(Download complete pdf here)

Photo courtesy of Katharina Wechsler, harvest 2024!

As I begin to write this in the middle of September, the leaves of Catalonia’s Costa Brava have started to show the first signs of color change. The sun’s angle is noticeably lower and the sky has a hazy cast softened by feathery cirrus and stratus clouds. The temperature? Perfecto. It’s easy to miss the fall when the summer is ablaze, but the first day of real fall weather I find myself lamenting the passing of those first days of summer. I’d like it to always be like May in the arc of my life, but at forty-eight, perhaps I know I’m getting closer to my own fall season, even if I know I’d also be lucky to get past the first week of July on my route to the other side.

Everything seemed relatively fine when I returned to Spain at the start of the second week of September after two months of bouncing around the States. But at this moment, Lower Austria is flooding and the Langhe is being held hostage by ambivalent weather patterns between constant downpours and rays of hope that barely pierce the clouds. Our neck of the woods in Portugal is on fire, literally and figuratively, and we’ve had to check in with our neighbors there to see if our house hasn’t been razed to the ground. It’s fine, but others a few ridges over were not so lucky. Everyone in every part of Europe is stressed about harvest and how things will end up with the fruit that’s still on the vine. I’m often praised for “bringing California weather with me” to Europe and I guess this association has remained consistent, considering the all-too-regular recent flooding and burning in the Golden State. My “contribution” on this front might not be as appreciated lately as it once was!

My visits with many buyers in other states outside of California were filled with cautious optimism since the changing of the guard within the Democratic party. Aside from many political issues in which we respect different perspectives, those of us in the import industry can’t accept implicit indifference to the potential reelection of former President Trump, who wants to blanket all imports with as much as a 20% tax, and even airing the casual threat of an even higher one. This would be devastating, even for those not in import trades. In criticism of such tariffs, the media often says the American consumer will pay the difference, not the country producing the goods. But that’s not my experience. Remember those wine tariffs that started in October 2019? Companies like ours that import goods had to pay at least half of the tariff because the market would never take on an overnight hike of 25%. So we bought whatever we could, and European growers just sold what we couldn’t acquire to other countries, so many people here lost a good portion of their allocation of special wines. The tariffs and then the pandemic slowdown combined to foment mistrust in the US’s stability, resulting in a redistribution of interests away from the US market.

With the global downturn as of late, a 20% tariff would be a more devastating event for our European growers because the world is facing a different circumstance than in 2019, 2020 and 2021. Many would have no choice but to lower prices because the rest of the world’s wine market is generally static, or even declining faster than in the US. This will be difficult for them because of the massive inflation that has yet to slow, while their costs remain elevated. Some approached this as a pass-through cost and folded it into the end product without adding higher margins to compensate for the inflated costs of support goods such as labels, corks, bottles, etc, which would hit any business hard.

Every European grower is now looking at the US–and directly at us–to help solve their stock problems. But, we won’t be coming to anyone’s aid if new tariffs are imposed in January. Suffice it to say, anyone in the import business that doesn’t vote blue this season is casting a vote against their own financial security.

After the new arrivals list, be sure to check in on the 2024 Vintage Report further below. It’s a quick summary of the 2024 season from Austria all the way to Portugal, supplied directly from our growers.

This month we have a decent dose of arrivals, but I won’t dwell so long on growers who’ve been with us for a while because we’ll need extra time for two new ones. Each has been on the table for a while now but the unexpected economic downturn that started with the film industry strikes in California last year stayed our hand for some time. But we couldn’t wait any longer, and neither could our sources! After shedding more than five import suppliers over the last five or six years and many domestic producers, we’ve wanted to fill the gaps with important things we know sell well.

As mentioned in our August 2024 Newsletter, the most thrilling visit on my French summer tour was with the Richoux family, one of my spiritual and quasi-familial wine destinations in Europe. While the heat is changing the landscape from year to year, the magic of Irancy and Richoux is still there–perhaps it’s even greater. Thierry’s sons, Gavin and Félix, have had a lot of influence over the last ten years; their biggest change was organic certification (though they were already working organically) and with biodynamic practices, no added sulfites until just before bottling, and smaller format barrels (in this case, 500-600L instead of only one year in the large 55-80hl foudres and another one in steel tanks) among other small adjustments. The wines are intended to take on more openness and lush fruit–a contrast to Thierry’s style, which often feels like classic cool climate Italian-style wines made in Burgundy. What’s arriving this month is the 2019 Irancy, a spectacular wine that finds the balance of ripeness and freshness. This year, it’s a little Vosne-Romanée-like with its delicious, full red fruits and well-rounded balance of body, structure, and matière. If one were to blend the brightness of 2017 and the density of 2015, they might arrive at this 2019 Irancy. Also off the boat is their outstanding Crémant de Bourgogne from Pinot Noir grown on the south side of the horseshoe-shaped amphitheater of Irancy, facing north.

In Italy, we have new arrivals from two generous and humble families in Piemonte, Fabio Zambolin, from his Coste della Sesia vineyards inside the Lessona appellation, and La Casaccia, in the small village, Cella Monte, inside the Monferrato Casalese.

With Margherita Rava’s visit to California, everyone who had the pleasure to meet her couldn’t resist her charm and the charm of her family’s La Casaccia wines. They are as authentic and carefully farmed and crafted in their cellar in all of Monferrato, and represent some of the most thrilling wines for the price with no shortage of emotional and cultural value. Arriving is their 2023 Piemonte D.O.C. Chardonnay ‘Charno,’ a pure Chardonnay grown on chalk and siliceous sands that immediately evokes its geological family heritage of limestone for those who regularly drink white Burgundy (but minus the new oak notes). Perhaps the star of their line in red is the 2023 Grignolino Monferrato D.O.C. ‘Poggeto,’ with which it’s impossible not to be enamored. It’s a red that’s barely red (a natural color for this red grape with very little pigment) but, like Nebbiolo, it can be deceiving with a firmer structure than expected but it always softens the blow with purity and elegance. While the Grignolino is their calling card, their 2022 Barbera del Monferrato D.O.C. ‘Giuanin’ is their economic flagship and an easy shoo-in on quality and fine tuning for those in search of a more robust but still elegant Piemontese red with bright acidity and soft tannins.

