"Beaujolais is not what it used to be…" I bet you’ve never heard that one before.

Recently I had a conversation about how bright red, crunchy fruit renditions of Beaujolais contrast those with more ripe fruit components and deeper textures, with consequently higher alcohol. I found myself defending the latter, not because it’s what I prefer (quite the contrary), but 2005, 2009, 2011 and to a lesser degree, 2003, all fit this profile, as do some of the more recent, like 2015 and 2017, as well as (it seems) the incoming 2018. Some recent vintages more calibrated to my preference, like 2013, 2014 and 2016 would likely not have been considered top years in the recent past, except to people like me who prefer the general style of those years, but I’d like to stand by the other expressions of this appellation as being just as authentic.

One of the points we debated was that while there is still elegant, cleanly made, bright red-fruited Beaujolais out there in the market, why are some of the recent vintages by some of the “greats” (who prior to the last string of vintages, starting in 2015 seems to be known for their more-restrained style) now regularly demonstrating higher alcohol, more power, and a stretch into overripe fruit. One of those producers criticized for bigger alcohol and riper fruit was one we import and is strongly associated with our company.

What was most interesting about the observation and commentary from my friends, who are total wine nuts, was a complete contrast to another friend, a Master Sommelier who’s been around a while and didn’t care for this producer’s wines when we first began to import them. He found them too green and underripe—comments directed toward the producer’s ‘13s and ‘14s, banner vintages for my style of Beaujolais. I was as perplexed by the green and underripe comment back then as I am now about the overripe and high alcohol from the same producer within a span of four or five vintages. I find this degree of disparity of opinion about the same producer unusual, to say the least.

Most of us inside the wine business have met those incredibly brilliant sommeliers and wine pros with outrageous talent and encyclopedic memories. They can rattle off facts and details about wines you may not know but feel like you should. Everything under the sun in the last four or five years seems to have been tasted and judged, but to drink an entire bottle alone without being accompanied by fewer than five other wines, or five other people around is becoming less common within the trade.

While I enjoy the good fun of a taste off, this approach to wine analysis is a bit of a contrast to my usual practice as a wine importer. Importers have a unique view into a wine’s life and how they twist and turn, revealing surprises (not always good ones) over many hours, with numerous examples being observed from their earliest years in barrel, as well as in bottle throughout their development. We may not taste everything under the sun, but we’re able to observe the same wine as it changes from one moment to the next, for as many as ten hours in a day. Then, tasting different bottles of the same wine over the course of a few days shows that no bottle is exactly the same. What’s missing in the analysis of Beaujolais among the talented new wine pros is the same for all of us when new to something. Context.

2015, ‘17 and ‘18 in general show more concentration than the previous series of vintages that seemingly spearheaded the boost in Beaujolais’ popularity. Starting in the late 2000s and early 2010s, it reached a feverish pitch by the time the ‘14s hit—in no small part due to the second SOMM film, which gave Beaujolais a big shove in the direction of wine pop culture. Droves of new fans flocked to slurp down Beaujolais filled with unpretentious joy and freshness from those years.

Back then the most celebrated Beaujolais wines from any domaine were largely from vineyards with old to ancient vines. In less hot years they show depth and complexity, along with the crunch in some of the exuberant, high-toned vintages. In the more recent ripe years they show equal complexity and depth, but are calibrated for a different palate than those who prefer the crunchy fruit and freshness from a cooler year, like I do.

Within three of the last four vintages (again, excluding ‘16) things seem to have changed without any reversal in sight back toward the way it used to be—that is, for many, only five to eight years ago, when some of the vintages (like 2010, ‘12, ‘13 and ‘14) demonstrated characteristics more closely related to their Burgundian neighbors to the north. ‘15 and ‘17, and likely now the warm ‘18, could be in some cases equally associated to wine from the Northern Rhône Valley in taste and texture; and it stands to reason, when you consider the similarity of the soils (granite and schist) that make up a significant proportion of the Beaujolais Cru areas and Côte Rôtie, all the way down the right bank (west side) of the Rhône River to Cornas.

Right now, those with far more than a couple of decades of experience with Beaujolais might want to poke me in the eye for defending riper-styled Beaujolais as part of its history, and as I wrote this piece I felt like I might deserve it, because part of me agrees with them. However, if you’ve read the fantastic account of Kermit Lynch’s time with Jules Chauvet in his book, Adventures on the Wine Trail. Chauvet commented about the “little vintages” of Beaujolais having 9 to 10% alcohol, but stated that even in 1945 and 1947 they were “unusually rich in natural alcohol” and after that they were “always 13 to 14 degrees.” There’s also talk about overcropping and full-tilt manipulation of the grape musts to bring the alcohol levels up as much as 4.5% from its natural level.

