(Download complete pdf here)

Etna, east Sicily’s great mother, Mother’s Day 2024.

After a ten-day trip with our LA tastemaker, JD Plotnick, we were joined in Sicily by the Canary Islands superstar from Bien de Altura, Carmelo Peña Santana. Aside from our growers on Etna, we also squeezed in a moment with the volcano’s renaissance man, Salvo Foti. We don’t work with Salvo, but he opened his door to give us more perspective on Etna. We also attended the annual Contrada tasting with many big names present where many growers showed solid progress. Even the most dogmatic of naturalists have come around in recent years, particularly on sulfites. The quality of 2021s and 2022s is high, with the 2021 winning on elegance and ’22 on juicy pleasure. But the weather in 2023 was a disaster for many, with our two new growers losing almost 90%.

Volcanic minds: Canary Islands luminary, Carmelo Peña Santana (Bien de Altura), meet Etna’s modern-day OG, Salvo Foti

We visited again with the gents at Barrus, a dream project started on southeast Etna decades ago by Salvo and Toti that had been put on hold for a while after a deal with an overpromising Italian distributor went south. The experience scared them away from the commercial wine trail until they partnered up with their younger friend, Giuseppe, in 2017. Though they produce a mere five hundred cases of wine each season (with aspirations to grow more with two new hectares added this year), they are perhaps Etna’s most unbeatable Etna Rossos in quality and price. Grown on Monte Gorna’s ancient lava flows now eroded into sand up at 550-600m, their organically farmed wines are full of life, vibrant, raw, and pristinely crafted by Salvo, with help from the well-respected Sicilian enologist, Andrea Marletta. We renewed our vows with them during a flood of interest from other US importers and look forward to the newly arriving wines this fall.

Monte Gorna with Etna’s peak looming, site of Etna Barrus’ vineyards

Our first morning was spent with the high-energy Carmelo Sofia, at Azienda Agricola Sofia. After more than a decade in the cellar of Vini Franchetti’s Passopisciaro, Carmelo and his sister, Valentina, began to bottle wine from the organic-certified vineyards owned by their father, Giocchino (on the left). Sofia’s entry-level red, “Giocchino,” is a light-colored (like Gio’s sun-kissed checks!), fresh, and fun Nerello Mascalese grown mostly on volcanic soil with 10-15% on the siliceous clay soils. The other imported Etna Rosso, “Piano dei Daini,” is more substantial and has deep volcanic textures and lifted aromas. We’ll dig in more in next month’s newsletter. (Usually laughing and keeping it light at all times, the picture of Carmelo below on the right is as serious as you’ll ever see him look. Giocchino is the opposite: quiet and calm, though he smiles a lot, too.)

A name you will see much more of among the highest level of Etna producers (and Italy in general) in the foreseeable future is Federico Graziani. This is where we started our Etna tour in May and found that he is a hard act to follow. Voted Italy’s “Best Sommelier” in 1998 at age 23, author of numerous Italian wine books, and protege of Etna’s oracle and renaissance man, Salvo Foti, Fede’s wines hit marks high enough to match some of the world’s greats.

Because it was the night before the Contrada tasting, we shared time (at least before our dinner together) with journalists filming him and droning his vineyards (which I’ve also done!). Half a dozen Italian sommeliers, some recent recipients of Italy’s “Best Sommelier,” crowded around his massive, round, and beautiful violet-tinted, ash-grey basalt table centered in the shade of three immense, ancient olive trees, the youngest of which are 600 years old and the oldest, 850. Quiet and with a gentle demeanor, he seemed amused by the attention but also exhausted after a long day of entertaining. Eventually, the groups went to their dinner spots, and we lit a fire in his home away from home (most of the time he’s with his family in Marche). Fede prepared a delicious impromptu broccolini pasta (and we were stunned by how delicious it was despite being so made on the fly), along with some slow-roasted clay-pot chicken and numerous great bottles of vino.

Federico is one of the most talented growers we’ve picked up recently. With more new additions like the well-known Bien de Altura and Martin Muthenthaler along with others that will be mentioned later in this newsletter, it’s been an extraordinary year already with more to come.

Let’s start with Fede’s unique blend of international and local white grapes harvested from vines grown at a frosty 1200 meters. Mareneve is sublime and seems destined to perform at its peak potential in slightly formal, relaxed, and quiet environments, perhaps even best suited for Michelin star-style restaurants—an environment familiar to Fede, the former lead sommelier in a Michelin three-star, among others.

Mareneve is an unusual blend of 15-20-year-old Carricante (30%), Gewürztraminer (25%), Riesling (25%), Chenin Blanc (15%), and Grecanico (5%). To borrow from his website, Fede calls it “crystalline alchemy.” He says, “Mareneve is the result of an idea as simple as it is bold, that of planting a vineyard at extreme altitude [on the northwest side of Etna!] to ascertain how the vines react to cold climates and volcanic soil at high altitude. Mareneve is a wine that defies time, overcoming the contradictions of an extreme terrain. It is sinew, skin and bone, with a biting acidity, a persistent salinity and a strong-but-measured personality.”

It’s fascinating, and from grapes most of us would never imagine on Etna. Fede explained that he thought the Gewürztraminer would bring the wine down, and it may initially cause hesitation for some with an aversion to the grape. “I don’t like this variety very much,” he said but then explained that it’s sort of the unifier of these different worlds (Germanic, French, Sicilian) and may be the most crucial grape in the mix. It’s noble in aroma and taste, versatile, and unexpectedly harmonious. It’s a must-try and another example of how blended grapes can express a terroir’s personality just as well as a single-varietal wine.