During a tasting at the cellar of Fabio Zambolin, his 2021 wines about to be bottled weren’t completely in form yet. Given this season’s woes, we weren’t sure how they would turn out, but the calamitous frost that spanked (with their pants down!) neighboring Bramaterra and Gattinara further to the east missed his area for the most part. Now there’s no doubt about where Fabio’s 2021s are headed. He may have lost some quantity, but not a step in quality. Tasted out of bottle early this summer, I was once again wowed by Fabio’s deft touch and knowhow working with his tiny parcels and his teeny tiny cellar underneath his grandparents’ house, and I was reminded of how little I know about judging unfinished Nebbiolo from vats. In my experience visiting cellars that produce Nebbiolo in a more classical way, I find this grape one of the most difficult to predict from tasting out of vat because of the structure. Some are obvious, but often times others, like Fabio’s 2021 wines, are difficult to gauge but end up being some of the most compelling wines of the vintage. Crafting Nebbiolo is really an Italian thing–must be in the blood; unless you’re Dave Fletcher!

As we’ve mentioned frequently, both of Fabio’s wines are grown inside the storied, but until recently, nearly forgotten Lessona appellation with its famous yellow and orange volcanic marine sand. But because his winery is 10-15 meters outside of the D.O.C. legal border, he’s relegated to the generic and large Coste della Sesia appellation, so this is a great terroir wine at a great price because of a technicality. In the opinion of many in his now cult-like following (which includes me), his wines are worth far more than what they cost, especially compared to other even pricier Lessona wines that bear the D.O.C.’s name. Arriving are his 2021 Coste della Sesia ‘Feldo,’ named after his grandfather who planted its vines inside the Lessona D.O.C. in 1953 on a flat surface of pure volcanic marine sand at nearly 300 meters and is a blend of 50% Nebbiolo, 25% Croatina, and 25% Vespolina. It has gobs of festive aromas and flavors (at least compared to other wines in an area known for often producing more solemn and strict wines in their youth), with not a single dash of pretension–it’s well-made Northern Italian glou glou. Its rustic, playful flavors evoke an ancient Italian culture and are perfect for full-flavored food such as cured ham, braised meat, pasta, and pizza.

The newly arriving 2021 Coste della Sesia Nebbiolo ‘Vallelonga’ is the flagship of this dinghy-sized operation. What is most striking about Nebbiolo grown in the soil of Lessona is its subtle and equally substantial aromas specific to this place. It hits all the markers expected from Nebbiolo (rose, tar, anise and great structure) but here they transcend the weight and power of the Langhe with an angelic rise of elegance from the glass. A very well-respected wine writer once mistakenly lumped Lessona into the mix of northern Piedmont Nebbiolo wines and labeled it “a rather less pure form than a great Barolo.” This oversight would be easy for anyone who prizes power over elegance. But a Lessona tasted and compared next to its regional brethren, like Gattinara, or Boca, or to a Barolo further south, is like putting a ballerina in the ring with a bunch of boxers in different weight classes. Famous Italian wine writers of late 1800 and early 1900 once considered Lessona wines to be the greatest reds in all of Italy, and in the right hands it can represent one of the most pure expressions of Nebbiolo. In Fabio’s hands, this wine is substantial but will always veer toward the side of grace as it ages.

When I’m first introduced to a new grower’s wines, I try to find reasons not to import them because we already can’t help ourselves by not overextending with our current roster. In fact, after two rounds of samples of Castello di Castellengo, I went to the cantina for my first visit to confirm whether or not I was in. I went with my longtime friend, the former importer and restaurateur, Max Stefanelli. I told him on the way there that the first two tastings were very good and that I was hoping to be let down by the visit so I didn’t have to sign them on. After Max tasted the first two red wines in the range, even before we got to their top red, the Castellengo, he leaned over and whispered, “I’m sorry, but I think you know you have to import these wines.”

Located east of the once wealthy Alto Piemonte town of Biella, and south of the prestigious Lessona appellation–whose Nebbiolo wines were once considered Italy’s finest–a unique hill stands above the eastern plain below, spared from the full erosion caused by Alpine runoff and glacial movements. This special terroir, featuring volcanic marine sands similar to those in Lessona and the eastern side of the Bramaterra appellation, is home to the organically farmed Centovigne Nebbiolo and Erbaluce vineyards, owned by Magda and Alessandro Ciccioni. Raised on the grounds outside their 18th-century castle, Castello di Castellengo, Magda (who is both the mind and hands behind the delicate yet flavorful wines) matures their organically farmed wines in concrete tanks and large oak barrels, blending tradition with modern sensibility.

Magda Ciccioni, the mind, hands and emotion behind these special wines.

It’s only a matter of time before the generic D.O.C. appellations of Coste Della Sesia (established in 1996) and Colline Novaresi (in 1994) need to be updated. Their D.O.C.s were established when almost nothing so serious was happening in Alto Piemonte to grab the attention of journalists and buyers. Today, several hectares (give or take 100) planted can only be classified as Coste Della Sesia D.O.C., but where it starts to get hairy is when grapes grown in other D.O.C.s that don’t adhere to the D.O.C./D.O.C.G. regulations can also be labeled Coste Della Sesia D.O.C. or Colline Novaresi D.O.C.

Viewing this appellation through terroir lenses, like geology and climate which, of course, both affect the choice of what varieties are optimal to plant, makes them especially hard to generalize, except that they’re far too general. There’s too much quality wine made on very different terroirs all over these widespread appellations, and while some are average sites, others are spectacular and picturesque. However, dizzying eye-candy vineyards don’t immediately guarantee the highest quality, and it’s often those that are unassuming and even boring to look at that can deliver a spiritual awakening in vinous form. Take many top vineyards of the Côte d’Or, like Chambertin and its satellite Grand Crus, or the unassuming vineyards of Brézé that electrified the wine world only just over ten years ago.

In the Coste Della Sesia D.O.C., one such grower making fabulous wines whose range easily competes regardless of price on finesse with some of the top growers in the ‘more serious’ appellations, like Lessona, Bramaterra, Gattinara, and Boca, is Castello di Castellengo.