Lynch’s account is awesome. I sure wish compelling and balanced Beaujolais that hit a natural 12% or less in alcohol was more common, but sadly, I believe this may be increasingly more rare in the future. For the vines in the cru areas of Beaujolais, there’s no going back with this climate change breaking heat records almost every year. And sure, you can pitch in the standard rebuttal that growers can “just pick earlier,” but grape vines don’t work like that if the balance of sugar, acidity and taste is a consideration. Yes, it does work if all that is important is the glou glou (glug glug, in French) made with carbonic fermentations and knocked back as a wine shot (vying for top prize of bad wine trends ever, in my opinion), but it isn’t for serious winegrowers with deeper aspirations for their wines.

Don’t get me wrong, I love my glou glou, but glou can be serious too, baby! It has to start with serious grapes just like any other wine with big potential. Ever heard a winegrower say they pick based on taste? I assume you have, and you can be sure they aren’t referring to the grape sweetness alone (because a refractometer is much more accurate than a tongue), but rather the balance of the components—texture, tannin, acidity, phenolic ripeness, sweetness of the fruit, and most importantly how it tastes and feels tous ensemble.

Contrary to today’s market trend, what were considered the most successful years in Beaujolais were its most ripe, which were also considered the most age-worthy. Today, there is some semblance of backlash from less-experienced buyers against two of the most recent vintages, ‘15 and ‘17, and I expect there will be more of the same with the warm ‘18s. Newer Beaujo fans likely expected the continuation of elegant vintages and heaps of the glou, but that’s only a part of Beaujolais’ story.

Many long-standing growers and wine writers in Beaujolais claimed 2015 a great vintage. In fact, one of the region’s luminaries, Jean-Louis Dutraive (pictured above, in 2014, before he exploded onto the scene), told me that it could be the greatest vintage of his lifetime because of the body, power, vibrancy of the fruit and unusual balance of naturally high acidity. The wine critic, Josh Raynolds, from Vinous, described it as “superb if not atypically ripe,” and one of my favorite wine writers, Andrew Jefford, from Decanter, described the vintage as “great.” Indeed there was more praise from critics and growers, but not so much from those who recently walked in the door—an understandable reaction coming off of the previous couple of years.

It may be an overlooked fact that Beaujolais is a warm to semi-hot wine region and is much more so than its surrounding neighbors, like Burgundy, the Jura, Northern Rhône and the Savoie. Don’t forget, Chauvet said that back in 1945 and 1947 they hit big alcohol levels for the time (again, 13-14%), and this was likely with hugely cropped vines and canopies that looked more Rastafarian dreadlocks than today’s “High Bald Fade + Thick Side Swept Hair + Shape Up + Undercut”—yes, that’s a real contemporary hairstyle that could stand in for the highly groomed modern vineyard… If they had been cropped less and manicured more in line with a metrosexual cut, the alcohols would’ve been even higher. To put it bluntly, to get the same kind of crunchy fruit characteristics year after year is not in Beaujolais’ cards, and probably hasn’t been in most of our lifetimes.

Much of Beaujolais’ vineyards are quite exposed to an all day supply of sun during the latter part of the vegetative cycle and through the fruit cycle, all the way up to harvest. It doesn’t help that most of the suitable vineyard areas have been deforested and planted to vine, and the vast majority of them have been sprayed with herbicide. Trees and undergrowth help at least a little to mitigate some heat in the face of the sweltering sun.

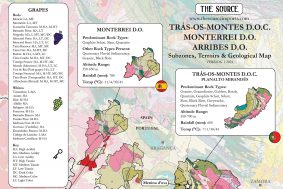

Another significant challenge for Beaujolais weathering the heat storm is its most prevalent soil types, granite, schist and alluvium, which are well drained but this further exacerbates the potential for intense hydric stress during heat spikes, unrelenting summer heat and droughts.

As a consequence of the increased heat, the old vine parcels that most of the top producers have in their stable typically reserved for their best wines seem to be exacerbating the problem of too much power and concentration in hotter years, since old vines give these things a boost to begin with. Perhaps Beaujolais’ wealth of ancient vines may be somewhat of a liability when in pursuit of lower alcohol and less ripe tasting wines. Okay, now I’m ready for another sock in the eye from all comers…

Old vines produce small crops with concentrated grapes, which means concentrated sugar, acid, flavor, extract and potentially increased aromatic and flavor intensity. They often ripen earlier than younger vines (which normally carry a larger crop often requiring more days on the vine) and in warmer years consequently render even greater density and less high-toned crunchy fruit than what vintages like ‘13 and ‘14 brought. In these two vintages the top growers knocked it out of the park with seemingly everything, especially their old vine parcels; the same bottlings that in ‘15 were monstrosities by comparison to the fresh, more upright versions in the previous two years.