I’ve had about four bottles of the 2021 Mareneve so far, and it’s consistently slow to start, especially if it’s too cold, but quickly stacks one layer on top of the other in time. It’s naturally fermented in steel at a maximum of 23°C (a good temperature to curb fruit and focus more on other typically secondary and tertiary characteristics), then aged 20 months in steel on the lees with a light filtration before bottling. It’s usually decked out with soft white fruits of pear, skinless green apple, leechee, gentle spice, slight petrol, vinyl, delicate fresh chive and lime leaf. It tastes like all the fine points of these varieties forged into one flowing current. Other notes that develop are acacia honey aroma (rather than taste, which is often aggressive), dried fennel flower and fresh orange blossom. Gewürztraminer adds more flesh after some time but remains tightened by the Riesling aromas. The local varieties have their voice but seem more dominant in the texture and ashy reductive elements.

Fede’s three Etna Rosso wines are fabulous, a stylistic marriage of Salvo Foti’s Vinupetra and the best of Vini Franchetti’s Rampante and Guardiola. But Fede’s also speak the language of the most soulful, classically-styled reds: harmoniously spherical, full yet light, direct, complete, and seamless—in the palate line of those like Collier la Ripaille, Bize Aux Guettes, B. Mascarello & G. Rinaldi, Castell’in Villa. But each rosso has a singular expression relatable to other greats you may know.

Fede’s starter Etna Rosso is gorgeously polished. Raised for twenty months primarily in steel with a small portion in 500L old oak and is racked three to four times. Each of his reds are fermented with up to the low 30s Celsius, which tends to alchemize tense and lifted fresh fruit to richer, deeper, slightly steeped and perhaps less precise fruits alloyed with savory, earthy notes. It comes from 15-year-old Nerello Mascalese (90%) and Nerello Cappuccio (10%) in one parcel of Montelaguardia and two in Passopisciaro on north-facing gentle volcanic slopes between 600-800m with shallow sandy and rocky topsoil. It starts with a bit of reduction (the attractive Fourrier-style) but quickly blossoms to lifted red and dark red fruit, strong mineral textures and greater length to its elegant finish.

Young Etna Rosso vineyard at 800m altitude inside Contrada Montelaguardia

Rosso di mezzo, the second Etna Rosso up is harvested from 35-year-old Nerello Mascalese (80%) and Nerello Cappuccio (20%) vines in the Contrada Feudo di Mezzo in Passopisciaro. Facing north on a gentle slope at 600m, the volcanic bedrock is covered with medium-deep sand and rock topsoil. It’s vinified in steel with the majority continuing for 20 months, also in steel, and a smaller portion in 500L French oak.

When I first tasted the 2021s in November, I preferred the entry-level Etna Rosso (if you can call it that) over the Rosso di Mezzo, but after a few more months in the bottle, the Rosso di Mezzo surpasses it and stuns with purity. The Etna Rosso is beautiful, but last month the bottle of Rosso di Mezzo I had was fully unlocked from the get-go and pulled away through time when tasted next to the Etna Rosso. It was hard to move on from Rosso di Mezzo, even if Profumo di Vulcano was next in line. Rosso di Mezzo is the first wine in the range that takes one to the stratosphere with echoes of the most compelling examples from growers like Rougeard (clean versions), Fourrier, and Rousseau (more of a 1er Cru Les Cazetiers than Grand Cru, but after two hours open when free of their commonly oaky start). Overused winegrower clichés are certainly not in the spirit of these wines and their emotional currency. Take your time with this one.

Profumo di Vulcano’s 800m altitude ancient vineyard in Passopisciaro

“Garden wine” is what Federico calls his Profumo di Vulcano, his top wine. Mostly because it’s a mix of many different varieties in a garden-like arrangement (see the picture). But the world’s best wine grapes do indeed come from a garden-like treatment, hand-tended and respected one vine at a time rather than mass-farmed rows managed by people with no connection to the final wine.

(Even here in Portugal’s Lima Valley, the local co-op makes honest and unusually inexpensive wines for the price made from local farmers’ grapes grown surrounding their gardens. The Lima Valley’s mouth-staining beastly red, Vinhão, is rough for first-timers but beautifully rustic. The local co-op’s version from Adega de Ponte de Lima is basically free compared to other authentic wines, worldwide. Isabelle, the woman who sometimes cleans our apartment, grows Vinhão and makes wine, too—she collects all of our used bottles to bottle her wines. She once brought me Loureiro Tinto and Vinhão clusters and a bottle of the previous year’s wine. I asked if she uses any synthetic treatments. Her face flushed and tilted, perhaps in disgust, and then with a chiding tone she said she would never use such “stupid things” in her garden. Maybe it escaped her that I have to continually remind her to stop cleaning the oven or any part of the kitchen with chemical cleaners other than soap and water. A reasonable ask, no?)

What vineyard not hand-worked like a garden could produce a wine of extraordinary quality? Very few. A dense population of non-human living residents is required to arrive at the highest potential. There are those like Vinhão that are inspiring for nearly the cost of the glass bottle alone—at least for some people. And those with big price tags for which we find more excuses than justifications for time and money spent. But Profumo di Vulcano is a no-foolin’, well-worth-the-price wine. It’s a moving experience. I recommend sharing it with fewer people to experience its extensive offering over some hours. It’s never static, and one short moment isn’t enough.

