Welcome to the April edition of the club! This month we have wines and a theme that are not only near and dear to our heart, the wines and theme are near and dear to each other. That is, the wines are Chablis, and the theme is rocks. If there’s a wine that appears to more transparently regard its soils than Chablis, we have yet to find it.

If there’s a wine that appears to more transparently regard its soils than Chablis, we have yet to find it.

It’s always interesting to compare Chablis from different vineyards, so this month we’re keeping our focus tight by examining two distinct Premier Cru vineyards, while keeping the vintage and producer the same. Specifically, the two vineyards highlight a different texture in rock—one is harder, the other softer. But first, a word on Chablis…

Forgive the editorializing, but if you’re not drinking a ton of Chablis these days, you’re missing out. It’s Chardonnay. It’s Burgundy. It’s dry, racy and piercing, but with some lemony flesh to give it substance. It’s still way undervalued. And it’s always delicious and appropriate, whether as an aperitif or with so much of what we eat, especially now as we move into spring and summer vegetables.

And it’s always delicious and appropriate, whether as an aperitif or with so much of what we eat, especially now as we move into spring and summer vegetables.

So what do we know about Chablis? While technically a part of Burgundy (the northernmost part), it’s actually closer by distance to Champagne than to the Côte d’Or. It’s a tight little region, with the village after which it was named at its center. The little river Serein ambles by, dividing the vineyard land into what are conventionally termed them Right Bank and the Left Bank. The subsoils here are limestone, Jurassic limestone, topped with layers of marl from the Kimmeridgian and Portlandian eras. The interaction between the three strata appears to be key. A lack of unbound clay to mediate between the vines and the rock, likely contributes to the ‘bony’ profile of Chablis, especially vis-a-vis the comparatively rotund white burgs of Meursault, Puligny, and Chassagne. Chablis’ climate is also colder and harsher than the Côte d’Or’s, which again strips flesh off the resulting wines.

The subsoils here are limestone, Jurassic limestone, topped with layers of marl from the Kimmeridgian and Portlandian eras.

Conveniently, all seven of the great Grand Cru vineyards are huddled collectively on one massive slope, located directly across the Serein (and in full view) from the village of Chablis. The Premier Crus, forty in number, are another story altogether, as they lie scattered on slopes around the hill of Grand Crus, as well as across the Serein on the Left Bank. Most of the forty PCs are not famous enough to have their names used on labels, but there is an all-star team that basks in the limelight—indeed, more so than some of the more obscure Grand Crus. We’re going to look at two of these this month. So, on to the wines.

