-cantina. I love this place. Dave said that before he started the process to buy it from the city, no one else was interested in it. His friends said he was crazy, but when word got out that he was serious, the interest increased, and Dave had to hustle to get his name on the title before he was wedged out. They live in a sort of dreamworld inside that old station; when I’m in it I imagine the antique setting and how so many people passed through it long ago; it’s beautiful, and almost joyfully haunted by their spirits. Dave and Eleanor (Elle), his wife, wisely kept most of the interior space the same, with the ticket counters and the coffee and wine bar. I took full advantage of the opportunity to cook so as to control my food intake, which completely backfired because I think I ate even more food there than I would’ve in restaurants along the way. We enjoyed lamb on the barby (said with Dave’s Australian accent), marinated with anchovy, garlic and some of the French thyme from our friend’s place in Provence, and I turned Elle on to high quality canned anchovies from Cantabria (which she never liked before) and salt-packed ones from Sicily on top of cold, salted butter and fresh bread with a paper thin slice of garlic, dried oregano, lemon zest and a little red pepper—a recipe I picked up from Aqua Pazza, a fabulous restaurant in the Amalfi Coast’s truest Italian fishing village (where residence actually live and work all year round), Cetara. It was exactly what I needed after a week straight of decadent eating on the road.

I met the Collas for lunch at their house up in Rodello, a beautiful village that sits on a long, narrow ridge well above the cold and fog of Alba. On a clear day at their house, you can see the Alps perfectly to the west and north, the Ligurian range to the south and to the east and the northernmost expanse of the Apennine Mountains, which from there run all the way down to Sicily. Bruna, Tino Colla’s wife, makes fresh pasta in a room for doing just that, next to their small cellar, which is loaded with antique wines that Tino has stashed for more than fifty years. This treasure is hidden below the main floor of their four-story house that sits on the top of the hill, situated above all the other homes with just the nearby church blocking a small slice of the view. The cellar is filled with a lot of old wines from the Colla’s Prunotto days and from Cascina del Drago, an estate that covers the better part of a hill, just on the border of Barbaresco, where Beppe Colla used to make the wine and which the Collas ended up buying from the previous owners who insisted that they would only sell it to his family. While our team was on tour in Piemonte when the pandemic first hit Italy, Tino opened up a series of old, irreplaceable Prunotto wines (1980 Barolo Bussia, 1978 Barbaresco Montestefano, and 1968 Barbera) and a red from Cascina del Drago, a Dolcetto wine with fifteen percent Nebbiolo, stole the show. It was a 1970, and it virtually crushed the field of already fabulous old wines. Cascina del Drago is a story that needs to be told because it is an unusual historical wine made from exactly the same blend of grapes from that hill for generations (long before the IGT blended wines were a thing), but the best way to understand it is to taste old bottles. They seem to be indestructible, easily competing for the top position in any range of old Piemontese wines they come up against. Yes, they can be really that good.

One of the unexpected highlights of my time with the Collas came in the form of a unforgettable vinegar for a simple, greenleaf salad Bruna made to accompany the zucchini flan, carne cruda di fassone buttuta al coltello (knife-cut beef tartar), salsiccia di Bra, a small raw beef sausage made only in Bra (it’s so wonderful, and also a leap of faith considering it’s raw sausage, but the butchers have done it cleanly with all of those I’ve had so far), and a Bruna-made fresh pasta, tajarin con sugo di carne e funghi, a very thin, flat pasta that takes literally one minute to cook and serve with a meat and mushroom tomato sauce that takes nearly a day of cooking to find the right consistency. This vinegar is the continuation of a vinegar mother started in 1930, a profound experience that they’ve been topping up with mostly Nebbiolo over the years. I asked for a bottle and Tino looked at me as though I asked to be written into the family will for an equal portion of the estate. Sometimes in life you simply need to ask for what you want and you will get it. It would have been an audacious ask if it were anyone but the Collas, but they are like family to me, and I think they often feel the same way.