My latest bottle was in June on a balmy, wet, electrically stormy, romantic night and the wine surprised us when it immediately bolted from the glass. The bottle had sat upright and unmoved for two months at cellar temperature—the right pre-game stillness and degrees for this kind of wine to be served. Other bottles were calmer out of the gates or rather less resolved in the first moments of resurrection after bottling, but this blossomed in time-lapse speed with fiery and effusive perfumes of fresh-picked, sun-warmed strawberries, sun-wilted but still living red and orange flowers; the crescendo, a pure and divinely pungent Grenache-like monologue of the Châteauneuf-du-Pape of old: tempered on alcohol, refined yet forceful; the type of wine that may have raised the eyebrows from the likes of the late Jacques Reynaud.

Further in, the structure builds. The first act of fruit and flowers recedes, and the deep, savory notes of wild, high desert-blooming thyme, austere mint, cistus, saffron, and darker-tinted fruits take center stage. For the third act, ferrous volcanic palate-staining petrichor that sharply refreshes and tightens the ever-expanding nose evolved to dry allspice berry, Kashmiri chili, green and dry smoking tinder with gamey wild meats along with lightly burned vegetables to sweeten the ensemble. Act four, regret: 750s are too small for wines this good. Act five, winesearcher.com, or hit us up for more.

On the second day, it’s equally attractive but with a juicier palate. Impressive all the way around, it gets even closer to the greatest of the greats. Think a volcanic wine touched with the spirit (and quality) of the Rousseaus, Abattuccis, and Salvo Fotis of the world, and you’ll already mostly know this wine without yet having your first taste.

Profumo di Vulcano comes from 70-130-year-old vines with an average of 100 years (some pre-phylloxera) grown in shallow sandy and rocky volcanic topsoil. The blend, Nerello Mascalese (75%), Nerello Cappuccio (15%), and 10% of Alicante, Francisi, and about forty plants of Carricante, Grecanico, and Minnella, rests on a north-facing gentle slope at 600-650m. When picked, it’s completely destemmed and naturally fermented without temperature control (which may play a part in the red-orange fruit and flower profile as opposed to fresher berry fruits, the latter often a result of lower temperatures) for two weeks. There aren’t deliberate extractions that may be sensed in its absence of a single bit of slack. It’s then aged twenty months in old, 500L French oak. Finally, the title card tech notes typical of the most full-of-life red wines: no fining, no filtration. 100 points. I jest … 20/20, probably.

Like many others, Austria’s wine regions are going through regular climate dilemmas. It’s well beyond just hot weather these days as they were also hammered with frost in 2023, and again this year, 2024, some growers lost nearly everything. This year’s big frost happened in mid-April while the shoots were very short, so there’s hope for some recovery. Weszeli and Malat were hit hard while for the Wachau team, it was less severe but still noteworthy.

2022 Riesling and Grüner Veltliner are solid, a little fuller and more broad-shouldered than 2021 and 2023. The 2022s seem more universally appealing.

2021 and 2023 Austrian Riesling and Grüner Veltliner may be more appealing for some of us in the trade because of the tension, while 2022 is likely more what the general wine consumer wants because they’re more robust, perhaps with the feeling that there’s more wine in the glass.

2022s next to 2023s are a difficult juxtaposition for high-toned aroma and mineral hounds. However, many 2023s tasted at this time were just bottled which always brings lift and increases intensity while also hollowing them out a bit for the first few months. I don’t think 2023 is at the same high level as 2021, but it’s still clearly successful and with perhaps greater immediate appeal. That said, 2022s inside the Spitzer Graben, off the main path of the Danube wear their acidic freshness like a cooler vintage.

Davis Weszeli set in motion some brilliant moves, starting with hiring Thomas Ganser in 2015, followed by organic certification achieved by 2019, and Demeter in 2023. You can taste these practices in wines expanding and overflowing with hundreds of subtle nuances trickling out over time. All the cru wines are aged a remarkable three years in large oak barrels, making the winery unique, with a big investment in piquing our curiosity and pleasure as much as theirs.

Martin Mittelbach from Tegernseerhof shows no signs of slowing down on his ascent in the ranks of the Wachau. We tasted the ‘22s and ‘23s side by side with the always-energetic Martin and everything was exquisite. We are nearing our fifteenth season working together and there are few growers I know with greater consistency, whether in so-called great or average years. And now that he’s working organically, the wines have improved overall complexity and breadth. We are in talks to have him return to the California market early next year to show the 2023s. Fingers crossed!

Michael Malat moves so quickly in the cellar that he also looks blurry to the naked eye

Michael Malat has produced yet another beautiful set of wines in 2022 and 2023, in line with earlier comments about the deep and shouldery ‘22s and lifted, flirty ‘23s. It’s difficult for me to find other growers’ wines as complex as his and that I also want to gulp down like they’re water from the fountain of youth. They’re different from other Kremstal wines, with their charming exotic and tropical yellow fruits (that uniquely match the yellow of the label and foil), spice, and refreshing minerally palate dosed with plenty of acidity, and I theorize that it has to do with their ancient cellar, which is over three hundred years old and tightly packed with heavily patinaed 40-60-hectoliter fuders with more than half a century of wines having passed through them, all seasoned from its ancient yeasts and good bacteria. I love the line and continue to feel that few in Austria make such charming wines as these.