This perfectly concise map was borrowed from winedecoded.com.au

This illuminating map was borrowed from vinland.wine

Photo borrowed from the cantina’s website, Centovigne.it

Those beautiful yellow and orange sandy soils–a near dead ringer for Lessona, at least visually.

My first taste two vintages ago (the 2019) of Castello di Castellengo’s Coste Della Sesia ‘Rosso della Motta’ made me do a double take. This wine has a shocking price–in the best possible way! It’s very inexpensive, but it’s also very serious. What it’s best at is how much joy it unfurls compared to so many other Alto Piemontese reds that have forgotten wine is also to be enjoyed; to be fruity and merry. It’s made entirely from Nebbiolo grapes harvested from 70 to 80-year-old vines planted between 300-350 meters on the rolling hills of marine sand and clay. To keep the fruit profile upfront during its two-week natural fermentation in steel, Magda keeps the temperatures maxed out at 22° C. It’s then aged on lees for 24 to 30 months in concrete without racking before a light filtration at bottling. With only 40 mg/L of total sulfur, added only at bottling, its years of refinement under all the natural bacteria, yeast and microorganisms that survived and even grew in fermentation make this a truly authentic wine, at a great price.

Despite the emotional, cultural, and fine-tuned craftsmanship Magda delivers with her flagship wine, 2016 Coste Della Sesia ‘Castellengo,’ we only dipped our toes in the water because of the current downturn of the economy. The 2015 was spectacular already, but given the choice of starting with that slightly more rustic but wonderful version or the more perfected and precise 2016, when tasted side by side, there was really no choice. If we were in the year 2013 today, during perhaps the height of Alto Piemonte’s market share, this wine could’ve been one of the most talked about in the entire region, if tasted blind–its appellation while tasting might deter people from acknowledging how fabulous it really is. Also entirely composed of Nebbiolo from a single plot of 25 years, it peaks at 370 meters but is on a steep slope. In the cellar, it’s also kept from exceeding 22° C during fermentation to preserve more fruit for its three years in old 15hl barrels. For those who love wonderfully refined and stunningly perfumed Nebbiolo in large old wood, this is not to be missed.

At this moment of our arc as importers of fifteen years, we are always looking to work more with enjoyable partners as much as talented ones. With Sébastien Cartaux and his wife, Sandrine, we have found both. And the mind behind the wines, Sébastien is equally serious about his craft as he is genuinely joyful and generous.

The first samples sent from the domaine included mostly their entry-level white wines and their Pinot Noir. From the first tastes, it was a no-brainer. The whites were classically styled without an extensive amount of funk to get me thinking about how they’d be received, and the Pinot Noir was just perfect: simple, clean, bright and fun with just the right amount of trim and architecture imposed by the terroir. A visit this June confirmed my enthusiasm and we expanded our selection to include their Vin Jaune and their lovely, bright-fruited Trousseau and Poulsard.

We made a tour through their vineyards in l'Etoile, Quintigny, Ruffey-sur-Seille and Arlay with a little droning, a little photography, lots of smiles and lots of tasting and a nice lunch where they treated us with a rare (and correctly priced) and inspiring bottle Nicolas Jacob Gamay, ‘PG’ to taste along with their Poulsard. While Jura is loaded with tiny domaines that everyone wants and few can have, like Jacob, and a few dozen others, there are ‘working horse’ Jura wines that carry just as strong a sense of place rather than an association with the producer. Sébastien’s are more related to the former and are not yet, and may never be, in that cult-of-personality line because that just doesn’t seem to be Sébastien’s way, nor interest. He’s determined to carry on a traditional style with their reds to preserve the naturally fresh and bright fruit-led aromatics with rusticity in the background, while their whites a core of acidity and firm structure led by the aromas, flavors and textures from the ancient noble practice of sous voile (under a veil) aging that highlight austerity and the floral bouquet of Savagnin and, particularly from Chardonnay from these parts.

Photo borrowed from L’AtelierTM, a designer of maps and cool designs.

Sébastien and Sandrine’s family domaine is relatively young. The family’s first harvest in 1973 on a small 0.20-hectare plot in L’Étoile, their parents, Anne-Marie Bougaud and Guy Cartaux, acquired the Château de Quintigny (whose name adorns most of the labels as well as their family name) in 1983, expanding their vineyards and fully committing to winegrowing. Sébastien Cartaux and his sister Nathalie (who left the domaine in 2010) took over in 1993, and today Sébastien and Sandrine continue to run their 20-hectare estate, which was organic-certified in 2022. They produce Chardonnay (which makes up the vast majority of the vine surface area of L’Étoile’s 67 hectares) and Savagnin from AOC L’Étoile, as well as reds (Poulsard, Trousseau, and Pinot Noir) from the Côtes du Jura. Their wines are crafted in numerous cellars, including the ancient Château de Quintigny, using both traditional “ouillage” method with air space left in the barrel and the region’s unique oxidative aging process, essential for producing the renowned Vin Jaune.

The Jura is a classic combination of continental and mountain climates, which means cold winters and potentially very hot summers balanced with cooler nights, thanks to the nearby Alps. Here, the diversity of the grape varieties makes for harvests that spread out over the season, with Pinot Noir typically ripening early and Savagnin picked later to achieve greater maturity.

Geologically, the region relates mostly to the Jurassic era, like the Chardonnay and Pinot Noir areas of Burgundy. Though here in Jura there is a lot more friable/fragile limestone marl that decomposes rapidly and holds water well, making for deep root penetration into the bedrock and offers some resistance against what can be very hot and dry summers. Also, l’Étoile gets its name from the Lucky Charms-sized star-shaped (étoile) pentacrine fossils formed from the stems of ancient sea lilies.

The white wines are a mix of different approaches but are always made in a more classical and direct way with a simple cellar approach. All Chardonnay and Savagnin wines go through natural fermentations with higher maximum temperatures of around 25° C to reduce the fruitier characteristics–further encouraged by lower temperatures–to focus on the secondary and tertiary notes from the start of their potentially long lives. There are differences in aging vessels with both steel, enameled concrete vats and ancient 228-liter French oak. All whites undergo filtration and are fined (except the Vin Jaune) and they all get their first small sulfite dose added to the must before primary fermentation and then again after malolactic.

