Co-authored and co-researched by MSc Geology and PhD Student at the University of Vigo, Ivan Rodriguez, and Ted Vance, from The Source Imports.

Preface

The geological setting of Navarra and Rioja can be distilled down to what is mostly sedimentary rock including limestones, marls, sandstones, and shales with a broad spectrum of different compositions, size grains (clay, silt, sand gravel, etc.), all formed under different conditions than those in the surrounding mountain ranges. This geological story is worth further exploration for anyone interested in northern Spain and southwest and southern France, and the mysterious and gorgeous Pyrenees mountains that stand between these countries.

Undoubtedly, surrounding reliefs (mountains and hills; the topography) of a specific place are the primary indicators as to the formation of the soils in that area. In this case, the mountain ranges of the Pyrenees and Sistema Ibérico (Ibérian Range) surrounding the subregions of Navarra and Rioja are the major contributors to the vineyard land in the southern portion of these areas.

Of special note is the composition of what has been inserted into certain depositions and whether they have calcareous origins. Many high-quality wines are produced in more calcareous environments, so it’s important to note if it’s present.

The Pyrenean Range

The Pyrenean Range includes the Cantabrian Range, which starts next to the northernmost subzone of the Iberian Massif, in the north coast of Galicia, where it rises from the ocean and runs east along the northern Atlantic Spanish coastline until it draws a natural barrier and border between France and Spain and ends at the Mediterranean Sea. Spanning around 800km (~500 miles) from east to west and 150km (~90 miles) from north to south, the geological history of this mountain chain originated with the Variscan and Alpine orogenies (mountain-building events). The Variscan orogeny (the unifying geological event that connected all the continents to form Pangaea; see our brief essay on Pangaea here) took place between 370-290 million years ago and its remnants make up the setting for many of today’s wine regions located on the Iberian Massif in western Spain and most of mainland Portugal; France’s Armorican Massif, Massif Central and most of Corsica; Italy’s Sardinia and parts of Calabria; Central Europe’s Bohemian Massif (think Riesling and Grüner Veltliner countries), and others. Nearly all of what is left of the Variscan Mountains is rooted in igneous rocks like granites or volcanic, and metamorphic formations such as slate, schist and gneiss.

After the Variscan orogeny (also known as the Hercynian), Pangaea started to break up, separating land masses and creating new continents, eventually leading to our current global environment. The once gigantic Variscan range may have stood as high as today’s Himalayas but lost thousands of feet to erosion over a two-hundred-million-year period. During that time, the Iberian Peninsula had two major elevated reliefs left from the Variscan range: the Iberian Massif, which covers the western side of Spain and almost all of mainland Portugal, and to the east the Ebro Massif, sandwiched between Catalonia and southernmost areas of France. The latter shares its name with the long, cone-shaped Ebro Basin opening toward the southeast, with its famous river, the 930km long Río Ebro that starts in Cantabrian mountains and flows southeast through Rioja and Navarra, eventually spilling into the Mediterranean just south of the Priorat and Montsant wine regions. Most remnants of the Ebro Massif are now covered by younger sediments down in the Ebro Basin, but in the Pyrenees, they are steep, rocky mountains referred to as the Axial Zone. These remnants are also present in Catalonian wine regions and France’s Roussillon (Banyuls and Collioure, among others).

The Alpine Orogeny and the formation of the Pyrenees and the Ebro Basin

The next stage of development of this landscape is due to the Alpine orogeny, which is still active today. The African and Indian tectonic plates continue their mashup as they head north, pressing against the Eurasian plate (today’s Europe and Asia), causing the formation of most of the higher peaks that can be found in Europe, North Africa, and Asia. These tectonic movements coupled with the formation of the Atlantic Ocean led to the opening of the Bay of Biscay, the large Atlantic section between Northern Spain and Western France. The underwater part of Northwest Spain (Galicia and Asturias) and Western France (Brittany and the western end of the Loire Valley) that were a single landmass during the Variscan Orogeny began to separate. Through this millions-of-years process, the Iberian Peninsula pivoted about thirty-five degrees in a counterclockwise direction. This produced convergence forces between the Iberian plate and the southwesternmost part of the Eurasian plate, and uplifted today’s Pyrenees. In France, this pivot set the stage for the development of France’s Aquitaine Basin, home to Bordeaux and many other wine regions, to cite one of many examples of its far-reaching influence on Western European wine regions.

