Masson took us to his production building and gestured quickly at his variety of medium-sized wine tanks (none of his wines are vinified or aged in oak barrels) before leading us into his cellar, a dark, ground-level little room adjacent to the one with all the equipment. The walls were roughly spackled, with rounded corners to the ceiling, giving a quick impression of being inside a dimly lit cave.

The space was almost entirely filled with unlabeled bottles stacked like firewood. Aluminum cages were packed with yet more bottles, and sloppily stacked wooden crates and empty cardboard boxes lay in scattered piles. It was a gritty and utilitarian atmosphere for tasting fine wines, yet somehow at the same time exceedingly charming.

Andrea, Ted and I sat on the low, well-worn wooden stools in front of a beat up wooden table covered with around forty open bottles. Masson brought out some Tomme de Savoie, a local rustic semi-hard cow’s milk cheese, a few links of dried saucisson, and some great bread—none of which Ted would touch until after tasting the wines. (I was starving and dying to dig in, but I followed Ted’s lead of tasting on an empty stomach, being careful to mostly spit). Jean-Claude gave us glasses and started to pour.

Somewhere along the way, Jeane-Claude decided to name a couple of his wines after his children and Ted’s favorite just happens to be the one named after his daughter, Lisa. Ted raved about the wine’s “power and mineral exuberance. It’s ethereal, while at the same time strong and incredibly energetic, charged and electric.” (There was that word again). He said, “it dances on its tiptoes and is just obviously a stunner.” I was hoping Andrea was okay with the fact that Ted had a crush on that bottle.

The Cuvée Traditionnelle, on the other hand, is from older vines and has “a deeper and denser taste, more typical of the old-school Savoie style. It’s baroque, antique, heavier, with the bright flesh and heavy setting of a girl in a Ruben.”

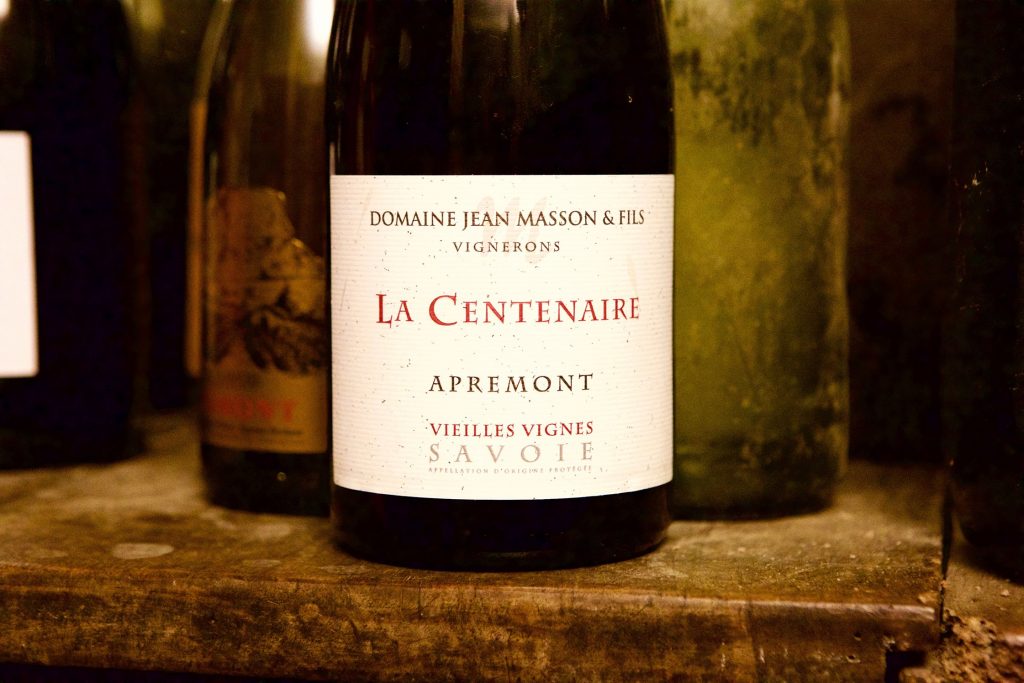

Masson then poured a wine labeled as Collection, which Ted puts second on his favorite list here. “It’s more toned and serious than Lisa, but not as honed as the next wine in the range, La Centenaire. Yet in its high notes and low notes there is an intense friendliness.”

Next in his rankings was La Centenaire, which comes from old vines as well (100 years), but it’s “more mineral and pure than the Traditionelle. It’s like the Lisa, but even more finely tuned, a beam of light. It’s denser, more refined, with precise mineral nuances and a compact core.”