The reds are as equally direct as the whites and tend to be focused on more upfront fruit qualities but fermented at a maximum of 33° C, which curbs their overtly fruity potential, imparting, again, more savory notes alongside the lifted fruit and flower aromas. Natural fermentations are the objective but are sometimes stubborn enough to warrant assistance. Each variety spends its élevage in different vat types and for different lengths of time, between six and 12 months.

The vineyards of Cartaux-Bougaud are planted on gentle to relatively steep limestone rock and marl sites with variations of clay, sand and silt topsoil mostly derived from the underlying bedrock, and sit between 250 and 300 meters of altitude.

Sébastien makes a few different bottlings of bubbles, but it happens that the one that strikes us the most is the starter in the range. It’s perfect for a grape like Chardonnay that only needs a good terroir to channel its minerally message in a simple and straightforward way. Like any bubbles intended to be easy to quaff without too much hubbub, the Crémant de Jura Brut (no dosage) comes from younger vines of about 15 years old (2024) planted on a south face at 250 meters altitude on gentle slopes.

Their sturdy line of Chadonnays, their appellation L’Étoile Chardonnay and L’Étoile Chardonnay ‘La Côte des Vents’ are both on an average of around 280 meters but La Côte des Vents (“the slope of winds”) comes from vines planted in 1973 on a steeper slope where the other Chardonnay is on a gentler slope with vines planted in 1983 on deeper topsoil. Consequently, the L’Étoile Chardonnay is aged under flor for 12-18 months in barrel (perhaps to round out the shoulders the deep clay topsoil seems to impart), while La Côte des Vents spends its life entirely in more inert vessels (steel and concrete) for a year to build on its finely etched lines.

Vin Jaune is an obsession for some, and one of France’s historical vinous triumphs. There are those that are ready when young with a richer, energetic profile in their youth, and those much more stoic, seeming to be born serious and built for the longest haul. So far, Sébastien’s interpretation seems to land solidly in the stoic lane, which would be unexpected once around this always jovial maker. It might be better suited for a private collector with many years ahead of them (or for their children!). However, paired by the sommelier with the right food, like its famously perfect match, Comté, it will definitely inspire the drinker to crack a smile. We might even suggest the similarly styled but higher acid, well-aged Beaufort to force a bigger grin from Sébastien’s rendition. Their Savagnin grapes for this most historic wine of France comes from vines planted in 1993 on a west face at 280-300 meters on a steep slope of limestone marl bedrock and rich clay topsoil.

The three Côtes du Jura reds hit their varietal marks with clarity. All come from gentler slopes that range from 250 to 280 meters of altitude–typical for the top Côte d’Or wines across the Saône Valley toward the west. The Pinot Noir comes from vines planted in 2006 on an east-west face, the Poulsard from two plots planted in 1993 and 2015 with east and west faces, and the Trousseau also comes from vines planted in 2006 on a south face at 280 meters. These are classic and even slightly dainty red wines with only the slightest hint of Jura funk. After a couple weeks on the skins without stems, the Pinot Noir is raised in 2/3 concrete and 1/3 old 228 L French oak for ten months prior to bottling, while the Poulsard and Trousseau are aged half a year in concrete before bottling.

We sent messages to more than a dozen growers about how things were going around mid to late September. Optimism is a crucial trait of every successful and inspired grower, but this year has put them all to the test, especially the organic and natural wine practitioners.

Another photo courtesy of Katharina Wechsler, harvest 2024!

In Southern Piemonte, Giovanna Bagnasco, from La Morra’s Azienda Agricola Brandini, said it was pouring rain on September 17th as they picked their Dolcetto d’Alba fruit. Our Barbaresco grower, Dave Fletcher, said the same thing happened when he picked his Dolcetto d’Alba fruit from Roero in the cellar just a few days before my inquiry, same with Daniele Marengo, who takes all of his Dolcetto from their high altitude vineyards in Novello. The consensus is that the Dolcetto was picked about two weeks later than in previous two years. Almost across the board was the common theme that the vegetative cycle and flowering started two weeks earlier than recent vintages. However, during harvest everything is on pace for two weeks later than expected from the typical and usually reliable prediction of “100 days from flowering” for the pick date. The advantage here is that longer seasons often mean more complexity, that is, if a new calamity doesn’t arrive before the grapes come off the vine.

Dave told me that it was a tough season from a grape-growing point of view. There was a lot of sporadic rain in spring and early summer, and some places were pummeled by hail. Mildew pressure was always high and didn’t back off an inch during the weekly rains. This forced many organic growers (as all three mentioned are) to spray copper and sulfur around sixteen to seventeen times because the weekly rain continued to wash off the treatments. He noted that this was an extraordinary amount of treatments for a single season and nearly unprecedented in his 15 years in the area. The summer was short with low thirties Celsius with warm nights, but those typically cooler nights came at the beginning of September rather than the end.

Photos, hands, and grapes (Pinot Noir from Alta Langa, Arneis from Roero) courtesy of Brandini’s Giovanna Bagnasco, harvest 2024.

All of them mentioned the upside of longer hang time for both Barbera and Nebbiolo; the latter still has the upper hand and instills more confidence in growers because of its higher natural resistance to mildew. Nebbiolo seems extremely promising to all three, but the jury is still out. August had its hot moments but quickly cooled off at the end of the month. They each said that at night in much of September, it got down to 7° C and up to 24° C during the day, which is unusually cool for the month. Quantity is low but the outlook on quality remains good. If the weather shifts and pushes Nebbiolo into October, Dave said that the season would likely end up like one of those classic vintages we read about from the 1970s, where the longevity of the wine is in the cards but they might not be as immediately accessible as the more upfront vintages of recent years, unless the producers change their cellar strategies, which doesn’t happen so much in these parts. One observation Giovanna, Dave and Daniele shared was that the phenolics continued to advance even though the sugar levels remained relatively unmoved. Daniele said, “We are very hopeful because there is enough water to have lower alcohol than in past harvests and at the same time well-ripened tannins and aromatic flavors.” Giovanna is still confident about the potential quality and health of the fruit to continue her work with whole cluster fermentation on Nebbiolo. “The quantity is not high, but the quality is very good,” Giovanna said as she added that the berries are also unusually small this season.