The Alpine Orogeny is much more recent, and is related with the formation of the Alps and too many other mountain ranges to mention from Western Europe (only as far as Spain), Morocco, and through the Middle East to Asia, and even into Indonesia. Its name is not to imply that they are all considered part of the Alps mountain range, it’s that the Alpine Orogeny is the established geological time frame that includes all mountains on Earth that developed during this specific period.

After this second tectonic cycle there was a more relaxed period with few volcanic eruptions and earthquakes caused by tectonic movements. During these tens of millions of years, the higher parts of the mountain chain began their intense erosion (which of course is still happening today), while in the lower parts, those eroded sediments were deposited over tens of millions of years, forming younger nearby basins usually associated with big rivers and, consequently, a lot of wine regions: Spain’s Duero Basin, whose river, the Duero, is surrounded by vineyards for almost the entirety of its extensive run through Spain and Portugal, where the Portuguese call it, Douro; the Ebro Basin to the south of the Pyrenees, known in Spain as the Pirineos, among other Spanish dialects, and Pyrénées, in French; and the Aquitaine Basin in France, on the north side of the Pyrenees. More recently, during the ice ages (the last few million years) the erosion in the higher altitude areas began to carve out U-shaped valleys due to the action of glaciers.

While there can be found igneous and metamorphic rocks in the Eastern part of the Pyrenees and in some parts of the Cantabrian Range, the type of rock most present toward the south of the Pyrenees, in the depressions of the Basque-Cantabrian Basin (the northeastern most section of the greater Ebro Basin), home to the Navarra and Rioja, are largely of sedimentary origin, some marine sedimentation and other non-marine, continental rock depositions.

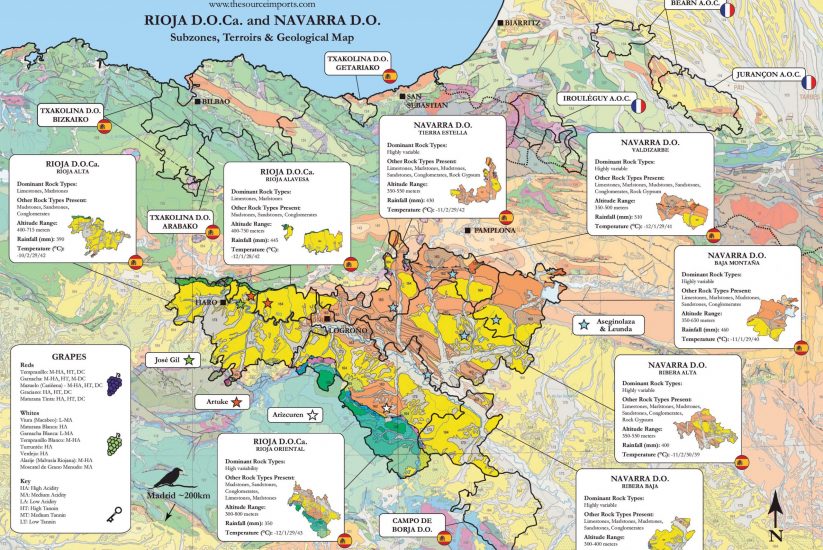

Navarra Overview

The geology of Navarra shows a great diversity in rock type as well as the age of their formation. Geologists divide this region into five geological units, and Navarra’s subregions are also five. To keep it clear, the Navarra’s DO subregions are in red and italicized.