So much can be said about Peter Veyder-Malberg and his wines, as it was in last month’s newsletter (and many times before)! During our visit, we tasted a few 2022s from bottle (though I had already experienced the entire range some months before) and 2023s out of vat over a welcome light dinner, post Sicily, on his perch overlooking the terraces of Schön and Bruck. His 2022s are more open and lifted than the 2021s. The 2023s were hard to assess in their unfinished state fully but are sure to be in line with the success across Austrian Riesling and Grüner Veltliner territory. Peter’s 2023s seem to be a stylistic cross between the ethereal and minerally 2021s and the fuller but open and complex 2017s.

I didn’t know Peter’s now making beer and apricot jam, too. You have to go for a visit for those. They’re both wonderful, which isn’t surprising coming from the hands of this wizard.

Epic beer and jam now, too? How much can we get? Sorry, not for sale … (Peter on the left, JD on the right.

Our new grower and a protegee of Peter Veyder-Malberg, Martin Muthenthaler, will soon finally have a solid presence in California. (His wines have mostly sold in New York over the last decade.) We’ve landed him for the country as our only national-exclusive Austrian grower, and what a grower to have! His 2022s were truly second to none, and they taste more like other top grower’s 2021s. All his wines come from Spitzer Graben vineyards, the coldest area of the Wachau. The range is extraordinary and his commitment to quality and full-time hand work in his vines and cellar is unlike any other top grower I know in the Wachau. Nearly a one-man team, he was only recently joined by his new Bavarian wife, Melanie, who now works in the vines and helps on the commercial side. Muthenthaler’s range is serious and undoubtedly in the company of Austria’s elite.

The Loire remains a center for not only low alcohol, fresh wines with great value, but it’s also an epicenter for the natural wine movement and home to some of the most compelling wines in France. However, I remain perplexed by the continued attention on so many Instagram-anointed, minuscule production natural wines from these parts, and elsewhere, that all too often fall shorter on expectations than supply.

Many globally overhyped and overpriced new winegrowers have done a stage, or two, or a two-week harvest at some famous winery (often in Burgundy) and are then touted to be the next “big thing” in their region, regardless of experience with their own vineyards. There are many less well-known natural winegrowers outside of the Insta-wine world as natural as those guaranteed to triple the like count on a post but are made with more astute technical precision (and guaranteed to get you half your normal likes, or fewer). I know, shiny new things everyone else is excited about are exciting. Quirk is cool, too. Especially the noble quirk of Jura. (Did I just coin that?) But there were already many competent Quirk Lords outside of Comté country before the natural wine movement hit the mainstream. When they deliver, unicorns are even cooler, especially when they’re not marked up twenty times the ex-works price in the secondary market. Even if these famous cult natural wines stink (figuratively, and literally), people may still at least want their money’s worth when they post them for the status of having had them, often without an honest take, thus continuing the cycle of undeserving overhyped wines. Are we brave enough to start to tell it like it is when a cult-famous wine is no bueno, and give more soundly crafted but less famous diamonds credit for being diamonds, regardless of their likes count?

But what’s even way cooler is schtick-free, skillfully crafted wines made naturally and with intention but without the dogma doodoo. I appreciate abstraction and quirk in wine, but serious winemaking and other artistic endeavors should have a coherent delivery.

Don’t get me wrong. I believe natural wine is the most important movement since wine began to redefine my life twenty-nine years ago.

The natural wine movement didn’t start as a rebel-without-a-cause insurrection but a logical pursuit to rediscover more natural ways of releasing a terroir’s entire voice while consciously respecting the land’s health and life in all forms. The natural wine movement is different from organic and biodynamic movements in that it was able to shuck the tight seal of the historical hierarchy in the style of the wines, many of which were a break from classical structures. However, when natural wine arrived in the mainstream, craftsmanship was neglected by some snake-oil natural-wine evangelists and less skilled dogmatic winegrowers throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what stuck and standing by their misfires no matter how awful the result with: “This is the way it’s supposed to be. It’s natural wine.”

A resonant line in Sol Stein’s Stein on Writing is, “The biggest difference between a writer and a would-be writer is their attitude toward rewriting. (…) Many a would-be writer thinks whatever he puts down on paper is by that act somehow indelible,” which is categorically false. The same could be said for a would-be winegrower, natural or not. Admit when you’ve made mistakes, learn to do better and then apply it.

The concept of natural wine done by hand (and even more, with regenerative farming) is the most logically sustainable ecological approach to making wine (except that there’s nothing about selling that natural wine that’s sustainably ecological, especially if it’s shipped across the globe). For our health, as natural as possible seems an obvious non-argument, too; except perhaps the unfair mob villainization of added sulfites in wine. How did added sulfites become the main evil, natural or not, with organic and biodynamic growers often spraying two to four times as much copper and sulfur in their vineyards, often administered by fossil fuel-powered tractors?

But I would ask why anyone wouldn’t want wine to be as free from unnatural (and natural) inputs as possible. (Natural inputs can unnaturally distort wine, too.) Like any terroir idealist, and naturalist, I want the influence of nearby forests with its indigenous wild herbs, brush, undergrowth, and trees and their inhabitants, the bug-transported wild yeasts, soil bacteria, mushrooms, etc., along with a wine’s architecture imparted by the topsoil, bedrock, weather, and healthy vines well adapted to the specific conditions of the place and cultivated responsibly. Just the good ones, please.