Fabio Zambolin said that the 2024 vintage in Alto Piemonte was one of the rainiest from May to mid-July with mild temperatures that then rose throughout August but still with frequent rains. These weather conditions led to many agronomic difficulties and the work in the vineyard was long and difficult. At the end of September there was a big difference in temperature between day and night which, of course, led to a great refinement of the balance of the grapes. It’s hard to say what kind of vintage it will be when it’s all said and done, but Fabio believes it could resemble something between the 2014 and 2019 seasons. We’ll see!

On the other side of northern Italy, the (still) young Martin Ramoser from the Südtirol’s Fliederhof said it was a similarly tough year with a lot of rain in May and June. Like everywhere else, this made their organic and biodynamic farming extremely laborious, with many cluster casualties along the way. In August it went from cold to very hot, quickly. With the enclosed series of glacial valleys in this part of Italy, the dial can get cranked up quick and it often has the second hottest summer highs in Italy behind Sicily. After the August heat, September dropped again to super low temperatures at night, with less than 10° C and raised to just over 20° C during the day. Usually through September, it stays up around 30° C during the day. Similar to Nebbiolo in Piemonte, the Schiava grapes have thicker skins than usual, and also the grapes already tasted great in mid-September but the tannins needed more time and were ultimately picked at the end of the month. So, it was on the same basic track here as in Piemonte.

In Toscana, a vigneron following a vinous path with a similar mentality to those creative footsteps of the region’s famous renaissance men, our fearless and deeply talented Giacomo Baraldo said the harvest is already going really well even if the weather is difficult (in his words, “an ‘effing bastard,”) because since late August it’s been rain one or two days, then sun, rain, then low temperatures between 9° to 12° C in the morning, which is good for slow development. The style and season will be a cooler year with lower alcohols, like 2018, 2020, and 2022; even though ‘22 was warmer, there are similarities. There was no snow this winter, only a couple of weeks with freezing nights, but not as long of a cold season as usual. Both budbreak and flowering were seven to 10 days earlier than usual, and everything pushed quickly but the spring got cold and a little wet and slowed down and remained cold until the arrival of a hot and dry July. Four to five weeks of sunny weather with no rain until the first week of August brought helpful rainfalls in August but remained hot again until the end of the month when it dropped to 7° to 10° C at night, and in September it was 6° to 7° C minimum. In September there was a lot of drizzle, so the grapes were bigger after it rained, but after a few days of wind and cold sun, they got smaller again. Giacomo believes that everything should be around 12 to 13% potential alcohol. Like our northern Italian partners, he doesn’t feel a rush because the skins are thicker this year and they’re more resistant to mildew. Giacomo expects a similarly fresh vintage with crunchier fruit, good acidity, and good length, and it might be the most similar to 2020.

Photos, meaty hands, and grapes courtesy of Giacomo Baraldo, harvest 2024. From picking, to vineyard fermenting, to the press.

In other September news, our cantina in Gaiole in Chianti, Riecine, has been sold! And it went to none other than its current wine director, the young Alessandro Campatelli. This is the first time in this cantina’s 50-year history that an Italian has owned it without partners! Of course, nothing in the wines will change as they have been under Alessandro’s direction over the last decade. This is big news for this humble and talented winegrower to become the head of his dream estate. Congratulations, Alessandro!

In the south, Paolo Latorraca from Madonna della Grazie said that the opposite was the case for Basilicata. It was too dry, and these conditions are good for the health of the grapes but on the other side it means there aren’t great water reserves in the soil now. But because the majority of their vineyards are older and stronger, their root system handles difficulties caused by the strange climatic systems. He said July was not easy but fortunately, they had rain in August and September. Aglianico has a long ripening process, so what happens for early ripening grapes is different for those who harvest well into the fall. Further south on the peninsula, Sergio Arcuri is still waiting to start the harvest of his Gaglioppo grapes for his Cirò wines, Aris and Più Vite.

Jumping over the Straight of Messina from Calabria to the north side of Etna, the season started cold and wet but once the sun came out at the beginning of summer the hot and dry weather didn’t ease up until September and the arrival of some welcome rain. Federico Graziani’s white wine, Mareneve was ready more than two weeks in advance than usual and harvested before the rainfall between the 27th and 29th of August. The white wine bunches were tiny, and the reds were also small. It won’t be a big quantity this year, but Fede is convinced it’ll be super-top quality. At the lower altitude of 650 meters, the ancient Profumo di Vulcano vineyard was harvested on September 17th, and they finished the first part of the main harvest on the 20th and wrapped up the highest altitude locations in Montelaguardia before the end of the month. This successful season is great news, especially after the 2023 frost took about 90% of his production and that of many other growers on Etna.

Nerello Mascalese from Federico Graziani’s Profumo di Vulcano vineyard. Photos courtesy of Federico, 2024.

In Lower Austria, the season started with an early budbreak and early flowering and the harvest was much later than expected – pretty much like everywhere in this report. Sugar levels were expected to be high, but fortunately, the sugar ripeness was not as fast as anticipated. Compared to the last years where the acidity was sharper, like 2021 and 2023, the acidity promises to be somewhat lower, but still higher than 2022, making for easier and earlier wines with moderate acidity. Then the flood came.

Photos courtesy of Michael Malat outside of their winery, 2024.

Michael Malat told me that when the rains hit, a state of emergency was called in Lower Austria’s Kamptal, Kremstal, and the lower areas of the Wachau. All over the lower zones vines went for a swim and some completely drowned with the fruit still on the vine! The sun began to shine again on September 17th, and the vines outside of the flood area continued to ripen. Thankfully it didn’t get hot right away after the rains, so the vines didn’t take up so much water and explode the berries as what typically happens. Grüner Veltliner and Riesling harvest for the Malats began mid-September before the rains. However, the cru sites–well outside of the flood zone–were still hanging fruit. The final pickings were made in the last week of September into the first week of October. Because of the unique weather at harvest time, Michael said there may be more play in the cellar at harvest with the tannins to bring a little more body. Overall, he expects a modest vintage with easy drinkability.