After a weekend intended to be a respite from excesses of food and wine that turned into a full-blown cooking-and-drinking fest at Dave’s station, I reluctantly left their warm hospitality and headed toward Asti for a morning visit with a cantina whose wines I briefly sold about ten years ago in Los Angeles for one of the Italian wine importers I used to work with. La Casaccia is located in Cella Monte, a village in the Monferrato area of Asti, and is run by Elena, Giovanni and their kids, Margherita and Marcello. Upon my arrival I was greeted by Margherita, a woman in her early thirties who looks barely a shade over twenty, with a big and welcoming smile and an extremely comforting demeanor. She proposed a walk through the vineyards, then a tasting and lunch. Little did I know that many of their vineyards are surrounded by wild cherry trees that were ready for picking. In their vineyard that makes the Barbera, Bricco dei Boschi, Margherita pointed to a tree and said that they were probably too sour still. I picked a cherry anyway and gave it a try. It was one particular cherry tree intertwined with others near the top of the vineyard. The first cherry exploded with flavor and aromatic complexity, like a great Mosel Kabinett Riesling. I couldn’t stop eating them, nor could Margherita. Small, with delicate skins colored from light red to pink to orange and yellow all on the same cherry, I know that they were the most incredible cherries I’ve ever had. The acidity was through the roof, as was the sugar. The only other fruit comparison I can think of is a perfectly ripe and ready to pick white wine grape. It smelled and tasted like a mixture of rieslings from JJ Prum and Veyder-Malberg. Should I have a better cherry in my life, it would be an unexpected surprise.

After our walk through the vineyard with conversations about their family and other non-wine things, like yoga, vegetarianism and the organic life (not just organic vineyards), she felt so familiar, like we’d been friends for years. The weather was overcast, slightly warm and lightly humid, just perfect for an outdoor tasting and lunch. After working through Giovanni’s range of authentic and emotion-filled reds (most notably the entry-level Grignolino, Freisa and Barbera wines) and a racy, undeniably delicious stainless-steel raised, vigorous limestone terroir monster of a Chardonnay grown on their pure chalk soil (think: a trim Saint-Aubin sans oak aging but dense in that limestone magic along with the exuberance imparted by a fanatical, fun and quirky winemaker), we sat for a lunch prepared by Elena. It started with an egg and vegetable tart, followed by fresh cheese-stuffed raviolis made by a well-known local pasta maker just a few villages away who used to own a restaurant known for excellent pasta. He has since closed it to focus only on pasta making—lucky for everyone in the region because these raviolis were special. Next stop, Spertino.

I could contemplate and try to write about Mauro Spertino’s wines all day, but the only descriptions of what he renders with each wine that would truly do them justice would be in poetry, a skill that I haven’t even attempted to develop. Bottled under his late father’s name, Luigi Spertino, all are almost completely different from other wines around him—perhaps not only in Asti, but in all of Italy, or even the world. He lives in a middle of nowhere part of Piemonte, but in his lovingly rich family surroundings he finds what appears to be the same inspiration and genius-level creativity found in the countryside by many former city-dwelling Impressionists of the late 1800s; his ability to imagine and realize his dreams in liquid form is that rare. I imagine him lying awake at night staring into the dark thinking about how he should move a hair here and a hair there to next time outdo the marvel (at least for me) that he has just put the finishing touches on and bottled.

In this July newsletter, I’ve written more about Mauro and the wines I tasted during my visit. It was truly inspiring, and if I should classify the wines we work with on artistic flair and originality, his are so far out of the box and perfectly tuned that I may have to consider him to be one of the most important in our portfolio.

Next stop was with the Russo brothers in northwest Asti, Federico, and the twins, Marcello and Corrado. I always seem to be in a rush when I see these guys and I often feel like I’ve missed something they wanted to share with me, or show me. Maybe it’s just that they have so much to share. They are as generous in spirit vis-à-vis food and drink as anyone I know, and spending just an afternoon, evening and the following morning once a year never seems like enough.

When I arrived to visit them it was already late. An early summer storm was imminent and I wanted to get some drone footage of their vineyards while there was a dash of sunlight and a pregame of drizzle in the air before the downpour. I didn’t want footage from up high because Crotin’s are not particularly exciting vineyards; I wanted to show how they are different from most of the region because their vineyards have mostly recovered from the abandonment that began after the last of the great wars. They are some of the closest Asti vineyards to Torino, so they are some of the last to be recovered. Their vineyards are surrounded by wild forests, open pastures, and diverse agricultural fields, mostly hazelnut and fruit trees, which all seems to be felt in their lively wines. What I thought would be some easy shots of flat vineyards ended up with me taking a twenty minute drive to look at a new Nebbiolo vineyard that sits around 480 meters (higher than Giacomo Conterno’s Cascina Francia vineyard in Serralunga d’Alba, for example), on white, calcareous sands with blue-grey marl. The vineyard is spectacular and not at all flat, and their desire is to produce a wine from it that should be drunk younger, a sort of equivalent in style to a Langhe Nebbiolo raised in steel. Regardless, I expect a very special wine from this vineyard, especially with the mind of one of the world’s most talented young Nebbiolo whisperers, enologist Cristiano Garella, as a strong influence. Exciting!

Next Newsletter it’s a continuation of my loop around the Alps through Italy’s Lombardia and Sudtirol, then up into Austria and over to Germany en route back to Champagne and Burgundy. Ciao for now.