Navarra’s largest geological zone is the Ebro Massif, which is connected with all of the Navarra DO subregions, but the Ribera Alta and Ribera Baja subregions are entirely within this geological unit. Here, the landscape is covered by a thick layer of young Cenozoic sediments. During the middle part of the Cenozoic (35 to 25 million years ago) a huge shallow lake was present over this area and extended from Rioja to the east through the Ebro Basin, which led to the formation of rocks, mainly mudstones, often rich in salt. Non-marine calcareous rocks are also present but in less proportion compared to Navarra’s vineyards further north. More recently, the activity of the Ebro River formed fluvial terraces along its course, with abundance of sand, silt, and clay originating from continental erosion with little influence from marine sediments, resulting in more rounded wines compared to those grown on more rocky soils further north.

On the eastern end of Navarra is the geological unit known as the Pyrenean Zone and also the northern part of Navarra’s Baja Montaña subregion. Prior to the Alpine Orogeny, this area was a tropical sea with different depths which developed an extensive variety of calcareous rocks formed by the calcium-carbonate skeletons of the organisms living in those environments, rocks like limestones, marls, sandy limestones, etc. Unique to this Navarra subregion are numerous valleys that run north-south, perpendicular to the Pyrenees.

The southernmost part of the geological unit connected to Navarra is called the Transition Zone and corresponds to the northern part of the Valdizarbe subregion. Here, characteristics from both the Pyrenean Zone and the Basque-Cantabrian Zone are present. The westernmost limit is in the Estella-Elizondo area, which gradually changes to the Pyrenean Zone towards the east. Like Baja Montaña, Valdizarbe has a great diversity of calcareous rock formations.

The northern part of Navarra’s western Tierra Estella subregion continues along the limestone Cantabrian Range where the Rioja subregion, Rioja Alavesa, ends. This area is what geologists refer to as the Basque-Cantabrian Zone (an extension of the Basque Arc/Basque Mountains). Geographically, it is the eastern part of the Cantabrian Range, but is also considered as the transition point with the Pyrenees. Like the Pyrenean Zone, it has a lot of calcareous sedimentary rocks, but these formations are not a dominant feature. The rocks here are from the Cretaceous and were developed in more continental environments, like deltas or estuaries, and shallow and sometimes deeper tropical sea areas.

(While the northernmost geological unit of this area, the Paleozoic Massif, has nothing to do with Navarra as an appellation, it’s worth noting that it is home to igneous and metamorphic rock types related to the Axial Zone.)

Rioja Overview

Rioja’s DOCa is geologically divided into three units: 1) the northwestern corner at the easternmost part of the Cantabrian Range; 2) The Iberian Range in the southern half of the region, formed by two mountain chains known as La Demanda and Cameros; and 3) the cone-shaped Ebro Basin that starts in the northern half and opens wider toward the southeast.

The Cantabrian Range connected to Rioja (the picturesque limestone mountain cliffs to the north) and the eastern part of the Iberian Range were uplifted during the Alpine Orogeny. Here we find marine sediments (limestones, etc.) as well as continental sediments (non-calcareous materials). This demonstrates the evidence of several different past environments, like shallow seas, deltas, estuaries, lakes, and rivers.

In the western part of the Iberian Range are the La Demanda Mountains, which act as a natural southern border of Rioja’s DOs, the oldest rocks of this region are found. Older than 350 million years, these Paleozoic metamorphic rocks were developed before the Variscan Orogeny and are mainly composed of schist, slate and quartzite, which contributed to many of today’s continental deposits of conglomerates and sandstones.

The Ebro Basin was formed by sedimentary rocks of continental origin from millions of years of sedimentation from the Iberian Massif and Ebro Massifs. Any existing calcareous rock formations (excluding recent calcareous depositions) were not formed under a marine environment but may have been caused by either biological origins (ancient deposits of tiny, calcareous skeletons of freshwater organisms) or by chemical origin in the form of evaporative concentration, or both, corresponding with lacustrine (lake) environments—similar to some tuffeau formations in France’s Loire Valley. However, calcareous marine sediments occur in the vineyards close to the Cantabrian and Iberian ranges in both Rioja and Navarra, due to the influence of these limestone mountains.

Unfortunately, the Rioja Alavesa subregion’s geological information is excluded from this map.

