Pedro held out a slab of granite that had decomposed almost completely into some kind of dense mudstone. Each mineral crystal was in place as if it were still solid rock. It was amazing; the soil was completely eroded in place. The rock bent a little before breaking with very little effort. It was a fragile soil that was completely available for the vine to plunge its roots as deep as they could go. When the vines dig this deep, Pedro calls it the vine’s “200-million-year-old Michelin three star tasting menu.”

“Everyone talks about their soils and how their vine roots plunge deeply into them. How can you really know what your roots are doing if you don’t dig holes to observe them directly? Really… how do you know?” he exclaimed. “People have it wrong,” he continued. “They say meager topsoils will be too nutrient deficient. But there is a feast here,” pointing to the fissures, “that awaits the roots deep in the soils.”

We jumped into the car and headed back to have dinner with his family in the coastal village, Pingueral, a town with an entirely rebuilt center, after a tsunami destroyed it in 2010. Pedro said it would take forty-five minutes to get back, but it took an hour and a half. Time got away from us because I threw a flurry of questions Pedro’s way, and he seemed to prioritize answering them over making good time to his family’s house. Unlike the hungry people following us, I didn’t mind.

Pedro explained a theory on the vine’s relationship with soil that has gained momentum in the last decade or so. The idea (largely promoted by the well-known French soil scientist, Claude Bourgignon) is that the life and magic happens in the top soils and not deep in the bedrock; perhaps meager topsoils in granitic vineyards, like those in the Itata (similar to France’s famous granite soils of Cornas and St. Joseph) weren’t sufficient for the vine to get all it needed to thrive and develop a deeper range of complexity. Although Pedro acknowledges the logic of this theory, he doesn’t completely subscribe to it.

As we drove toward the coast, I asked Pedro more about subsoil fractures and their relationship with vine nutrition. I threw in a concept I’ve heard many biodynamic producers talk about: the need to build up microbial activity in topsoils as a major key to unlock a wine’s terroir. The concept of “building up soils” was always a little strange to me; it seemed the opposite of a terroir wine. Before it was a vineyard, if the land never had particular microbes and all of the sudden these new alien microbes were introduced, wouldn’t that be changing a vineyard’s natural terroir even further?

If a topsoil is rich in everything the vine needs, it’s like the vine is eating fast food

“If a topsoil is rich in everything the vine needs, it’s like the vine is eating fast food,” Pedro quickly stated. “For example, in clay top soils they have a “full meal deal”: easy to get, quick to give, but no [real contribution to the wine’s] taste.”

“Granite topsoil [unlike clay] is a low calorie meal, like a lean but nutritious dinner with only something like chicken and lettuce. But the vine can plunge deep into the granite’s vertical fractures,” he continued, “and while the topsoil’s portion of chicken and lettuce isn’t enough to sustain the vine’s nutritional needs, each foot below the surface gives another serving of chicken and lettuce, and further down more and more portions of chicken and lettuce,” he said, looking at me over the top rim of his glasses. He pushed them up his nose and continued, “this is enough to keep the vine fed, but only on lean and clean food. I want my vines to dine on a healthy multi-course Michelin-starred tasting menu, not fast food.”

Pedro’s chicken and lettuce analogy was funny, and it made sense to me.

At Pedro’s family’s house we were greeted by his two kids, his wife, Camila, and her mother and stepfather. There was also an innocent and quiet-looking, overgrown short-haired puppy that, when given the chance, mauled you with an endless flurry of jumping, biting and bullying, leaving you with slobber and needle-sharp hair all over your hands and clothes.

The family was ready for us with typical Chilean appetizers like shrimp cocktail, crab claws, and abalone baked in cheese. We were handed glasses of sparkling wine from a project of Pedro’s, which was wonderful surprise. Then we tasted through a few white wines from another one Pedro’s Chilean wine projects, Clos des Fou. After a fantastic salmon dinner with a series of international wines, including a magnum of Saumur blanc (Arnaud Lambert’s 2014 Clos de la Rue, which I brought), a Barolo from a lesser-known, but great producer, Marco Marengo, and many more international wines one wouldn’t expect to find in this remote part of Chile, we were ready to hit the sack.