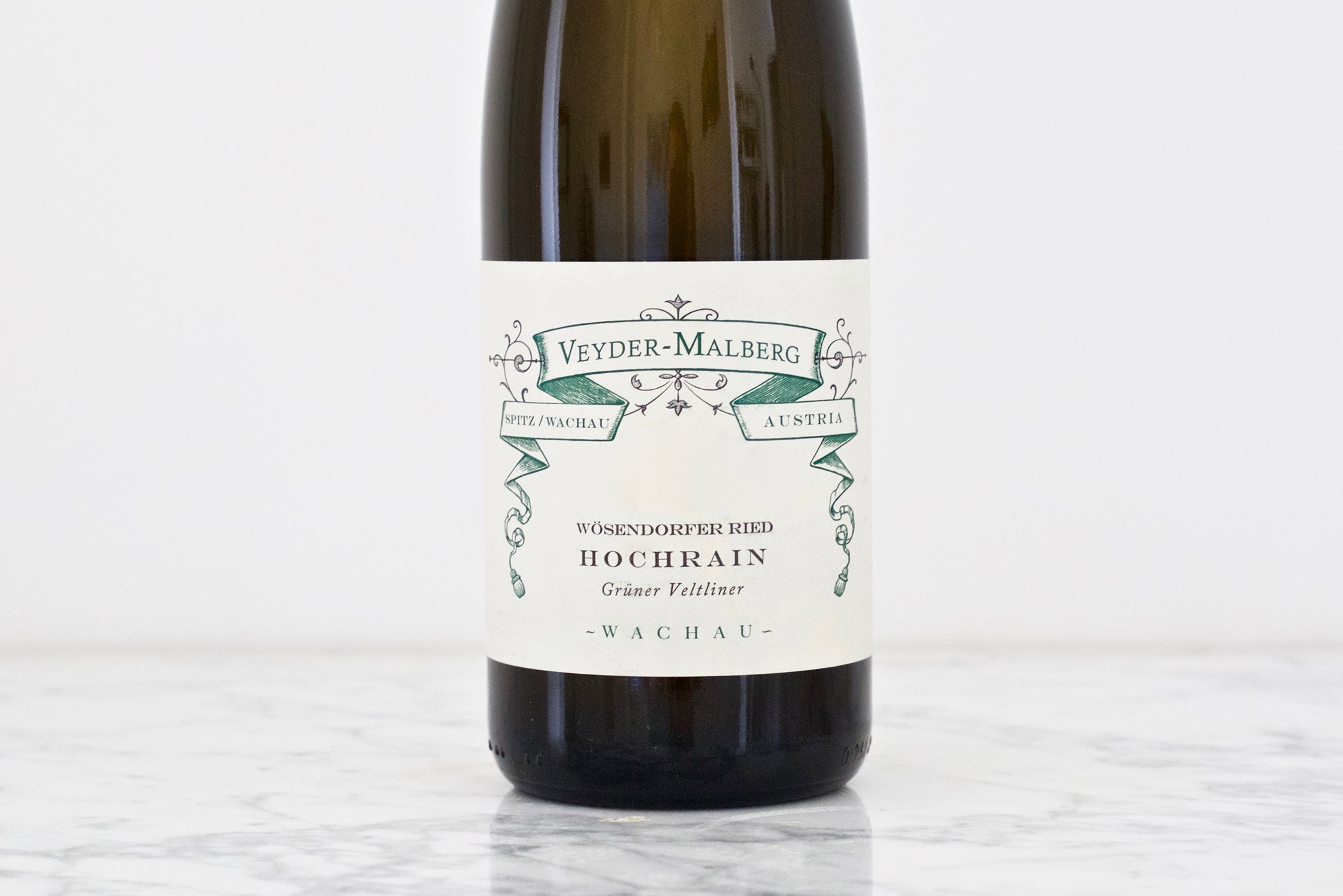

Given that he’s one of the first to pick in the Wachau, I’m not surprised that Peter Veyder-Malberg had already brought in about 60% of his grapes before the torrential rainfalls and flooding. He began picking on August 19 and told me, “The fruit was excellent!! Perfect pH. Low sugars. Fermentation without any problems. The young wines are so good. I am really happy (which I am usually not, at this stage).” Of course, he stopped picking during the heavy rains, which between the 12th and 17th delivered 295 mm, almost 12 inches–one-third of their annual average, in five days. This is a lot for anywhere, but being beside a river as big as the Danube, with its numerous tributaries also flooding before they even got to wine country, it can be catastrophic, and it was. Harvest began again on September 18th, so this year will have two vintage reports: grapes picked before the rains, and those after.

Katharina Wechsler was busy picking her Rheinhesen Pinot Noir and Kabinett Kirchspiel in the third week of September. Acidities and pH levels look to be great, but it’s too early in the game to know and the weather got warm but not hot in the last part of September. The first two weeks of harvest had some rain, but Katharina said it will mostly be an October harvest: good news for those who, like us, have a predilection for bigger acidity in Riesling! Her Pinot Noir (pictured) is also expected to be a great success!

The gents at Wasenhaus started harvest in mid-September in their Baden vineyards but got off to a slow start due to the cold and otherwise difficult weather. It was the earliest bud break they ever had, but it may also be their latest harvest. “The mildew pressure was so high that we had to bring things in earlier than we wanted, or we may not have picked anything at all from some parcels!” Alex Götze said. The calibration is different this year, because like some other areas of Europe the season is unusually longer, and well past 100 days after flowering–the common measure for predicting harvest dates. Ripeness went dormant at the beginning of September and almost didn’t shift at all through mid-September. The acidity and pH levels are great, and alcohols are unusually low, “like 2021, but better.” There’s also more fruit than 2021 (less than 2022) and they didn’t have the frost that many regions had earlier in the year. “The taste is good, but it will be a light vintage. Of course, we want the reds a little riper, but we have to take what nature gives us,” Alex said as he added, similarly to Dave Fletcher, that maybe it’s one of those really old school vintages where it’s cold during picking and ripeness is no longer advancing on sugar but grape phenolics continue to ripen.

Overall, the French regions where we work (the figuratively “cooler” ones) had a rough go of it. One of France’s greatest cultural and geographical assets is that it’s the center of Western Europe. It has the Atlantic on two sides, the Mediterranean on another, and massive mountains bordering its southern and eastern sides. Right in the center, where much of our focus is, it’s locked into the current woes of continental climate weather, which means when it’s hot, it can get really hot; and when it’s cold, it can be pretty miserably cold and dreary. 2024 was another year that continues the stress test of its organic and biodynamic growers, of which are about 90% of our French growers.