The end of May closed off a very rainy start to the year in the Loire Valley. The growers continued to struggle through the last week of May and early June as the rain slowed but it remained cold. Only a few days were above 23°C, at least in the central Loire. But this could shape-up to be a great season if the weather stays cool and less damp.

This four-day Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc adventure was one of the top short legs I’ve been on in this part of France. It gave me the emotional uplift I needed in the face of these less certain times. I hope it gave JD, my travel partner, the same.

The birth of 2024 in Vincent Bergeron’s Montlouis-sur-Loire Chenin Blanc site, “Maison Marchandelle.”

Since the beginning of our importing life, we’ve had a decent foothold in the Loire Valley, which started with our remaining Loire flagbearer, Arnaud Lambert. We started with Arnaud and then visited a series of growers in their second year with us, like our natural wine Montlouis team of Hervé Grenier (Vallée Moray), Vincent Bergeron, and Nicolas Renard. We also nabbed a new one over there by Montlouis, working organically since 2019, just over thirty years old and making inexpensive, solid by-the-glass wines on silex, limestone and clay, Thomas Frissant. More on him in the fall!

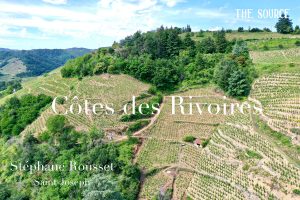

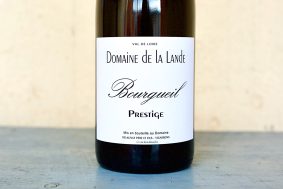

We also stopped by Domaine de la Lande to confirm our suspicion that François and his organic Bourgueil (certified since 2013) are the real deal. As mentioned in last month’s newsletter I bought four mixed cases of old wines and have since tried every vintage he sent. I tasted most with winegrowers, who all asked me to fetch as many old bottles from François as possible—names like Constantino Ramos, Manuel Moldes, and two other high-caliber growers in Rías Baixas, Eulogio Pomares (Zarate), and one of Forjas del Salnés’ cellar masters, Angel Camiña Seren. Our tasting in the cellar was a masterclass of wines made from different terroirs that all get blended into the single appellation bottling in the by-the-glass price range. Bourgueil is undervalued, and François’ wines are far too impressive for the prices. The old ones must be tasted to believe.

Forteresse de Berrye continues its rise. Gilles Colinet, the new owner since 2019, is committed and the new wines are a solid uptick from our first imported wines. On his team now is Arnaud Lambert’s long-time enologist, Olivier Barbou, and in the vineyard, Loïc Yven, the former chef de culture for the new Nady Foucault-consulted project, Domaine les Closiers. The vineyards are gorgeous and the potential is as big as it gets in Saumur, if terroir is a guide.

And, after all the ranting above, we have three “natural-ish” Loire winegrowers—all are new to the US market and mega-doozies, though two of them will arrive much later.

Arriving this month is Domaine Les Infiltrés, created and run by the timid but wonderfully enthusiastic and charming Frédéric Hauss, a former cinematographer who worked extensively behind the camera for the big screen and TV. Fréd is near my age (30, take 16; I’m on 30, take 18), but wanted a change of life into something equally artistic but more connected to nature. (Relatable?) Given that 2021 is his first vintage growing grapes and making wine, what he’s put to bottle is flabbergasting. He may have little experience in winegrowing so far, but it doesn’t show. I wouldn’t call his first vintage beginner’s luck either. The 2022s are even better, and you would surely know it wasn’t luck if you’ve tasted his unfinished wines in the cellar. Some people are quick to understand fundamentals, perhaps those who already mastered them in another craft are advantaged. But it’s clear that Fréd already understands artistic composition and how to craft a wine to capture emotion, discreetly.

Fréderic is based out of Saumur Puy-Notre-Dame, which will be a new focal point for Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc in the face of climate change; it’s colder down there. It’s also prime vineyard real estate whose grapes are mostly sent off to the cooperative—à la Brézé before we shouted from the rooftops of this hill’s potential with the simply made but potent wines of a young Arnaud Lambert, in 2010, followed by Guiberteau in 2012. What’s important in this emerging Saumur area is to find those sites on the top of hills or in the upper-middle areas where vine roots are in close contact with the tuffeau limestone bedrock, like the wines Les Infiltrés, and Forteresse de Berrye.

I enjoyed what Fréd wrote about his project, about himself. It’s in French, so I asked a friend for help translating it, then tidied it up. We also checked with Fréd to see that he approves of the translation. He’s very particular, and thankfully he did.

A picture of Fréd’s face is notably absent from our website and this newsletter. You will better understand when you finish his text.

“Believe what we feel. Act accordingly.” - “Maintenant,” by comité invisible.

My name is Frédéric HAUSS

Since 2021, I have been guiding three hectares of vines whose fruits I transform into wines, between Doué in Anjou and Le-Puy-Notre-Dame in Maine et Loire (49), in the extreme south-west of the Saumur and Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame.

I grow Chenin, Chardonnay, Cabernet (Franc and Sauvignon) and Grolleau.