The Ebro Basin, where almost all of the vineyards of Rioja and Navarra are located, is a massive depression triangularly boxed in by the Pyrenean Range to the north (which technically includes the Cantabrian Range), the Iberian Range to the south/southwest, and the Catalan Coastal Range. The Ebro Basin’s sediments began to accumulate about 35 million years ago where a large lake developed. Likely between eight to thirteen million years ago, the constant deposit of continental, non-marine sediments in the bottom of the basin gave rise to this lake, eventually forcing it to breach the Catalan Coastal Range that blocked its access to the Mediterranean where it ultimately drained, and carved out a pathway to the Mediterranean for today’s Ebro River. In this basin, the sediments are as deep as 5km and make up most of the surrounding areas of Logroño, the capital of the department of La Rioja.

Rioja Subregions

Rioja’s subregions are located mainly within the geological unit of the Ebro Basin, with the exception of the south and southwestern parts of the Rioja Baja subregion, at the northern extreme of the Iberian Range. However, inside the Rioja DOCa areas there are two different reliefs (mountain areas, in this case) near many vineyards that are close enough to influence their soil composition. One is the southernmost Cantabrian Range (the Sierra Cantabria-Montes Obarenes), on the northern boundary of Rioja, in contact with vineyards from the Rioja Alavesa and the northernmost zones of Rioja Alta. Similar to Navarra’s northern subregions, this part of the Cantabrian Range is formed by diverse Cretaceous calcareous bedrock (limestones, sandy limestones, and calcareous sandstones) and sediments predominantly made of sandstones from the Utrillas Formation, one of the most spread out and well-known formations in Spain from the Cretaceous (110-95 million years ago); it’s formed predominantly by siliciclastic sandstones (non-calcareous) with a small proportion of mudstones and coal, deposited in a fluvial environment. However, more recent research suggests that these rocks are related to arid conditions, remnants of the dunes from a big desert that extended to central Spain.

The southeastern part of Rioja, in the Rioja Baja, some of the southernmost vineyards are in contact with the Cameros Mountains (the northernmost zone of the Iberian Range) and, contrary to its namesake, Baja, it has some of the highest altitude vineyards in Rioja. The lower parts correspond with Early Jurassic calcareous rocks: limestones, dolostones, muddy limestones, and marls. However, the low mountains of Sierra La Hez (including its arm up to Quel locality) and Yerga are a different story. These are the remnants of the southern margin of the lake covering the Ebro Basin before it found its path to the Mediterranean Sea. Here, it is formed predominantly by Paleogene conglomerates, sandstones, and red mudstones. However, if we go further south from there to Alhama Valley, we have the same rocks as in Cameros mountains and from a geological perspective it could be considered part of Cameros. The higher parts of these mountains are formed by a mixture of Cretaceous conglomerates, sandstones, mudstones and, in less proportion, calcareous rocks, including marls and limestones. The more southerly parts on the south face of these small ranges are Early-Middle Jurassic calcareous rocks: limestones, dolostones, muddy limestones, and marls; for example, the formations between Yerga Sierra Range and the town of Grávalos. However there are exceptions, for instance, the area around Igea corresponds with the non-marine, Cretaceous continental rocks.

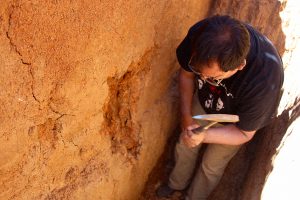

The soils in the Rioja DOCa have been intensively studied over the last decades, highlighting the average characteristics of the vineyard soils as poor in organic matter (less than 1%), alkaline pH (higher than 8), with an average total carbonate content of 20% and a texture type of soil corresponding to loam (sand: 41%; silt: 38%; clay: 21%) according to studies from the University and the Government of La Rioja (Peregrina et al., 2010; Iñigo et al., 2021). In the Rioja Region, inceptisols, entisols, aridisols and alfisols are present (USDA soil taxonomy); however, a more simplified classification of the soil by Ruiz-Hernandez (1974) divides them into three main types, including a map of their distribution: 1) Calcareous-clay soils with a yellowish color, composed of sandstones, marls, and a variable component of clay which are found mostly in Rioja Alavesa and the nearby Rioja Alta zones; 2) Ferruginous-clays with a red/orange color, composed of clay, sandstone, marl, and limonite, a mix of iron-bearing minerals which give it its ferruginous characteristic (Fe, as in the atomic symbol for iron), are found mostly in Rioja Alta and Rioja Baja; 3) Alluvial soil formed by the river sediments from the Demanda mountains that are present in most of the valley.