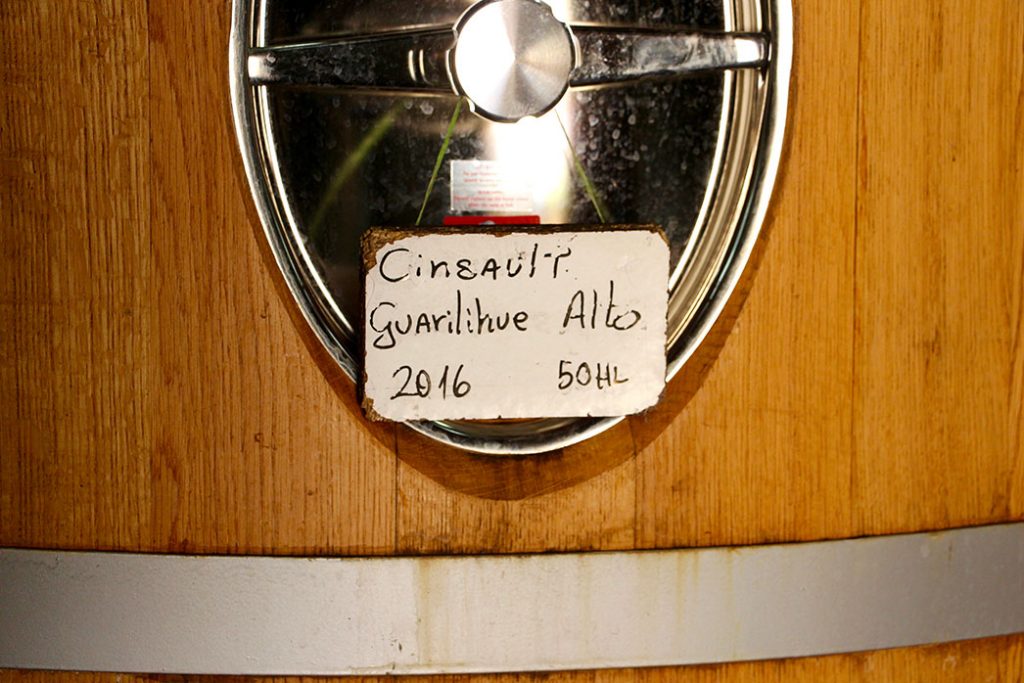

Early the next day we were off to Cauquenes, the location of Pedro’s winery. After a two-hour drive, we entered an old, run down, but charming hacienda-style government building that he was able to use as their winery. Pedro brought us into his vat room full of concrete, stainless steel and large oak tanks, to taste through his single-vineyard Cinsault and Carignan wines.

Once you visit a wine’s vineyards and see the soil and rocks it comes from you begin to really understand what you are tasting. After seeing Pedro’s pits and the ancient, newly unearthed stones, they become burned into your memory, giving a perspective on the wine you can’t have unless you’ve been there.

The first Cinsault was elegant, like a beautiful Beaujolais.

I was pleasantly surprised by how different each Cinsault was. They all went through the same winemaking process, with very little intervention or styling. Each wine had a clear voice, unique to each vineyard. The first Cinsault was elegant, like a beautiful Beaujolais; the second’s exotic and richly perfumed character evoked a strong emotional response; the third was gritty and structured with loads of peppery spice, like it was mostly made of Syrah; and the fourth was dense, with high-toned aromas of damp, green forest floor with wild, tiny black and red berries.

I was taken by the unexpected, intensely mineral nose of each Cinsault grown on various granite soils with different physical structures. I later proposed to buy and import them to California as separate cuvées instead of all blended into one, which Pedro currently does. In the palate, all were earthy, mineral and textured with flavors I usually associate with Old World style wines. Embodying the intense, honest, pure and humble spirit of Pedro, I felt like I finally had my first uniquely Chilean wines.

At some point in my wine career I wasn’t sure that I would find New World wines with this level of x-factor (metal, mineral and texture), while maintaining the character of a noble wine commonly found in the Old World. I’ve had my fair share of New World wines and so few are as raw and authentic as these. Unfortunately, many New World wines from interesting terroirs are tinkered with so heavily they often need to be psychoanalyzed to find their terroir imprint.

After the Cinsaults, we tasted Pedro’s two Carignans. They seemed to subtly express the scent of pine and eucalyptus that we had smelled at the vineyards the day before, something we didn’t pick up in the Cinsaults. But from this, a dynamic set of richly scented, earthy and spicy reds emerged. It seemed obvious where the forest notes came from, and I asked him to weigh in on that perception. He agreed that it was likely from the trees. The topic of a vineyard’s surroundings and its effect on a wine’s aroma and flavor is another (true) story, but that’s for different article…

After a quick sandwich in the laboratory and a tasting of Pedro’s newly bottled wines, we were on the road again to our final spot, Guarilihue. We had only three more hours with Pedro, but they would prove to be some of the most interesting hours of our trip.

Part 5 of 6, “Los Reconquistadores” will post next week.

To keep up with this story you can sign up to our email list, or check in next week at the same time and you will find part 5.