As we tasted, Ted remarked that his customers crave knowledge about what they buy, and a great way to learn is by tasting multiple wines from each producer. If he brings in only two cuvées, that’s not enough to demonstrate la gamme, or, the range of a collection. He believes that with Masson, a minimum of four different wines is needed to do this, even though he wishes it made sense to bring in his entire range. This kind of variety “illustrates the seriousness of the maker, their ability to demonstrate a broad skill set in their craft.”

I should note here again that I’m not a wine writer, nor am I an expert in wine. Though I do have a good deal of experience, I consider true experts to be in another league, and again, the idea was that I was there as an outsider. I’m not nearly to the point where I can describe wine’s nuances in such abstract and poetic terms as can the likes of Ted, or his friend, food and wine writer Jordan Mackay. They know these wines well enough to speak of them as if they are describing people—old friends, even.

Some who don’t possess this ability can dismiss it as pretentious. To make fun of these experts is a joke in pop culture. But when you know them personally and understand that they are truly sincere, you can see it as genuine enthusiasm and inspiration. The average enthusiast tends to remark merely on flavor and nose characteristics, which can be also be dismissed by non-enthusiasts as pretentious; it’s a lower descriptive tier yet still part of a language that can leave the uninitiated cold.

Being able to tap into the more abstract characteristics of a wine takes the experience to an entirely different level of enjoyment, intellectual, emotional and sensory engagement. I’ve been able to take a taste and give it some thought for a while and come up with observations that are probably a bit thin, but guys like Ted instantly go to these distant places, straight to impressions, emotions, and even memories of childhood smells that the sensory characteristics evoke. I said at one point that one of the wines reminded me a little of the smell of aspen trees in Colorado, where I grew up, and was relieved when Masson validated (or humored) my comment with a smile and nod. Ted said that anyone can pick up on these notes, if only they are open to them.

Frankly, I’m a little in awe of this skill. It’s like any other time when you don’t speak the language, when they’re translating and you just have to take their word for it. The upshot is that anyone who wants to get to this level just needs to drink a lot of wine and practice opening up to another realm of the experience—your mission, should you choose to accept it.

After we finished sampling Masson’s range of six, he said he had something else for us and disappeared with a wink. When he returned he was holding a magnum with an unusual looking label and the words, “Mes Kouilles” imprinted on it. He said that this was his “personal wine,” his labor of love, a product that reflects his efforts in every way. It just so happens that the name is a deliberate misspelling of Couilles, which means balls. Yes, you’re reading that correctly: the wine’s name is a play on “My Balls.”

Even more disturbing (I mean, provocative) is the material of the label, which has the wrinkled texture and soft feel of scrotal skin. Ted mused that all this must have come about after Masson partaking in a bit of cannabis, which he definitely doesn’t eschew. Masson had a good laugh as he filled our glasses halfway and told us that a couple of Michelin two stars in Paris carry “his balls.” It’s a good wine, and I couldn’t help but think that some sommeliers were also having a bit of a subversive laugh with the lark.

When the tasting was over, it was time to sit back and just drink, eat and relax a little. His assistant came in with a two-foot long ham leg in his fist, Fred Flintstone style, and began hacking off thick slices. He had cured it himself and it was like very salty prosciutto that went perfectly with the local cheese and Masson’s balls. He was an interesting and friendly guy who was staging (basically interning) with Masson while he also held a position as sommelier at a local Michelin one star restaurant.

As Masson gnawed on some meat and took a big drink himself, he talked a little more about the natural wine movement, how, like in his fields, he generally does as little as possible to interfere in his cellar. He said the old-guard vignerons in France say that natural wines all taste the same because by limiting manipulation, they’re all essentially made the same way, while the vin naturel makers say the old style wines all taste the same because those vignerons kill all the microbial life. So the battle continues, and Masson plays Switzerland by doing a little bit of both.

We wrapped up and said our goodbyes with the usual promises from Ted that we would come again as Masson said we’re always welcome. As we pulled away, Ted mused on the purity of Masson’s approach: “The grapevine interacts with the soil and channels specific characteristics into the grape, and you have a choice to manage this process— to either stand with nature, or against it.

“Every time you work against nature, there are consequences for every benefit. The vigneron is one of the last bastions of this choice, aside from other organic farming, which is still a tiny minority in world food production. Doesn’t it make sense to cultivate what nature has to give instead of manipulating it?”

Next: Nature Worshipper