Rioja has many freestanding hills inside the Ebro Basin referred to as cerros, like the picturesque hilltops of the historical villages of San Vicente de la Sonsierra and Laguardia. These hills, along with the region's many fluvial terraces (a result of processes associated with the activity of rivers and streams). These terraces are also an important geological formation when considering the objective of a winegrower, whether it is for quality or quantity. Terraces at higher altitudes have more sandstones and calcareous materials present, while the lower areas generally have a deeper topsoil with more detritic (non-calcareous) depositions. Throughout Rioja, cerros extend along the Ebro Basin and were formed once the massive lake began to spill into the Mediterranean, followed by continued erosion by rivers and streams. Areas with harder rock gave greater resistance to the erosion, allowing these hills to stand alone. Clays and small grain-sized sandstones are easier to erode when compared with harder limestones located at higher altitudes.

Regarding the carbonate content of these soils—a seemingly ineffable asset often involved with high quality wine, Ruiz-Hernandez says that the calcareous-clay soils possess more than 25% of total calcium carbonate content while the others are far less rich in this mineral. More recently, Iñigo et al (2021), made a soil spatial variability of several components of the soil, measuring levels of total carbonate of up to 54% on the subsoil in the Rioja Alavesa, the highest overall among the subregions, but obviously similar to vineyards in Rioja Alta with close proximity to the limestone Cantabrian Range.

These maps demonstrate the general soil structure of Rioja, which unfortunately excludes Navarra.

Rioja and Navarra Comparison: Where the limestone ends…

Many of the vineyards from Rioja Alavesa and northern Rioja Alta are in direct contact with, or nearby (less than 5 km), the Cantabrian Range, which was formed by a succession of calcareous and siliciclastic formations during the Cretaceous. These sections, with township names added to give a general range of the location for these formations, could be divided from west to east: 1) Foncea-Cellorigo: limestones and dolostones; 2) Cellorigo-Villalba de Rioja: Utrillas Formation (sands, conglomerates and sandstones); 3) Ermita de San Felices-Briñas: alternation of Utrillas Formation with limestones, sandy limestones, and dolostones; 4) Labastida: conglomerates, sandstones and red clays with a very low calcium carbonate content (less than 13% according to Iñigo et al., 2021); 5) Eastern Labastida-Rivas de Tereso: limestones and dolostones, with the exception of Peña Colorada where the Utrillas Formation is present; 6) Leza-Kripán: Conglomerates with scarce outcrops of limestones and dolostones; 7) Kripán-Lapoblación: limestones, sandy limestones and dolostones; 8) Lapoblación-Estella: conglomerates, sandstones and red clays with a surprisingly high carbonate content (see details below); 9) Estella-Abarzuza: marlstones, limestones and calcareous sandstones; and 10) Abarzuza-Pamplona: predominantly calcareous sandstones and marls, but also limestones (less calcareous than in Estella-Abarzuza).

Iñigo et al. (2021) compared calcareous/non-calcareous sections to the total carbonate content in soil within the Rioja Alavesa and northern Rioja Alta, and there seemed to be consistent variations of carbonates. However, small variations might be not represented in the publication by Iñigo et al, due to the area sampling size. There are also anomalies around every corner; for example, the eastern sections of Rioja around Lapoblación (a largely non-calcareous region) there is a notable spike in carbonate levels, which raises the question of the origin of these carbonates as there may have been a more complex system of sediment transport within the triangle of Laguardia-Logroño-Viana.

Concluding notes, as of now:

Rioja and Navarra share more geographical and geological similarities than differences, and the same applies to their histories and cultures, which we have left to other essays. When considering the quality of a terroir, it is always most important to consider each one for its own unique characteristics, rather than lumping them in with a region’s collective categorization.