But in reality, I had branched off…

I left a comfortable situation as a senior technician in the cinema in Lille, a city of heart, to take care of a piece of land with organic farming, and for 20 years I was a committed and enraged social and environmental activist. By evolving in these environments, I learned to identify models of the past that seriously compromise our future. These include agro-industry and the pressure it imposes on agricultural income, the race for equipment, expansion and debt, land pressure, the monopolization of resources, the disappearance of the peasant world, synthetic pesticides, and the death of the soil.

To speak from agriculture and out of phenomenological concern and to save the environment, I decided, like many, to occupy it…

I spent my childhood and adolescence between Orléans and Angers. A true child of the Loire, joining its banks seemed obvious to me; memories of hide-and-seek with my brother in the small Gamay plot owned by my grandfather, an amateur winegrower in Chalonnes-sur-Loire. Later, sweet emotions during tastings in Burgundy near Auxerre (Chloé Maltoff in Coulanges la Vineuse, Domaine Richoux in Irancy, Domaine de la Cadette in Vezelay, the Chablis geniuses De Moor and Patte-loup, especially the meeting with what is known as a bifurqueur (young graduates from major schools who radically change paths) before the time: Pierre Hervé, a former schoolteacher who converted to winegrowing in the hills of Tannay directed me towards vines and wine. A duo of former colleagues who went to make wine in Ardèche (Domaine les Bois Perdus), also greatly inspired me.

Wine and cinema have many points in common: the clever balance between technique and emotion, two artisanal rather than industrial professions, two areas in which our country excels and where two fundamentally opposed forms of economy coexist but are not exclusive. They are also two arts of circumstances:

Just as a film can be a reflection of the mood and logistics of its filming, a wine is marked by our harvest environments, the flashes of ingenuity with the breakdowns of the press, instincts sharp as the unavailability of a racking rod, the radical decisions as much as the compromises.

To paraphrase Baptiste Morizot in his book “Manières d'être Vivant,” grapes transformed into wine seem to me the perfect playground for forging alliances with the plant kingdom, for practicing diplomacy with non-humans. Finally, as Antonin Iommi-Amunategui (creator and host of the blog “No Wine Is Innocent”) underlines in his ‘manifesto for natural wine,’ those who, courageously, at the margins, develop wines without artifice and provide “the clear key to other battles.” So I wanted to be … Besides, Jean-Luc Godard claimed that “it’s the margins that hold the pages together.”

So much for the mind.

Concretely: Harvests at the Grange Aux Belles in 2019, a professional baccalaureate in 2020, an internship at Mélaric, the flagship of organic wine in the south of Saumur and great meetings at the right time made me settle in 2021 in the middle of unique personalities (and always ready to be of service) who revolve around the Saumur-Puy-Notre-Dame appellation (Mélaric, L'Austral, Manu Haget, Thibaut Stephan, Thibault Masse, La Folle Berthe, Jonathan Maunoury, …).

It was a smooth transition and installation, step by step; as the rapper Oxmo Puccino says, “From prestige to burlesque, I manage, with what life suggests to me.” I rent the vines and benefit from a library of C.U.M.A. material (Coopérative d’Utilisation des Matériel Agricole).

But above all, I share a tractor, van, pump and press, grape harvesters, doubts and certainties, joys and setbacks with a winegrower who settled at the same time as I did in the same area: Charlotte Savary Fulda (Vins les Coquilles). Compared to what I call “my sister vineyard,” our farms are distinct and our wines are very different. But you'll often see us stuffed together. Our relationships link common logistics, mutual aid, Adelphia, care and philosophy.

Finally, between two green jobs, I perpetuate my activism against agro-industry within the Confédération Paysanne or Les Soulèvements de la Terre. The neighboring Deux-Sèvres department has been the scene of struggles over water usage, which I consider historically significant for the world. This commitment along with many others is a salutary collective counterpoint to the solitude of our professions. It also requires me to exercise a form of discretion. I shun social networks and avoid photos. I aim to make wine like Daft Punk made music: without ever investing in my image. As one of my colleagues says, “Everything must be in the bottle.”

The estate is called “Les Infiltrés” [The Departed] like the film by Martin Scorsese, a work at once nervous, tense and elegant: a horizon for the wines that I try to develop, literally without filters, without artifice–it is also a nod to my previous job and to an environment that I infiltrated three years ago [2021] when I knew nothing about it at all. I wish the word “Infiltrés” was feminized, to pay tribute to all the women who help me daily. From my lover to the seasonal people who help to select young shoots from the vine, from my participatory financiers to the harvesters, from the winegrowers allied to the wine merchants who trust me.

In the vineyard, I’m certified in organic farming and work as carefully as possible on yield management (pruning, de-budding and shoot selection in two passes, sometimes three, as in 2023 … difficult!!!) and I plow only according to the vigor and other signals sent by the plant. No systematism. Climate change forces us to be on permanent alert. I already combine copper with herbal tea sprays (nettle and horsetail). Yarrow and valerian for periods of stress (frost, drought). Manual harvest, obviously. And perennial. Every September I like to be the accountant of the life brackets we arrange with our buckets and secateurs.