How long will it be before privileged sun exposure and effortless ability to reach ripeness each year become liabilities? When it’s hot, the vieilles vignes sites crank out big boys that the market has now begun to largely shun, while in a cooler year, they are unmatched in depth, balance and flavor and the market can’t get enough. In Beaujolais this unfortunate trend already appears to be well underway and sadly there seems to be a shortage of insight which has led to a lack of empathy by many buyers. Each grower in Beaujolais is facing climatic circumstances that have not been seen in recorded history.

Even the greatest of the great producers of Beaujolais struggle to manage high alcohol, ripeness and the likely cellar problems that come with vintages like ‘15, ‘17 and perhaps ‘18—stuck or slow ferments, elevated volatile acidity and such. All these factors can leave wines exposed on many fronts, especially those that walk the razor’s edge with low to no SO2 to satisfy the natural wine purists. The elevated magic many of us love about less ripe years is likely less than half of what may be more common moving forward as the years get hotter.

Then there’s the hail… and the frost… It takes at least a year for vineyards to get back to form after these increasingly more intense and frequent catastrophes. With back-to-back hail storms in ‘16 and ‘17 and frosts in places like Fleurie and Morgon (and other regions), it’s been a solid uphill battle over the last few years to find that crunch and elegance in some parts of Beaujolais.

The after effects of hail and frost the following year may concentrate the fruit a bit more due to small yields during the vine’s recovery process. Then the rest of the dominoes fall. In 2017, while it was already a very warm vintage, the hail and frost of ‘16 imposed lower yields, and the spring frost and summer hailstorm in ‘17 doubled the recovery time needed for the vines where they were hit back to back. Where does that leave the ‘18s? I don’t know because I’m writing this article before I’ve had a chance to taste a finished example with a couple of months in bottle to see what’s really happened. It’s tough to know where it will go but what I tasted out of barrel and tank seems promising, without entirely falling into the elegant camp.

So where does this leave Beaujolais and its followers, both new and historic? Is part of the answer to this conundrum that if you want more slurpable Beaujo glou glou, perhaps the stronger probabilities lie within wines made from young vines that naturally produce lower alcohol as a result of the higher yields? Or should the focus be on good producers who have no problem setting the course for higher yields which bring the desired lightness and immediacy that some of us enjoy?

On the former side of the taste spectrum is the forty and over crowd, the ones who spend the most money in restaurants and on wine cellars and who likely don’t have the same calibration as those who walked into wine when the pendulum was in full swing against alcohols above 13.5%. I don’t think that specific demographic has a problem drinking wines loaded with the kinds of big flavors and matching alcohols that the more ripe vintages yield.

While I admit it’s not always my cup of tea for wines with higher alcohol and richness, I believe I am in the minority demographic for my age bracket (over forty) who prefer elegance over power and has a healthy budget set aside for a good amount of drinking. The hard pill to swallow as an observer and wine merchant is that it seems like Beaujolais is already in a climate pickle, yet there’s a push for lower alcohol wines that are not going to be a regular part of its future.

Perhaps the producers might begin to consider a retreat further back into the Massif Central where there is an abundance of similar soil types, but with less intense summer heat and exposure, and dense with forests for improved temperature balance between day and night—the key to balance in wine grown in warm climates. That said, I’ve never heard talk of that option and I don’t think the local vignerons are in agreement regarding the low alcohol stance on their wines taken by some in the market. Many love power in their wines as much as they love elegance.

I also pondered the idea that the lower-classified zones of Beaujolais and Beaujolais Village, further south and largely perched on limestone and clay soils, are better equipped to weather the heat than the meager soils that dominate the Beaujolais Cru landscape. But while these areas may have the same sun exposure, their heavier soils may render a heavier style Beaujolais than those grown on finer soils that impart lift, freshness, texture and mineral feel to the abundantly fruity Gamay. An example of how powerful limestone and clay can be with Gamay, try a comparative tasting of Jean-Louis Dutraive’s Brouilly wine grown solely on limestone and clay soil with one of his Fleurie wines on granite. Those with a moderately experienced palate will see a profound difference in their shape and impact.

To have the same wine delivered year after year in Beaujolais despite the growing season is unrealistic, now more than ever. It’s also contrary to the very ideal of a more natural wine with minimal intervention in the cellar. Indeed, a domaine can output wines with the same alcohol and acid level every year, but not without unnatural adjustments to the fruit in the cellar.

Winegrowers are in pursuit of balance, and some years in Beaujolais it’s when the grapes are at a potential alcohol of 11%, with the right acid profile to match, and with others it can creep over 15% and still be wrought with acidity, as it was in 2015. Gamay grown in this part of the world consistently demonstrates dramatic swings of balanced ripeness from one vintage to the next, each with their own merit. Beaujolais seems to be especially feeling the impact of climate change as of late and has made a valiant effort of rolling with nature’s heaviest punches. We would all do well to view the unique versatility of Beaujolais as its winegrowers do, and embrace its ever-changing face.