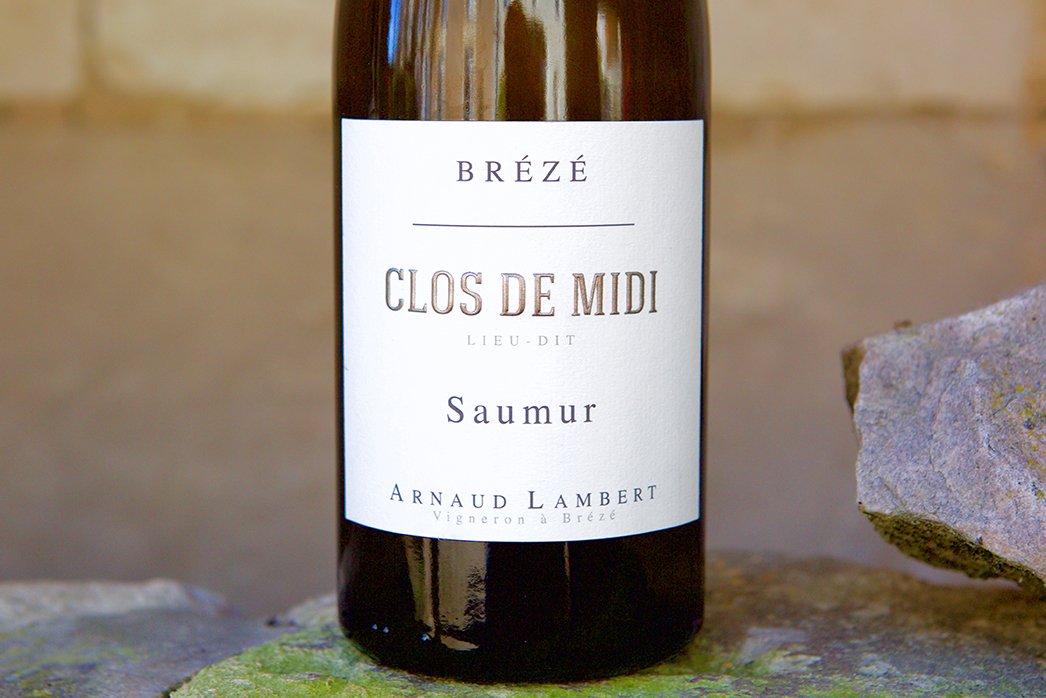

In Saumur, our friend Arnaud Lambert told me that it was good weather mid-September to harvest grapes for sparkling wines. Cabernet Franc will be harvested in October, like 2021. The Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc were both green harvested to find balance on the vine come picking time. Arnaud added that it won’t be the vintage of the century but perhaps it will end up with good overall maturity. There were rains in the last week of September, which pushed the entry-level Chenin Blanc grapes into the first week of October. Arnaud said, “All the vines were prepared for low yield, so we should be okay this year. And whatever was not ripe enough for the still Chenin Blanc wines will be used for sparkling, so I’m focusing on that.” Also, in Anjou, Patrick Baudouin, whose wines have finally just left the cellar for California at the end of September harvested on September 25th after a sizeable rain. While it presents some challenges, it also may stimulate Patrick’s favorite result: botrytis for sweet Chenin. I already know without asking that our gang in Montlouis-Sur-Loire is in the same rain-pelted boat, navigating their way toward sunshine.

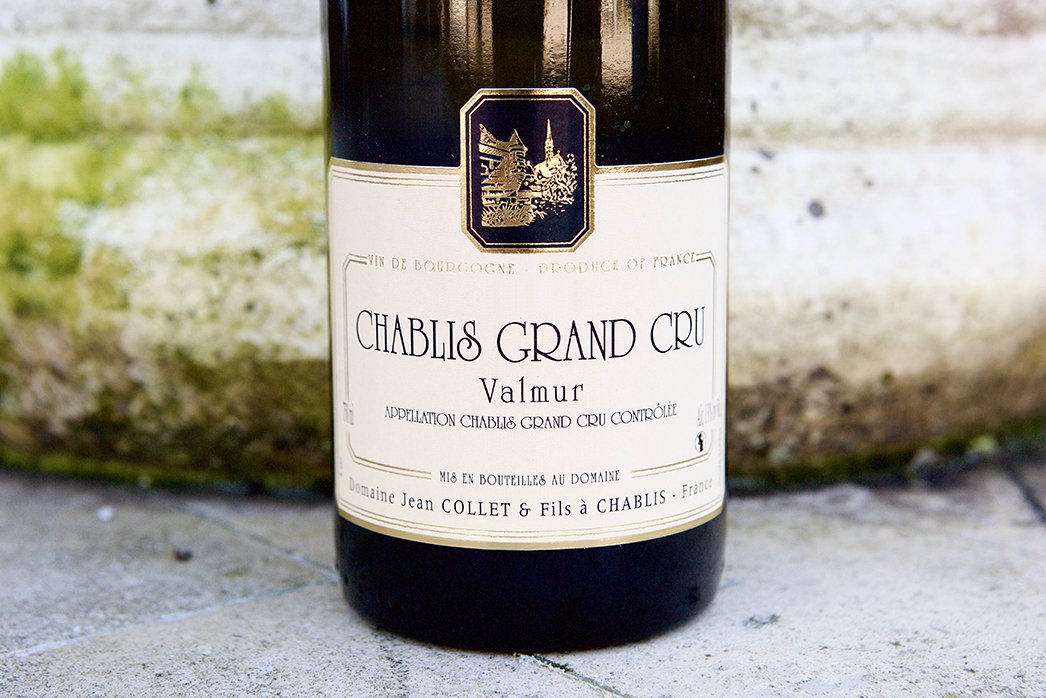

Romain Collet from Domaine Jean Collet told me that while it’s difficult to say 2024 is like other Chablis vintages at this point, it’s closest to 2021 because of the cold season and tension of the wines, and it’s also a later year. “It’s a difficult vintage to reference because there are few comparisons for the growing season. There were only 15hl per hectare because of a terrible hailstorm on May 1st and a season with big mildew pressure and the wines have a great acidity with very low pH levels. It was, like so many organic producers have said, that it was the most difficult in recent memory. Well, with those 15hl per hectare, we should have something quite nice and fresh! It’s impressive that there are two years in the last ten in Chablis that will still have classic notes while almost all the others have been much sunnier and riper.