In the cellar, I work with native yeasts, my nose and mouth as compasses, the microscope as a crutch. If, in the cinema, a few tutelary figures have always intimidated me, in the world of wine, my ingenuity and my relative ignorance of the codes to master or the “100 vintages that you must have tasted” afford me great freedom. “Act like so-and-so…” isn’t really part of my vocabulary. Nevertheless, I seek to make fine, delicate, digestible wines. With bubbles and whites, I look for purity, clarity and radicality, even if it means getting close to the vegetal (should we really forget that wine comes from a vine?!). On the reds, delicious fruit, freshness: short macerations, sometimes whole bunches. I shy away from sophistication a little but recognize in the wood of old barrels its quiet and centuries-old way of magnifying certain choices.

Sometimes I sulfur in homeopathic quantities to correct a deviation or an air intake during bottling. That said, my wines do not display more than 25mg/l of total SO2 when the regulations allow 100 to 150.

This sulfur story is complicated: I admire those who make no compromise but I have decided to put my radicalism elsewhere.

On the pins, each label has a distinct illustration to mark the uniqueness of the vintages. The quotes that accompany them guide me every day, as horizons of revolutionary lives that I modestly try to transmit to my drinkers. They adapt well to work in the vineyard and the cellar, evoking serious, determined paths, always questioning …

Raging Bulles comes from a 0.3ha Chenin Blanc plot planted in 1962 at 70m facing north-south on a gentle hill of limestone bedrock with shallow silty clay topsoil. Its natural fermentation is in fiberglass for 15 days then bottled on lees with a bit of residual sugar to create natural CO2 and aged for five months. It doesn’t go through malolactic and is neither filtered nor fined. Sulfites are added (15mg/L) at disgorgement. No dosage. According to Frédéric, this wine should be seen as functional and refreshing, to be consumed with or without moderation, with friends after a long day of working in the heat. For both white and sparkling wines, he likes his to bring a side punch, an uppercut, with balance around the tension. The 2022 vintage offers a full mouthfeel linked to the few grams of residual sugar but the tasting ends with a liveliness partly brought back by the absence of malolactic fermentation. Its aromatic palate focuses on citrus fruits as well as notes of pear. An ideal drink as an aperitif or a transition between two wines or dishes.”

In a region now better known for cuttingly intense dry wines, the 2022 Saumur Blanc “Une Histoire Vraie” is the most delicate and intricate of all Chenin Blanc wines we import from Saumur. 2022 was a warm year (well, it was hot …) and all the wines are a bit softer. Fréd picked early and worked gently to capture the essence and tension of this small organically farmed 20-are Chenin Blanc plot planted in 1990 on a slight east tilt of Turonian green chalk bedrock, and deep silt and sand topsoil. After its 60-day natural fermentation in fiberglass at 20°C maximum (similar to his Chardonnay vinification, a temperature that imparts nearly equal voice to fruit and savory characteristics), it’s aged on lees for six months in old 228L French oak and then six months in bottle. It passes through malolactic fermentation and is neither filtered nor fined. The 20mg/L of total sulfites added only at bottling renders this wine even more fine.

Over a few hours, a bottle in June started on the wider side and slowly became more vertical, lifting its freshness even higher. It’s wonderful alone but would be dangerously good with sea fare like cuttlefish and calamari on a plancha, and fatty fish, like turbot or sea bass, left with the skin on—sweet and crunchy brown, finished with a touch of sizzled almond brown butter, a squeeze of lemon juice and dusted with the zest. Rarely would I think about dry wines with dessert, but with its yeasty, pastry, soft spice notes, it may also go well with a mildly sweet one such as apfelstrudel. After about four hours open, it keeps getting better, tightening more, and releasing floral notes and high-toned spice. Stylistically, think of a marriage between the wines of Anjou’s Patrick Baudouin and Montlouis-sur-Loire’s Vincent Bergeron. The next day, it was tighter and almost completely vertical. It’s a journey but hard to leave alone long enough to see those wonderfully tight-knit floral aromas.

Chardonnay “Itinéraire Bis” comes from a flat plot planted in 1992 on a Cretaceous limestone bedrock with a deep silty clay topsoil. It passes through a 20-day natural fermentation in fiberglass at 20°C maximum, the medium temperature making for a Chardonnay with a balance of fruitiness and savory qualities. It’s then aged on lees for six months in 60% sandstone amphora and 40% old 228L French oak and passes through malolactic fermentation. It’s filtered but not fined. The total sulfites are 20mg/L and all are added at bottling. My first tastes of it just after bottling were full of iodine (one of my favorite white wine aromas) and ripe lemon with a little wildness. It needs only a few minutes open to find its footing.

What is going on with Saumur Cabernet Franc? If it continues at its current upward trajectory, in ten, twenty years they will even further combine the noblest traits of Côte d’Or reds and left-bank Bordeaux, and will be the most balanced and beautiful red wines of France. Fréd’s whites are very good, but the red … Damn! This 2022 Saumur Rouge Puy-Notre-Dame, one of the most compelling and stunning wines I’ve had in 2024, is no accident, as that would be impossible. It’s only his second vintage, ever, but if I hit this level of mark on my second try, I’d be scared for the rest of my life that I’d never get close to it again. The constant heat spikes of the 2022 season made for some serious bullet-sized vigneron night sweats, but for Saumur reds in this moment of climate change, if one listens to nature and rides its wave the results can be this! Pick the right spot (hilltop tuffeau limestone and sandy loam), pick early and fresh with some sting still in ‘em and ripe enough to let the stems play their part, let only the right ones in the vat, guide don’t push, think more, react less, and when the time is right, lure it into the bottle at the peak of its powers. That’s what happened here.