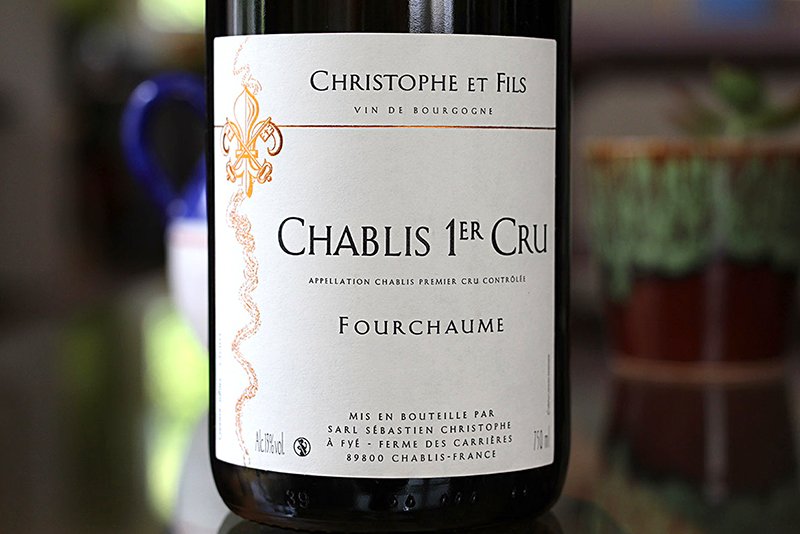

2015 Christophe et Fils 1er Cru Fourchaume

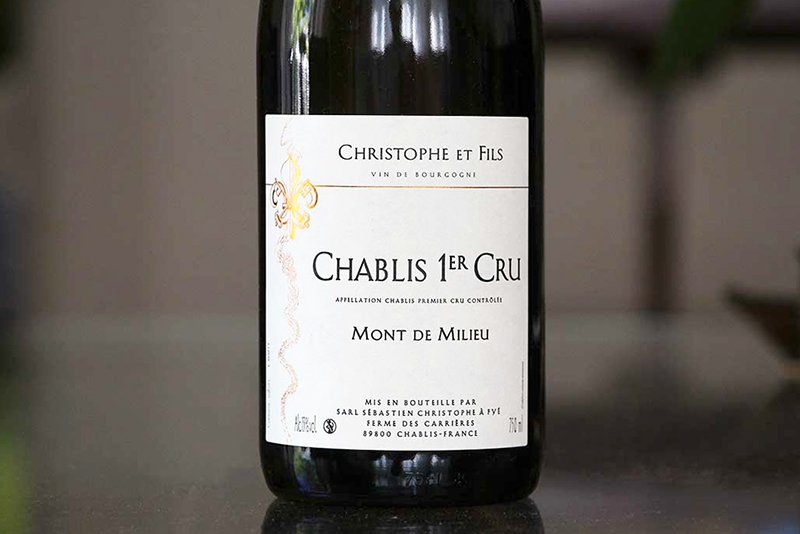

2015 Christophe et Fils 1er Cru Mont de Milieu

So the producer is our budding superstar Sebastien Christophe. We love his wines, but we also love him, the ultimate underdog. While known for its stolid rigidity, France’s wine culture still allows for a lot of mobility. That’s how a young kid gifted just a couple of acres of average vineyard land in Chablis could rise up seemingly out of nowhere to make brilliant wine from the three most heralded Premier Crus in the region. That happened because he was also gifted with a good bit of moxie and a cranking worth ethic, which will you get far anywhere.

What makes Sebastien’s wines so great? Well, as is the case in Chablis, it’s not the winemaking, which is pretty standard for the region, as the goal here is never to showcase cellar prowess, but rather the nature of the vineyard. Sebastien vinifies and ages wine overwhelmingly in stainless steel, as is the general practice of the region. Less than 10% of the wines see elevage in neutral oak barrels, providing a little textural and structural contrast to the bristly energy of stainless steel.

On to the vintage, 2015, which was a warm one in Chablis and full of sun.

On to the vintage, 2015, which was a warm one in Chablis and full of sun. Even though it’s a cold region, Chablis still can have problems in hot years. While most critics have dubbed ’15 a very good year, the heat can show itself in wines that are be Chablis-like in flavor, but lack in the nerve and drive that we crave. We’ve tasted some of these in the region, though Christophe’s wines have evaded the issue. (However, you can taste how an excess of heat and sun benefited the lower-class vineyards simply by tasting Christophe’s unbelievably delicious 2015 Petit Chablis.)

So, the tasting. It’s always nice to open the two bottles for a direct comparison. However, there’s no pressure to do so, as long as you take good notes to compare them in your mind!

You’ll find the flavors in the two wines fairly comparable. The great differences are in the structure and the texture, which are truly the hallmarks of Chablis in general. And these differences are immense. The Fourchaume is steely and powerful, with intense acidity razoring through it, honing its edge on the side of a Meyer lemon. The Mont de Milieu is almost the opposite, carrying its minerality gently, like stones in a cloth pouch. It’s a more subtle wine, softer and milder, but with greater complexity, varying its citrus notes with hints of dry earth, stone and meadow flowers.

Let’s look at the vineyards, both of which are likely universally considered among the top 5 Premier Crus in Chablis. Fourchaume resides just north of the Grand Crus, of which some people consider it a continuation. A funnel-shaped valley (which grows only Chablis village and Petit Chablis) separates the two areas. Fourchaume curves around a long hip of a hill, providing a number of exposures from southeast to southwest. The major difference between Fourchaume and the Grand Crus is the shape of the hillside. The latter curves inward, forming a heat-gathering amphitheater, while Fourchaume juts outward, more exposed to the winds and cool air of the Serein valley.

In contrast, Mont de Milieu, lies south of the Grand Crus, also on the Right Bank of the Serein. It climbs a hillside at an almost direct southerly exposure, meaning that its orientation to the sun in summer is direct and brazen. It’s one of the warmest of the Premier Crus.

The soils in each vineyard are textbook Chablis, but there is a difference. Last time he was in both vineyards, Ted Vance (The Source’s founder) noted that the stone in Fourchaume is a harder variety, more fragmented, brittle, and craggy. Mont de Milieu, on the other hand, boasts softer soils and is famously less stony than some of the other crus.

Why would harder soils produce a harder, more linear and “strict” wine, while softer rocks make for a softer, more contoured one? Who knows? It’s one of wines great mysteries that metaphors used to describe the soils often apply in the same way to the wines. Scientists would scoff at this, but the lab technicians with the most information are the winemakers who taste these wines all the time, year after year. And they back up such claims. It’s also possible that the differences between the wines were heightened in a year like 2015. Given the excess of sun and heat, a warm site like Mont de Milieu may truly end up with less acidity than Fourchaume, which is more exposed to wind.

It’s an interesting comparison. But, as always, the reward for thinking so deeply about the wines is getting to drink down the whole bottle. We hope you enjoy these 2015 Chablis as much as we do.

All best,

The Source