As mentioned in the August newsletter, David Duband lost almost his entire crop on the Côte d’Or. He’s practiced organic certified farming for the last decades, but this one put him to the test. He still has his Hautes-Côtes de Nuits wines, but with their modest pricing (compared to the Côte d’Or) it will be a shock to his venture’s financial stability.

Ophélie Dutraive from Clos de la Grand’Cour just finished picking grapes in Beaujolais by September 22nd. 2024 was a very intense vintage because of the heavy rainfall, disease, and hail. The vintage is similar to 2021 but might have more concentration, tannins and structure. Just before harvest they had very nice weather in Fleurie and Beaujolais in general. Fermentations are going well, but because of the weather the fermentations are slow going, with longer pre-fermentation time. Unfortunately, in Fleurie there are only two different tanks so there will be Fleurie Tous Ensemble this year rather than the four or five domaine Fleurie bottlings.

The harvest in Rías Baixas’s subzone Val do Salnés, where we have all three of our Rías Baixas growers, said the harvest was very small because the few grapes they had were due to poor fruit set in spring. However, the wines should have moderate alcohol levels (approximately 12.5%) and very good acidity. Rías Baixas stars, Manuel Moldes and Pedro Méndez, both finished their harvests on September 24th. After what Manuel describes as a very strange summer with cold and rain first then a quick transition to hot and dry, “only a little water was missing at the end to be a perfect vintage.” Ultimately, the season was longer and calmer with time to make the choices they wanted without rushing. Manuel said, “In principle it looks good, but wine has a life of its own. The alcohol is balanced and the acidity is high. I think it’s going to be very similar to 2016, which I love, and it ages fantastically. The malics are a bit high, but it remains to be seen how they’ll integrate.” Pedro shared his optimism and hesitance, saying that it’s still too early to describe the wines of the new vintage, but he thinks it may have similarities to the 2022–given how spectacular his 2022s are so far, this is good news for all of us! He also thinks it could be a good vintage for the reds too, since the grapes arrived very well until the harvest. Exciting to have more great Albariño in the pipeline!

Adrián Guerra, former co-owner and founder of Pontevedra’s famous wine spot, Bagos, and now a collaborator with the fabulous local Galician importer and retailer, Viños Vivos, and helper/advisor at Adega Xesteiriña, believes it could be a great vintage. At Xesteiriña, the grapes were very healthy and they’ve not felt obliged to add sulfur this year.

The ringleader of Cume do Avia, Diego Collarte said that 2024 could be an exceptional vintage for Ribeiro, on par with 2015 and a style similar to the fuller 2022s and sharper than ‘23. There will be great continuity between the last three vintages. It was a well-spaced out season, with a slow and harmonious maturation. It produced musts with truly spectacular figures in terms of the relationship between alcohol content, acidity and pH. They will also finally again make a Caíño Longo monovarietal bottling. Exciting!

In Ribeira Sacra, Pablo Soldavini is extremely pleased with the results despite about 25% less than the previous year. Similar to Cume do Avia’s report, all the grapes they processed in September were in great shape. However, the labor shortages that are normal these days across Europe have put Pablo in the vines all day long with just enough time to go back and give the wines a sniff while they go through their slow, nearly untouched fermentation processes.

In Rioja Alavesa and Rioja Alta, Arturo Miguel from Artuke started picking September 16th. It seems like a great year for them. Arturo said, “The summer was pretty fresh compared to other hotter years, though we had four or five days where the temperature was above 37° C but every night in the summer was a 20° C swing with around 12° to 14° C, which was perfect for maturation. The last week of August and into the first weeks of September the skies were filled with clouds and temperatures fell to 20° to 24° C during the day, with a little rain (50 to 70 millimeters) but not much. The crop was a little higher than normal, like 2021 and 2019.”

Carmelo Peña Santana from the Canary Island’s Bien de Altura had an unfortunate result this year with losses of about 80% because of no rain, with maybe the driest winter of the last 10 years. Grapes are also small with a lot of skins and stems, so this year he’s using short maceration to avoid dry tannins. The bunches were also irregular with some fully ripe bunches beside unripened clusters. It was a hot spring and summer until August which brought a good amount of rain. He said it took a crazy amount of time to pick just 500 kilos of grapes and added, “The previous year was a bigger production and maybe it blocked a potentially higher yield for this one. But that is the nature.”

Loureiro from Portugal’s Lima Valley & Touriga Nacional from Douro. Photos courtesy of Constantino Ramos.

In Northern Portugal’s Vinho Verde area, Constantino Ramos said that it seems to be a very good season, save the rains midweek prior to harvesting on the last weekend of the month that brought some losses. Overall it’s been a very successful year given the strong final stretch after cool and wet conditions in spring and early summer. The Alvarinho was picked about a week to 10 days later than last year, resulting in richer wines but still with comparable acidity to the previous year–not a bad thing in this area where the wines could use a slightly stronger flavor profile to support the natural strength of the continental climate wines of Monção e Melgaço.

Luís Candido da Silva from the Quinta da Carolina (and head winemaker for Niepoort) said that harvest finished for his wines in Douro about mid-September. “It was a weird year in general for me but it was really good. My vineyards had a great balance between sugar and acid. I harvested Carolina with 12.7% 3.4 pH and 6 g/L of total acidity. It was an incredible year for the old vineyards. I guess it had to do with more established root systems and their knowledge about the management of fluids within the vine, which kept the old vineyards more balanced. The young ones had problems in keeping photosynthesis going during the heat and wind in this last period of the ripening season. They couldn’t get sugar they needed and the acid was dropping daily. We harvested some whites for Niepoort with 10.5% alcohol, pH levels around 3.4 and total acidities at 4.5. Normally with this alcohol level we’d get pH levels of 2.9 or 3.0 and a TA close to 8. So in general I think it will be a great year as I work mainly with very old vines my juices are super good and I'm really happy about them. They have good quantity and very good quality. The reds are super flavored, the color extract was with colors that I’ve never seen: fuchsia! And, the whites are vibrant and electric. Let’s see in a couple of months!”