This slightly turbid deep red rose-colored Saumur foreshadows the absurd pleasure of what’s to come. We’ve imported some gorgeous Saumur Cabernet Franc, but this kind of wine seems only possible from an outsider looking in; someone led by emotion and intuition that realizes (rather, doesn’t care to know) that at all times they are in the middle of a frozen lake during spring on the thinnest of ice. Fréd explained that even though he’s new to winemaking he doesn’t want the influence of more experienced winegrowers. Well, ok … it’s working. But what will you do next, Fréd? On this day in June, this wine has already led me to the tuffeau hilltop of my Cabernet Franc dreams, and there’s only one direction to go: further up. This wine won’t apex on a mountaintop; it will do so in the clouds above.

Planted in 1990 on an east-facing gentle hill of Turonian green chalk bedrock with a deep silt and sand topsoil, the grapes were 50% whole cluster and fermented/macerated with a single pumpover during its nine-day fermentation. It was then aged ten months in five to ten-year-old 228L French oak. It passes through malolactic fermentation and is neither filtered nor fined. 10mg/L total SO2 added only at bottling.

You will believe me when you try it.

And then there was Carole.

Sometimes you know instantly when you get lucky, again. Like my first Lambert wines from Brézé. Thierry Richoux’s 2006 Irancy with the Collets over dinner in Chablis. Veyder-Malberg’s first Wachau releases at his house in 2010. My first Dutraive in New York poured blind by my friend–a true sommelier, Eduardo Porto Carreiro. Cume do Avia’s 2017 red wines over lunch in Sanxenxo. Les Infiltrés’ 2021 Saumur Puy-Notre-Dame wines, a stunning first vintage from a complete rookie. My first two wines from Carole Kohler are part of this list.

When I first tasted Carole’s enchanted forest, biodynamic “Source” Chenin Blanc and “Jardin” Cabernet Franc, I thought, “These are too good.” I yelled to my wife from the kitchen, “It’s impossible that no one works with her in the US! … You won’t believe them. They’re crazy!”

We’re talking about the hottest category in France right now, especially for value, and they were complete insanity for an unknown—another Fréd! My tasting notes were filled with exhausted references to the great producers in every other sentence. I’ll spare you what would seem like hyperbole, but let’s just say that Carole’s wines are aligned with the world’s best raw wines. Name them. These are on par. Carole was our last visit before flying from Nantes back to Barcelona and it was as inspiring as I hoped.

On our call after drinking the wines for the first time, I tried to maintain a poker face—she always calls with video. I distracted her with inquiries of how she made them, about the vineyards (“slate, schist, silex and limestone all in three different plots only hundreds of meters away from one another? Really, all that in that small area?”), and finished with, “How much sulfur did you use?” “None,” she responded without explanation. Then she asked what I thought. I let her have it. “They’re just incredible … How are importers not swooning by the dozen? You never sent your wines to a US importer before me? Really? No sulfites, at all?”

Her 2022 Source and 2022 Jardin are spectacular. After my first set of two sample bottles, I bought three more of each from her, and my wife and I finished them in short order, then had another set in the company of Constantino Ramos, our talented grower and great friend in Vinho Verde. Each bottle was perfect, and the mystique of the unassuming and extremely humble Carole Kohler began to grow.

The walls tell the truth about the rocks in the ground: limestone, slate/schist, sandstone, silex—in one spot …

Three days before our first rendezvous with Carole, Arnaud Lambert asked who else we were planning to see, as he always does. I went through the list, but with Carole Kohler’s name, his eyes lit up, and he instantly corroborated all the fantastical stories about her wines. Arnaud is not one to charge into vouching for new growers, but there was no hesitation. He knows she’s special, but why didn’t he ever tell me about her?

I have no doubts about Carole Kohler and her magical forests and vineyards just outside of Thouars. Inside of the greater Anjou AOC, this long-time family home of her husband, Brice, is just 30 kilometers directly south of Brézé, the first place we struck the motherload. It’s also in the former Vins de Pays Thouarsais, an appellation discarded decades ago during the consolidation of EU regulations, along with most of the interest in this once-important wine region before phylloxera. There will be so much more on Carole to come, but I’m still digesting our visit and our opportunity to work with such a kind soul churning out extraordinary wines from an unexpected place.

There was another superstar we visited on our trip—one that will have to remain a secret, for now … I had my first bottle of his wine about two years ago and was told he had nothing to sell. It was true. This time he opened the door for us, but because his production is so small (though he is not) and won’t have wine for us until 2026 we will tuck this one away until the time is right. Bubbles. Incredible bubbles.

JD and I began our trip with a meeting in Barcelona before our flight to Catania, and it closed in the same city after a short one back from Nantes. I’ve dined at many of the recommended Barcelona spots, but too often they’ve fallen short. Gresca has been the most consistently good spot for me, even if this time it wasn’t the same level as the last half dozen times. While Gresca is a pretty sure bet, there’s now a new place that delivers perhaps the most personalized but casual service experience with a tapas family-style menu: Suru Bar is often described as a sort of “speakeasy,” but it’s right on the street with a sign in clear view. The list is well curated and the food is tight, clean, flavorful, and easier on the pocketbook than expected. The owners, not surprisingly offshoots of Gresca, are true hospitalitarians. It feels you’re in their direct care, and you are. It’s a must.