Acknowledgements:

We want to thank Dr. Fernando Peregrina, researcher from the University of La Rioja, for taking time to make numerous useful suggestions that improved this essay.

References:

Agirrezabala, L.M., Alonso, J.L., Anglada, E., Aranburu, A., Arranz, E., Aurell, M., […] and Villas, E. (2004). La Cordillera Pirenaica. In Geología de España. IGME, Madrid.

Barnolas, A. and Pujalte, V. (2004). La Cordillera Pirenaica: Definición, límites y división. In Geología de España. IGME, Madrid.

Bellido, N. P., and Cristóbal, A. C. (1995). Distribución espacial del viñedo de Rioja en relación con los condicionantes ambientales. Berceo, (129), 75-95.

Caja Navarra (1990). Gran Enciclopedia de Navarra: Geología. http://www.enciclopedianavarra.com/?page_id=10472 [Checked on 01/10/2022]

Castiella, J., Solé, J., Villalobos, L. (1977). Mapa geológico y memoria de la Hoja nº 243 (Calahorra). Mapa Geológico de España E. 1:50.000 (MAGNA), Segunda Serie, Primera edición. IGME, 27 pp.

Choukroune, P. (1992). Tectonic evolution of the Pyrenees. Annual Review of Earth andPlanetary Sciences, 20(1), 143-158.

Consejería de Turismo, Medio Ambiente y Política Territorial de La Rioja (2005). Mapa geológico de la Comunidad Autónoma de La Rioja a escala 1:200.000. https://www.larioja.org/industria-energia/es/minas/jornadas-estudios-publicaciones-tecnicas/elaboracion-mapa-geologico-rioja

Durantez, O., Sole, J., Castiella, J., Villalobos, L. (1982). Mapa geológico y memoria de la Hoja nº 281 (Cervera del Rio Alhama). Mapa Geológico de España E. 1:50.000 (MAGNA), Segunda Serie, Primera edición. IGME, 41 pp.

Gong, Z., Langereis, C. G., and Mullender, T. A. T. (2008). The rotation of Iberia during the Aptian and the opening of the Bay of Biscay. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 273(1-2), 80-93.

Iñigo, V., Marín, Á., Andrades, M. S., & Jiménez-Ballesta, R. (2021). Soil spatial variability in the vineyards of La Rioja PDOC (Spain). International Journal of Environmental Studies, 1-11.

Peregrina, F., López, D., Zaballa, O., Villar, M. T., González, G., & García-Escudero, E. (2010). Calidad de los suelos de viñedo en la Denominación de Origen Rioja: Índice de riesgo de encostramiento (FAO-PNUMA), contenido de carbono orgánico y relación con la fertilidad del suelo. Revista de Ciências Agrárias, 33(1), 338-345.

Portero-García, J.M., Ramírez del Pozo, J., Aguilar-Tomás, M. J. (1978). Mapa geológico y Memoria de la Hoja nº 169 (Casalarreina). Mapa Geológico de España E. 1:50.000 (MAGNA), Segunda Serie, Primera edición. IGME, 41 pp.

Portero-García, J.M., Ramírez del Pozo, J., Aguilar-Tomás, M. J. (1979). Mapa geológico y Memoria de la Hoja nº 170 (Haro). Mapa Geológico de España E. 1:50.000 (MAGNA), Segunda Serie, Primera edición. IGME, 43 pp.

Ruiz-Hernández, M. (1974). Estudio de la trascendencia vitivinícola de los diversos perfiles de suelos en Rioja. La Semana Vitivinícola 1453/1974, 80-90.

Sibuet, J. C., Srivastava, S. P., and Spakman, W. (2004). Pyrenean orogeny and plate kinematics. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 109(B8).

Vergés, J., Kullberg, J. C., Casas-Sainz, A., de Vicente, G., Duarte, L. V., Fernández, M., [...] and Vegas, R. (2019). An introduction to the Alpine cycle in Iberia. In The geology of Iberia: a geodynamic approach. Springer, Cham.